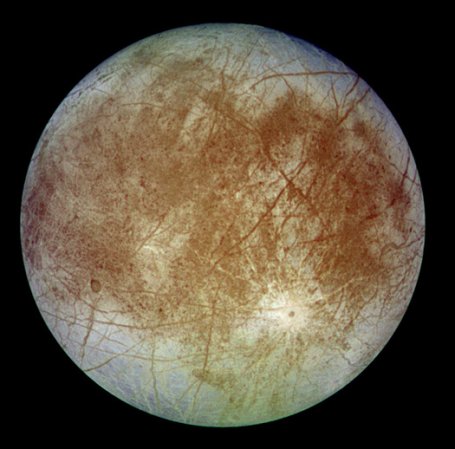

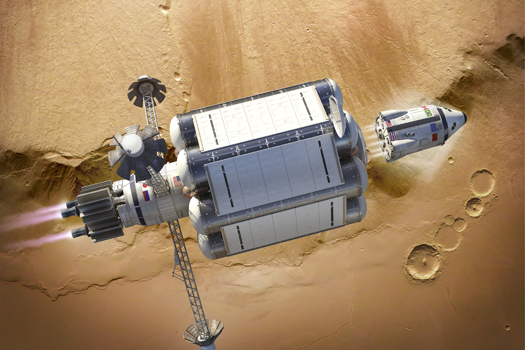

NASA hopes to someday use a robot like Bill Stone’s DepthX to explore Europa, a frozen moon of Jupiter and one of the most probably places in our solar system to support life. For a look at how such a mission might be carried out, launch the photo gallery.

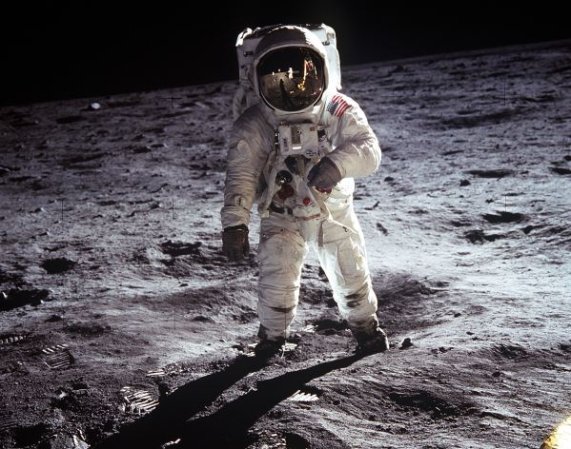

When it is dark, cold and wet, when he is in a cave 4,000 feet below the surface of the Earth, when rock envelops him in a world devoid of life or color, Bill Stone dreams of space. He sees the icy expanses of Jupiter´s moon Europa, furrowed with ridges. He pictures the broad red dome of Olympus Mons, the highest mountain in the solar system, rising above a rocky Martian plain. And he sees himself: Driving a rover up from the tar-black depths of a lunar crater, cresting a rocky rim bathed in light.

Bill Stone is not an astronaut-he is the world´s most famous expeditionary caver. Leading large international teams and backed by sponsors like the National Geographic Society, he has mounted more than 50 major expeditions to plumb the most hostile reaches of inner space. Spending weeks underground, his crews have traveled deep inside the planet to the remotest locations touched by humans. Nobody is better at what he does, but this gives him limited satisfaction. For Stone, caves are a proving ground. He is consumed by ideas for how humanity could explore and colonize space and wants to personally establish a privately funded base on the moon. It is, he thinks, nothing less than destiny.

A reasonable observer might choose another word: obsession. Delusion. Fantasy. Stone possesses neither great wealth nor extensive political connections. He is an engineer and runs Stone Aerospace, a company so small that when FedEx rings, he usually signs for the package himself. So to hear Stone talk-“It´s not a quantum leap for me to go to the moon; it´s just a lateral transgression”-the conclusion seems sadly obvious. He´s nuts.

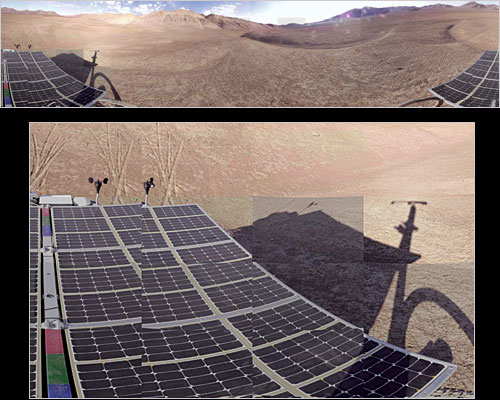

But now, after spending nearly three decades on the margins of the space industry, Stone is closer than he´s ever been to proving that caves are the best earthly training ground for exploring space. Backed by a $5-million grant from NASA, he is developing a robot called DepthX that may turn out to be the most advanced autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) ever. Like its inventor, DepthX is a caver, capable of navigating constrained, obstacle-filled environments. Its theoretical mission, though, is bold even by Stone´s standards: a hunt for extraterrestrial life on the Jovian moon of Europa.

DepthX´s first major field trial will take place this month in Mexico´s Zacatn Cenote, the world´s deepest sinkhole. For Stone´s future space ambitions to have any chance, he needs to impress the new generation of wealthy space-crazed investors. To do that, he needs to ace this high-profile audition and, at 54 years old, he needs to do it fast. As one of his oldest friends puts it, “Time is running out for Bill.”

A Giant Orange Eyeball

Some 575 million miles from Europa, on the back lot of a secure government testing facility in Austin, Texas, a round robot floats in the center of a test tank like an orange bobbing in a giant pot of holiday grog. On a platform beside the tank is a metal-sided trailer office, the kind you´d find on a construction site. A man´s voice comes from inside. “It´s time,” he says. The robo-orange, which is about seven feet across, rotates neatly in place, expels air with a bubbling hiss like a breaching whale, and drops below the surface.

It´s late October, and I´ve come to Austin´s Applied Research Laboratories (ARL) to watch one of the final days of tank testing before DepthX is deployed at Zacatn. Inside the metal trailer are several members of the DepthX team. There´s John Kerr, the lab manager of Stone Aerospace, which specializes in autonomous vehicles, life-support equipment, and laser and sonar imaging devices. Kerr is joined by George Kantor and Dominic Jonak, roboticists from Carnegie Mellon University, and John Spear, a biologist from the University of Colorado. The gang´s demeanor is low-key, but there´s an undercurrent of tension. If DepthX goes awry, it could damage both itself and the multimillion-dollar test tank. If the test goes well, the team will be one step closer to a landmark achievement in autonomous robotics.

To understand the audacity of what Stone is attempting, consider the capabilities of Spirit and Opportunity, the semi-autonomous rovers currently exploring the surface of Mars. Though hugely successful at gathering data and imagery, the rovers are essentially highly sophisticated remote-control cars; they receive marching orders from human mission controllers whose decisions are informed by pictures of the terrain around the robots. The ultimate goal for DepthX, meanwhile, is to be fully autonomous. Alone in an unknown environment, it will have to figure out where it is, where to go and what to do.

Inside the trailer, Kantor scans a computer that´s monitoring the robot´s performance, while Kerr stands outside watching DepthX. The robot´s navigation systems are being tested, and it slowly traces the outline of a square at a depth of about 10 feet. The maneuver looks precise, but apparently it wasn´t perfect. “It overshot the corner of its box,” Kantor says, squinting at lines of code.

DepthX, at its most basic level, is a giant eyeball. Ringed with 54 sonar sensors, it collects data from thousands of sonar hits every minute to build what Stone calls “a hugely dense picture” of the environment around it. The robot not only charts a three-dimensional map of the world but also knows its place within it, using an inertial guidance unit, accelerometer, depth gauge and other sensors to pinpoint position. Together, these capabilities are known as Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM).

“This is the first instance of full 3-D SLAM underwater,” Kantor says. In fact, it may be the first instance of full 3-D SLAM in any environment. Existing autonomous vehicles-the driverless SUVs in the Darpa Grand Challenge, for instance-have a relatively narrow, forward-looking field of vision because that´s all they need. As a caving robot, though, DepthX might encounter obstacles in any direction, so it must be all-seeing as well.

The robot´s predecessor was a device Stone invented called the Wakulla Springs Mapper, which was mounted on the tip of a torpedo-shaped propulsion unit and piloted by a scuba diver. In the late 1990s he used the craft to chart several thousand feet of passages in Wakulla Springs, Florida, creating the world´s first digitally generated, three-dimensional cave map. DepthX is far more complex than the device that inspired it-not least because it must function independently at a depth of 1,000 feet or more at Zacatn-but the fundamental concept remains the same.

“In theory, theory and practice are the same, but in practice, they´re not,” says John Rummel, the NASA astrobiologist who is overseeing Stone´s work. “Bill clearly has a lot of practical experience with cave environments that came to fruition in the design of DepthX.”

The Right Stuff?

Stone has always wanted to go to space. Growing up, he was enthralled by John Glenn´s historic first orbital mission of Earth in 1962. “From that point on, I focused on becoming an astronaut,” he says. “I was motivated to get a Ph.D. [in structural engineering] by that ambition. I built a rsum that included learning to fly with the goal of getting into space.” In 1989 Stone got what looked like a big break. He was one of 60 finalists, chosen from a pool of 10,000 applicants, who were summoned to NASA headquarters to try out for the Astronaut Corps.

In Stone´s recollection, he aced a battery of physical, mental and emotional tests (20/50 vision in one eye was the only significant strike against him), and after several days, he was called into a conference room for a critical interview before a panel of senior astronauts. After several easy questions from the group, a space-shuttle veteran named Guy Bluford asked Stone if he had any regrets in life. He said he had none. Bluford asked again. Silence is not Stone´s strong suit-his personality is essentially that of an eight-year-old with attention-deficit disorder-and this time he said, “My financial status. I need about $2 billion.” “What would you do with that?” Bluford asked incredulously. “I´d land a private exploration team on the moon,” Stone replied.

Over the past decade, Stone had made himself into a space savant. His day job was as an automation expert at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, but in his spare time he published scientific papers on life support, rocket propulsion and spacecraft design. His technical genius and space fervor became known, and in 1982 he was selected for a congressional panel that reviewed existing space-station plans and, later, for another federal panel that spent five years developing one of its own.

Still, no matter how much Stone thought he knew, his comment before the astronaut panel showed arrogance and a lack of restraint, and it didn´t go over well. “Son, within your prospective tenure as an astronaut, it is highly unlikely that NASA will return to the moon,” growled Don Puddy, a revered flight director at Johnson Space Center.

“It was like somebody taking a pin and sticking it right into that little balloon of hope that I had been growing for all of those years,” Stone recently recalled. “It was like, “Dudes, if you´re not interested in exploration, then what the hell are you doing up there?´ ” Stone was sent home. And that, he says, was OK. The space agency´s exploration component was “gutless,” he decided, and he had other ideas. With a little help from others at NASA-he still greatly respected the agency´s scientists-and a lot of work on his own, he would find other ways to contribute to the exploration of far-off worlds.

Europa, Europa

Ever since Voyager 1 swung by Jupiter in 1979, planetary scientists have been tantalized by the theory that one of the gas giant´s moons, Europa, has liquid water and, perhaps, life. Although Europa is frigid 260 degrees.

![Homebuilt telescopes [foreground] atop Mauna Kea](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/3Y5JXT6QZK3M37INMRKLUVPJ4E.jpg?quality=85&w=485)