No one eats two Oreos. Either you eat none or you eat a dozen—there is no in between. But until recently, the Food & Drug Administration only required food labels to display the nutritional content for one serving. So, Nabisco informed consumers that their cookie snack only contained a paltry 140 calories.

The same goes for most other junk food. If you buy a 20 ounce bottle of soda, you’ll likely finish it, rather than not stop at 12 ounces and decide that’s about enough sugar for the day. In 2016, the FDA finally came to their senses and decided that food labels must match with the quantities that Americans actually consume. No more hiding the true sugar content of that Coke with a smaller serving size.

Food companies have been rolling out the new nutrition labels over the past few months, but last week, the FDA made clear exactly why those changes were made, along with some non-serving-size related updates about the new tags. Some of it is about legibility, but much of it is about staying up-to-date on what the best science says about maintaining a healthy diet. All of it is intended to help Americans make better choices. It also remains to be seen what effect the changes will have on our nation’s process food-heavy diet; it might also be the best shot we have.

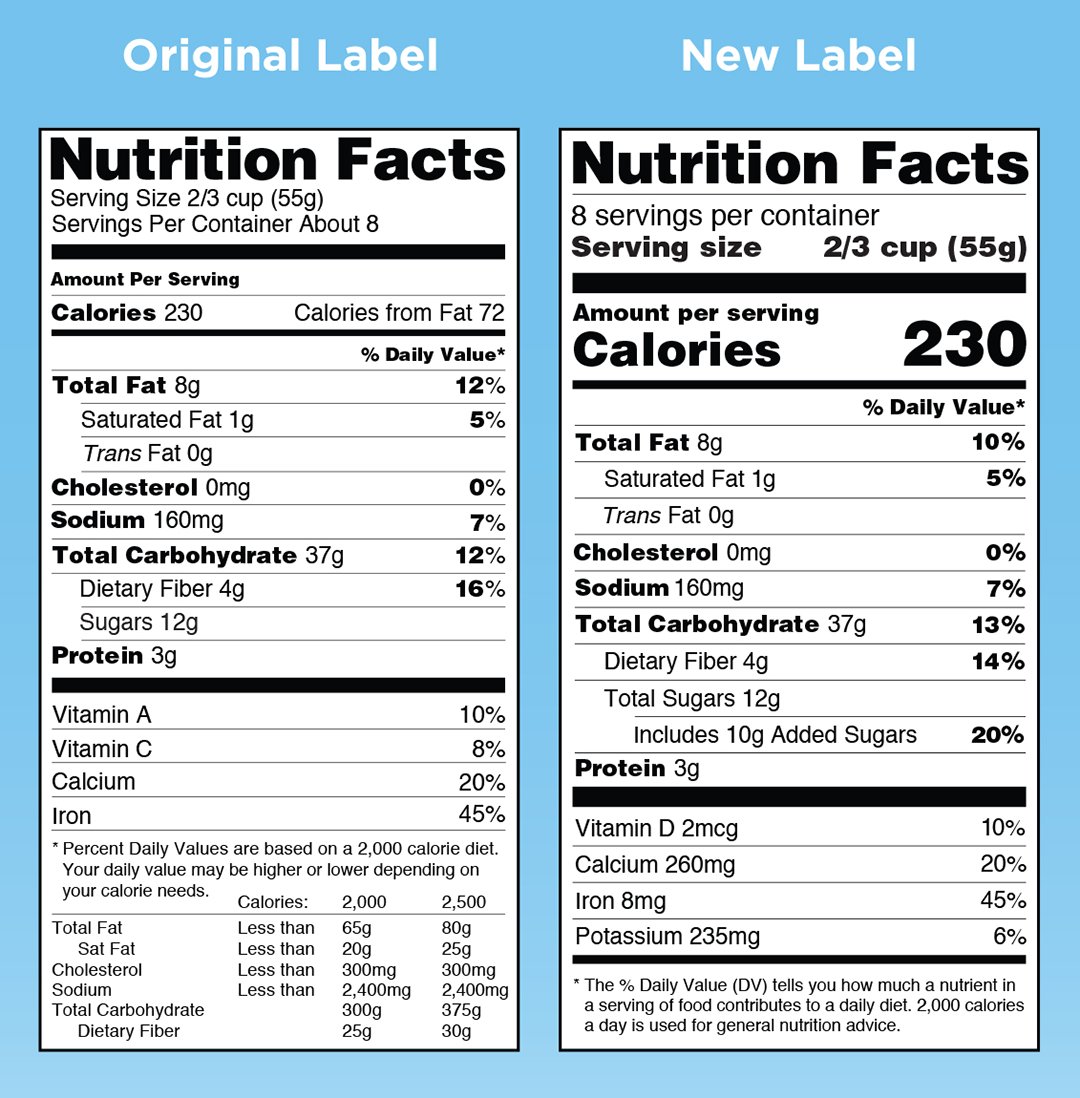

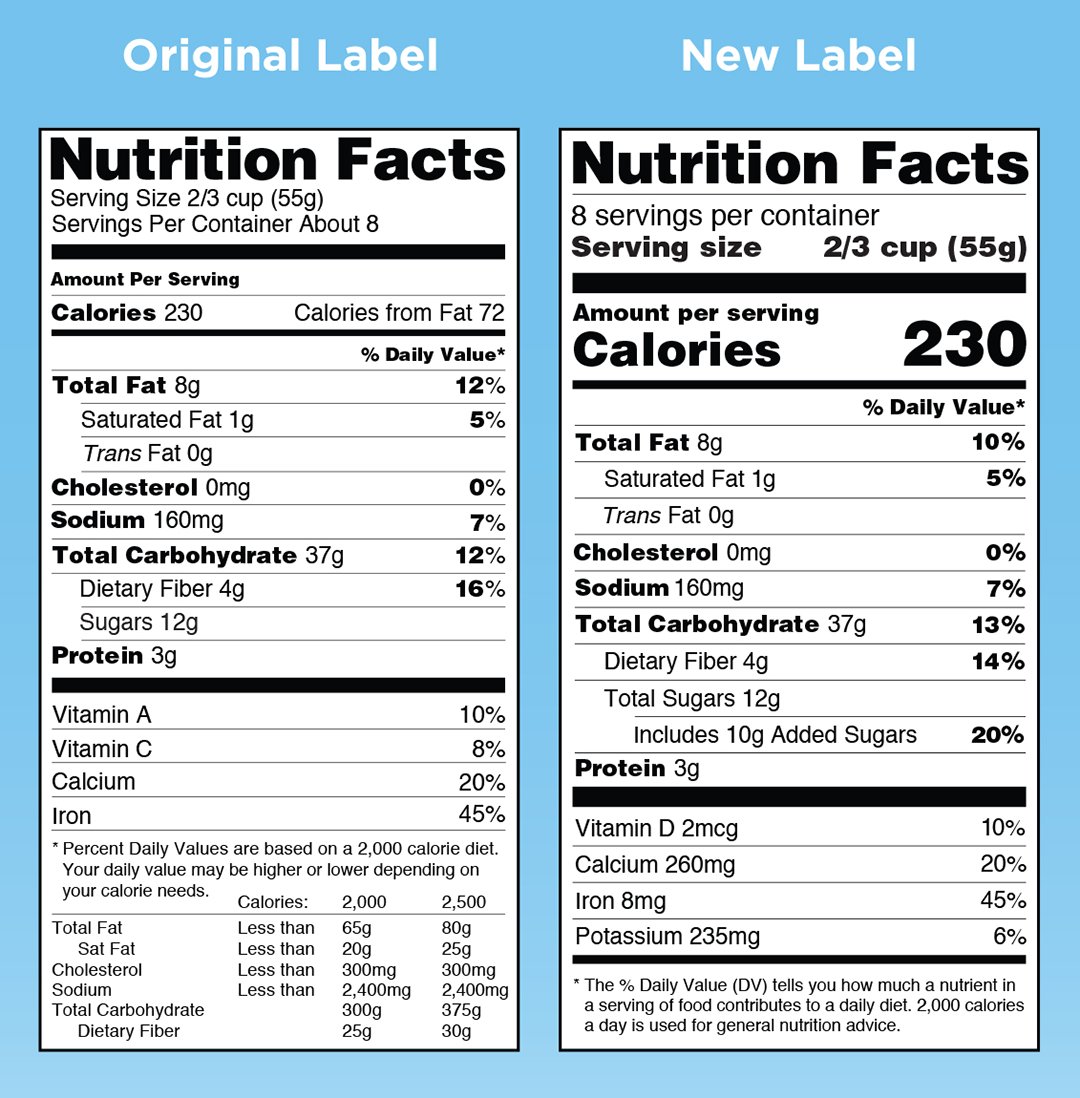

New to the label: added sugars, bigger numbers, better vitamins

As we’ve reported before, added sugars are one of the biggest changes to the labels. As of this summer, the FDA requires food manufacturers to list both total sugars and the grams of added sugars, which are those that don’t naturally occur in the product. Apple juice, for instance, may contain plenty of natural sugars that don’t have to be listed separately, but if the manufacturer adds in some corn syrup that has to be noted on another line.

The idea here is that, in general, additional sugar affects the way the body processes and stores nutrients and calories. This can ultimately lead to obesity and type 2 diabetes. There are caveats to this. Juices, for example, contain only natural sugar, but nutritionists agree that juicing a fruit eliminates the fibrous flesh that helps our bodies digest those sugars properly. If you’re not eating the whole thing, those natural sugars may as well have been added. And maple syrup, though a wholly natural product, is almost entirely sugar.

Along with the added sugars line, the FDA has also opted to focus more on the total calorie count of a product. Small packages will list the calories for the entire package, while larger ones will note calories per serving size (updated to reflect the growing American portion size) along with the total calories per container. The larger font helps that number stand out from the black-and-white mess that is a standard nutrition label.

Finally, the vitamins listed at the bottom have shifted slightly. The old labels displayed percent daily values for iron, calcium, vitamin A, and vitamin C. Calcium and iron are sticking around, but the FDA has swapped out the two others and replaced them with vitamin D and potassium. Research showed that Americans rarely have vitamin A or C deficiencies anymore, but now can have low vitamin D and potassium levels.

Going away: calories from fat

Alongside vitamin A and C, the FDA has decided to eliminate the long-standing calories from fat item. In its own words, this is because “research shows the type of fat consumed is more important than total fats.” Saturated and trans fats, unlike the healthy mono- and polyunsaturated versions found in nuts and vegetable oils, are the ones that negatively affect your health, so the FDA is focusing on those instead.

It’s worth noting, though, that trans fats are far worse for you than saturated fats. Trans fats are what you get when you add hydrogen atoms to a normally unsaturated fat molecule (the “unsaturated” part means they have less than the maximum possible number of hydrogen atoms on their long tails). They’re now banned in multiple countries, the U.S. included, because of their known severely negative effect on heart health. Saturated fats have a more murky outlook. They’re not good for you, and eating lots of them can shift your blood lipids levels towards the unhealthy end of the LDL (bad cholesterol)/HDL (good cholesterol) balance. But as Harvard Health points out, recent studies suggest that although “replacing saturated fat with polyunsaturated fats like vegetable oils or high-fiber carbohydrates is the best bet for reducing the risk of heart disease,” it’s also true that “replacing saturated fat with highly processed carbohydrates could do the opposite.”

The big question: Will it help?

Since the 1990s, when the FDA first started regulating food labels, there have been plenty of studies on the influence these nutrition tags have on American’s health. Both individual ones, as well as meta-analyses, show a correlation between reading nutrition labels and having a healthy diet. Some researchers think that this is probably a bi-directional correlation, meaning that both factors have an influence on one another. As one 2010 meta-analysis put it, “nutrition labels may promote healthier eating, whereas individuals with healthier diets are more likely to seek out nutritional labels in the first place.” That same analysis concludes that “there is sufficient evidence from a range of study designs to conclude that providing nutrition information on packages has a positive impact on diet.”

But not all scientists are so convinced. A paper from the same year appearing in the Journal of the American Dietetic Association found that only 61.6 percent of Americans even look a the nutrition panel. The authors concluded that “label use alone is not expected to be sufficient in modifying behavior ultimately leading to improved health outcomes.” In order for the labels to do that, the authors wrote, more people would have to read the labels in the first place. They (and others) also suggest a number of label changes that research suggests might encourage more people to read and understand the nutritional value of their food, including printing the calorie counts in bold font and reporting more realistic portion sizes—both of which the FDA are doing.

As for whether it’ll actually help, we’ll just have to wait and see. When fast food restaurants started reporting calorie counts on their menus, everyone hoped that it would encourage people to eat less. But research since then suggests it’s had very little impact on the population as a whole. One meta-analysis noted, however, that certain subgroups—especially people primed to pay attention to their diet—did have a significant change in their diet in response to the calorie labels. Maybe you’re one of those people. Nutrition labels may have a difficult time getting 350 million people to shift their diets, but if you decide you’re going to start paying attention, think of the positive impact you could have on your own life. All it takes is turning that package around and reading the label. It’s now easier than ever.