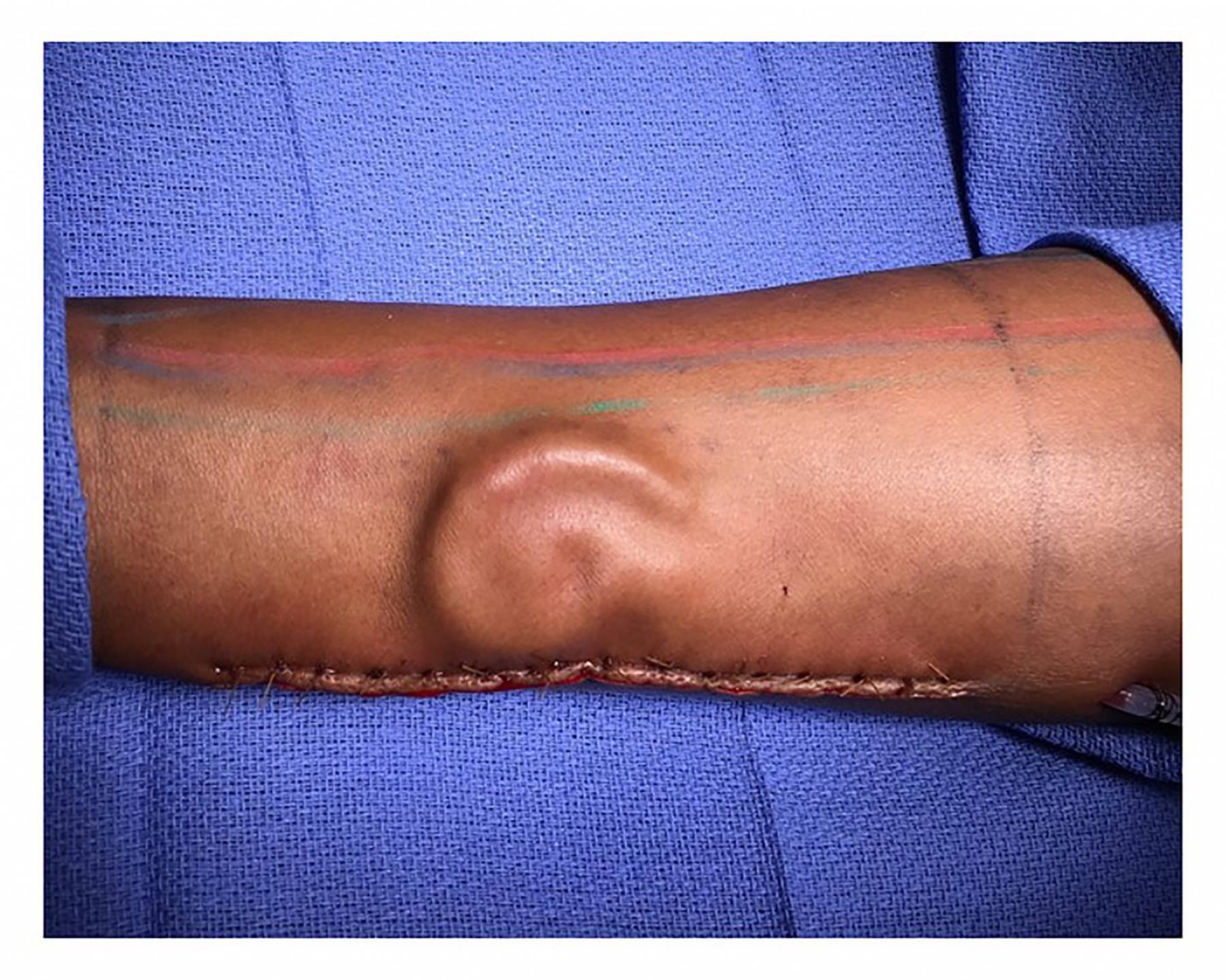

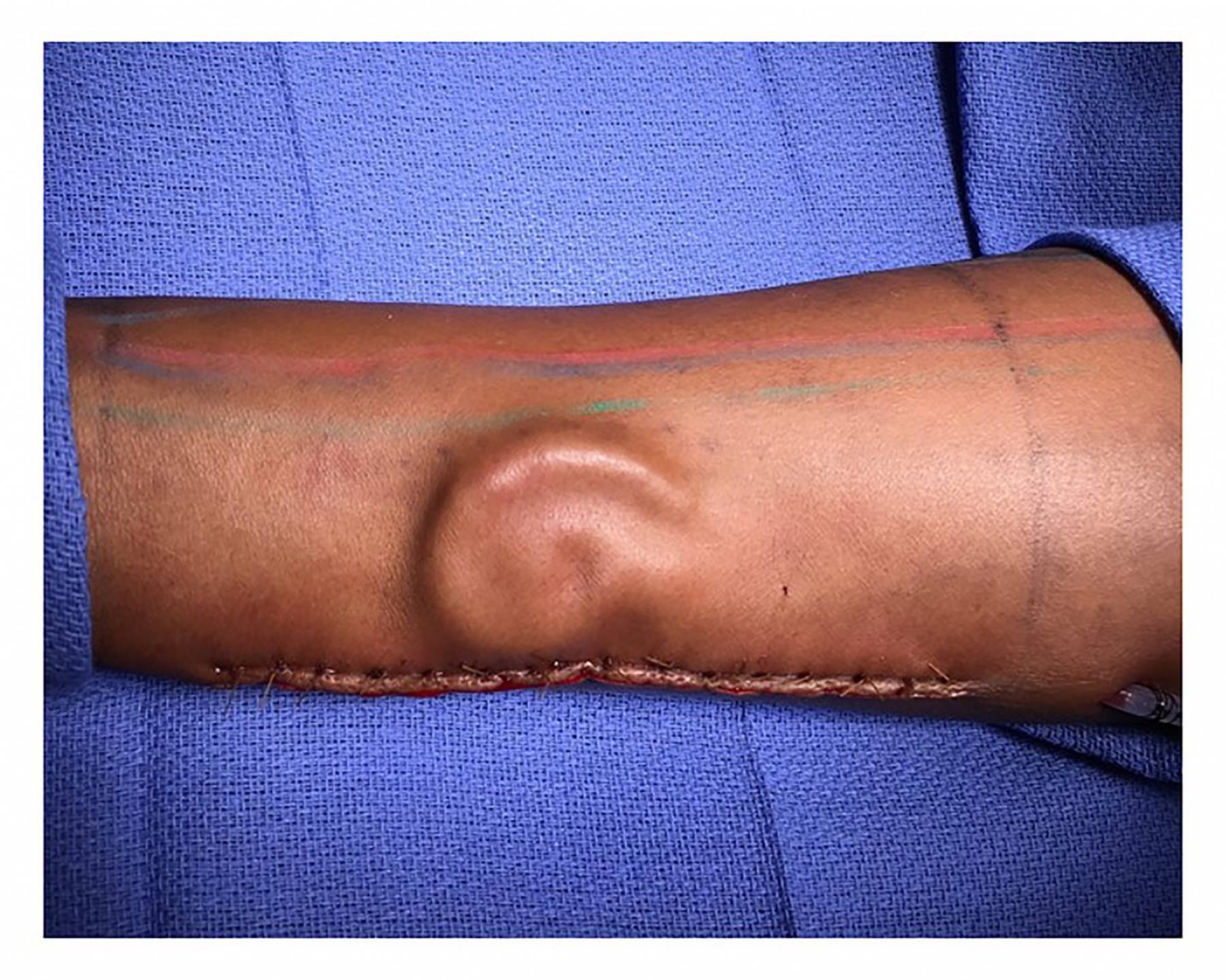

Army private Shamika Burrage was lucky to survive a motor vehicle accident two years ago in Texas, but she lost her entire left ear in the process. Now a new, unorthodox procedure has given her a path to recovery. Plastic surgeons with the U.S. Army successfully pulled off a new kind of total ear reconstruction and transplant, in which they built a new ear from harvested rib cage cartilage, then placed it under the skin of Burrage’s right forearm. They allowed it to grow there for a few months, until it was finally ready for placement on her head.

“The whole goal is that by the time she’s done with all this, it looks good, it’s sensate, and in five years if somebody doesn’t know her they won’t notice,” Lt. Col. Owen Johnson III, the chief of plastic and reconstructive surgery at William Beaumont Army Medical, where the procedure was held, said in a statement. “As a young active-duty Soldier, they deserve the best reconstruction they can get.”

The uncanny quality of this procedure is only matched by its incredible complexity. This is the first time the Army has pulled off this form of total ear reconstruction, but the technique was actually pioneered earlier this decade by Dr. Patrick Byrne, the director of the Division of Facial Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. Byrne trained Johnson himself.

The first part of the procedure involves crafting a new ear out of cartilage, which isn’t anything new. Since the 1920s, in fact, surgeons have used rib cartilage graft as a way to treat microtia, a congenital deformity where the outer ear fails to fully develop. But new surgical tools and procedures have vastly improved the process over time.

“You harvest the rib cartilage, you bury it under the skin behind the ear, let it take, then you elevate the ear in stages and gradually get it covered completely in new skin,” says Dr. Lawrence Lustig, the chair of otolaryngology at Columbia University Medical Center.

The other component to the new reconstruction procedure, and where it really separates itself from previous work, is through what’s called microvascular free tissue transfer, which became popular in the late ’90s. When tissue from one body part is crafted as a replacement for another part, it needs to undergo neovascularization, or the formation of new blood tissues. So doctors will stitch the new tissue to blood vessels in order establish proper circulation. “It’s like a transplant on one’s self,” says Byrne. “99 percent of the time you get a healthy, functioning tissue in a new area.”

In this case, neovascularization is produced by the forearm. “It expands those patients in which you can do a regular reconstruction on,” says Lustig, where a surgeon can’t necessarily go straight to the original location to rebuild the new ear.

Why the forearm? Neovascularization isn’t easy to induce — you’ll want an artery and vein that can nourish the new ear and help it grow. You’ll also want to place the new ear somewhere it’s protected. So the forearm makes the most sense.

It’s important to remember that ear reconstruction can be divided into two different purposes: restoration of cosmetic appearance of the ear, and restoration of functional hearing. These don’t have to be mutually exclusive, but restoring function isn’t always possible if the injuries to the patient are too severe.

Burrage was able to recovery her hearing. If the ear canal is open and the eardrum is undamaged, says Lustig, you simply need to reposition the new ear properly. “But in instances of a very traumatic injury, it’s possible the ear canal is scarred shut. Then you would need to go back and recreate a new ear canal,” or use something like a bone-anchor hearing aid that attaches an implant to the skull and uses the bone itself to transduce sound.

The procedure pioneered by Byrne is still extremely uncommon, mainly because the types of injuries that devastate the ear structure and surrounding soft tissue are themselves pretty rare. And doctors are still working on trying to make sure the resulting ears are durable and resistant to tissue warping, shrinking, and absorption. But Byrne does estimate there are probably a few thousand patients who could benefit from such a procedure.

“I love that this is getting attention,” he says. “I really do think it’s feasible for this to be offered much more,” thanks to advances in tissue engineering that make it easier to artfully craft an ear. “Once that barrier is lowered, I think this becomes a lot simpler. I think it really could be expanded.”

The underlying concepts behind this type of reconstruction—rebuilding the 3D layers of tissue piece by piece, (like bone, skin, mucosa, etc) to create a physiological architecture—are already being explored in other capacities, like in nasal reconstruction. ”We start incrementally creating layers of tissue in the forehead,” says Byrne. “We’ll lift skin off the forehead, we’ll place a skin graft underneath the muscle of the forehead right down to the bone, and lay it back down and let it sit there for several weeks. Then we come back and transfer it and leave it on the face without structure for several weeks; then we split it and lay down cartilage and leave for several weeks.” In the end, the patient has a 3D structure that replicates the nose incredibly well.

Lustig offers a more tempered evaluation of the procedures. “It’s a nice advance and I really like what they’ve done, but it’s not transformative in how we think about reconstruction.”

Can we use this approach to reconstruct more complex tissues and organs? Byrne isn’t sure, but he does think “we may have only scratched the surface of what might be possible.” Incubating components of a structure within soft tissues in the body still sounds like science fiction, but simpler versions of this have been used before, such as planting skull bone into the abdomen to keep it safe before eventual implantation in skull reconstruction. “I think we might be able to come up with additional creative solutions” for applying this technique to complex body parts.

Burrage has two more surgeries to go through before the entire process is complete, but she’s extremely optimistic so far. “It’s been a long process for everything, but I’m back,” she said.