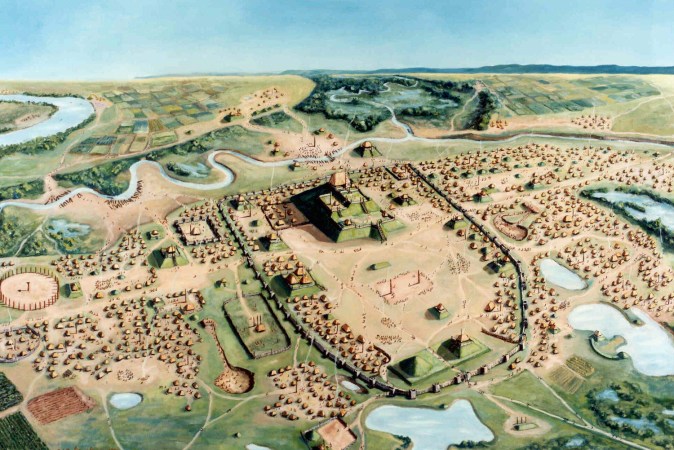

Just a river’s crossing away from St. Louis, Missouri, rests an ancient and mysterious anthropological site that few Americans know of. Scholars still discuss the potential reasons for the demise of Cahokia, a massive settlement that may have housed as many as 20,000 people by 1050 A.D. The metropolis, which sits in the fertile floodplain of the Mississippi River Valley that’s now western Illinois, was made up of towering, handmade earthen mounds, the largest of which still exists at the Cahokia Mounds State Historic Site. While there are a lot of unknowns when it comes to this ancient civilization, including why it disappeared, remains have helped researchers paint a picture of what the city was like at its peak.

Ancient teeth at this site hint that it was home to a diverse group of Indigenous people. Roughly a third of the population came to Cahokia from other areas in middle America, based on the varying strontium levels in the dental fragments. The architecture is telling too: The organization of the mounds in Cahokia leads archeologists to believe this city had some level of urban planning, and was not just a collection of villages. Rulers lived on top of mounds, looking down at the structures other inhabitants lived in. Farming, hunting, logging, pottery, and weaving were all conducted inside this massive city.

[Related: The famous Nazca lines aren’t mysterious—but they are ingenious]

In the center of Cahokia, surrounding the biggest mound of roughly 100 feet tall, sat the city center, encircled by a massive wooden palisade. The area held a plaza that archeologists believe was inspired by the creators concept of the cosmos at the time, with the four corners marking the cardinal directions. Researchers believe this town center, and the buildings on top of the central mound, were actually where religious ceremonies and events took place. It’s even possible that people traveled from outside of Cahokia just to attend these gatherings.

As for why Cahokia fell, a few theories have come into play, but with conflicting evidence. For a while, it was believed that the residents’ dependence on wood for their structures led to over deforestation of the land, which ultimately made it less fertile. But soil samples show that the land would still have been fertile shortly after the fall of Cahokia. Colonists did not reach this space until much later, making disease an unlikely calamity as well. Other experts believe that fighting with neighboring groups may have caused Cahokia’s fall.

Today, the mounds comprise a city park and state historic site, but are in consideration for a national park designation. Visitors can climb the steps of the highest mound still standing at Cahokia, among more than 65 other preserved mounds. It’s one of the few places in the US where people can freely walk through a millennia-old metropolis.