If the paranoid blogosphere is to be believed, every morning a group of plasma-physics grad students wakes up at a research facility in Gakona, Alaska, 200 miles north of Anchorage, and prepares for another day of playing God. It’s cold, dark as a mineshaft in winter, and the day’s work does little to cheer the mood. Depending on the unpredictable agendas of military scientists, this group of technicians must shoot radio waves into the upper reaches of our atmosphere to create missile shields, eviscerate enemy satellites, set off the occasional earthquake, or control the minds of millions of people.

The truth is, though, that the High-frequency Active Auroral Research Program, or HAARP—the 180-antenna array that became fully operational last year when the defense-systems contractor BAE finished installing transmitters—is nothing more sinister than a research station. And now, 15 years after construction on the station began, HAARP’s managers are seeing what the fully powered system can do; most recently, they’ve begun zapping the moon with the hope of determining the composition of its soil. “It’s up, it runs, it performs beautifully,” says Ed Kennedy, the former HAARP program manager for the Naval Research Lab. “HAARP is a great example of a project that from start to finish stayed on schedule and on budget.”

HAARP’s purpose is to study the ionosphere (the section of the atmosphere beginning about 50 miles up in which ultraviolet radiation temporarily strips atoms of their electrons), the magnetosphere (the region in space above the ionosphere where the Earth’s magnetic field affects the behavior of charged particles) and the Van Allen radiation belts (bands of highly charged particles contained in the magnetosphere beginning some 400 miles up). Scientists are interested in the ionosphere because of its ability to affect radio signals; the Van Allen belt, because the radiation there damages satellites, and a better understanding of it could lead to ways to make satellites last longer. “It’s an open plasma-physics laboratory,” says Dennis Papadopoulos, a physics professor at the University of Maryland who helped conceive the idea for HAARP with the Naval Research Lab more than 30 years ago. “You test ideas and scientific theories. Then, if something’s important to the Department of Defense, you apply it.”

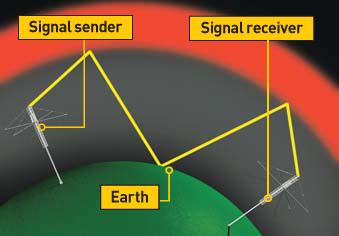

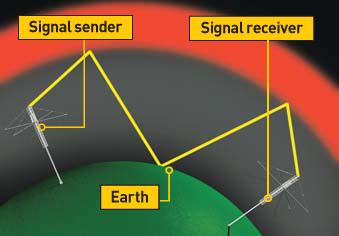

One application government scientists are particularly interested in is turning the lower ionosphere into a tool for broadcasting radio signals or bouncing them around the curvature of the Earth. By beaming a signal ranging from 2.8 to 10 megahertz into the ionosphere and then pulsing the signal, HAARP stimulates what’s called a “virtual antenna”—a radio interaction that causes the ionosphere to send a very low-frequency signal back down to Earth. The phenomenon could theoretically improve submarine communication. Because salty, conductive seawater absorbs high-frequency radio waves, submarines currently operate with wires that reach up into shallow depths to receive usable radio signals. Low-frequency signals like the ones HAARP generates in the ionosphere could allow subs to operate at much deeper depths. “It’s a real signal that comes from space as though there were an antenna up there,” says Paul Kossey, HAARP program manager for the Air Force Research Laboratory’s Space Vehicles Directorate. “But there’s no wire doing it.”

Of course, a vocal minority of HAARP-watchers have their own ideas about the purpose of the $230-million, taxpayer-funded antenna array. For many years, HAARP’s most prominent critic was Bernard Eastlund, a plasma physicist who reportedly worked for the Strategic Defense Initiative (Star Wars) and, later, Advanced Power Technologies Incorporated, the company originally tasked with building HAARP. Eastlund, who some believe was dismissed from the company for his extreme ideas, claimed that HAARP was built with his patents—patents for technologies that could be used to modify weather and disable satellites.

Since Eastlund’s death last December, Nick Begich, son of a former Alaskan congressman and co-author of the 1995 book Angels Don’t Play This HAARP: Advances in Tesla Technology, has led the anti-HAARP crusade. “It’s not that I think it needs to be shut down,” Begich says. “It needs to be monitored more closely and scrutinized. The government hasn’t been up-front about the nature of these programs, and they’re utilizing the system to manipulate portions of the environment without full disclosure to the public.” He worries that HAARP may be capable of mind control because the waves it produces can exist at frequencies similar to those of human brain waves. Citing Eastlund’s patents, Begich also worries that the facility can alter weather. More extreme skeptics, like Jerry E. Smith, author of HAARP: The Ultimate Weapon of the Conspiracy, suspect that HAARP was rushed into completion after the 2005 hurricane season, which included Katrina, to keep the storms from making landfall. Others say it was responsible for the destruction of the space shuttle Columbia in 2003.

Ask a HAARP scientist about allegations like this, and he’ll either laugh or lose his temper. “This is completely uninformed,” says Umran Inan, a professor of electrical engineering at Stanford University whose research group works with HAARP. “There’s absolutely nothing we can do to disturb the Earth’s [weather] systems. Even though the power HAARP radiates is very large, it’s minuscule compared with the power of a lightning flash—and there are 50 to 100 lightning flashes every second. HAARP’s intensity is very small.”

“You hear these people talking about mind control, and it’s just not serious,” Papadopoulos says. So we don’t need tinfoil hats to prevent evil government scientists from controlling our every thought? “We have difficulty measuring the signal. We do experiments all the time up there, and we don’t wear hats.”

**Conspiracy or not? Launch our gallery here to see the great debunking.

Abe Streep is an associate editor at Outside magazine.