People with chronic conditions, like asthma or heart disease, often need to take medications on a daily basis. But that simple act of remembering each day is a huge problem for many. In fact, for certain conditions, less than 50 percent of people take their medications on time. But researchers at MIT and Brigham and Women’s hospital in Boston have come up with a solution: A single pill that sits inside the stomach and delivers medication over an extended period of time.

The new device, which has been tested in pigs, could be a potential solution not only for patients with chronic diseases, but also as a way to treat conditions in third world countries that require long-term therapies, such as malaria. The researchers published the results of their proof-of-concept study in the journal Science Translational Medicine on Wednesday.

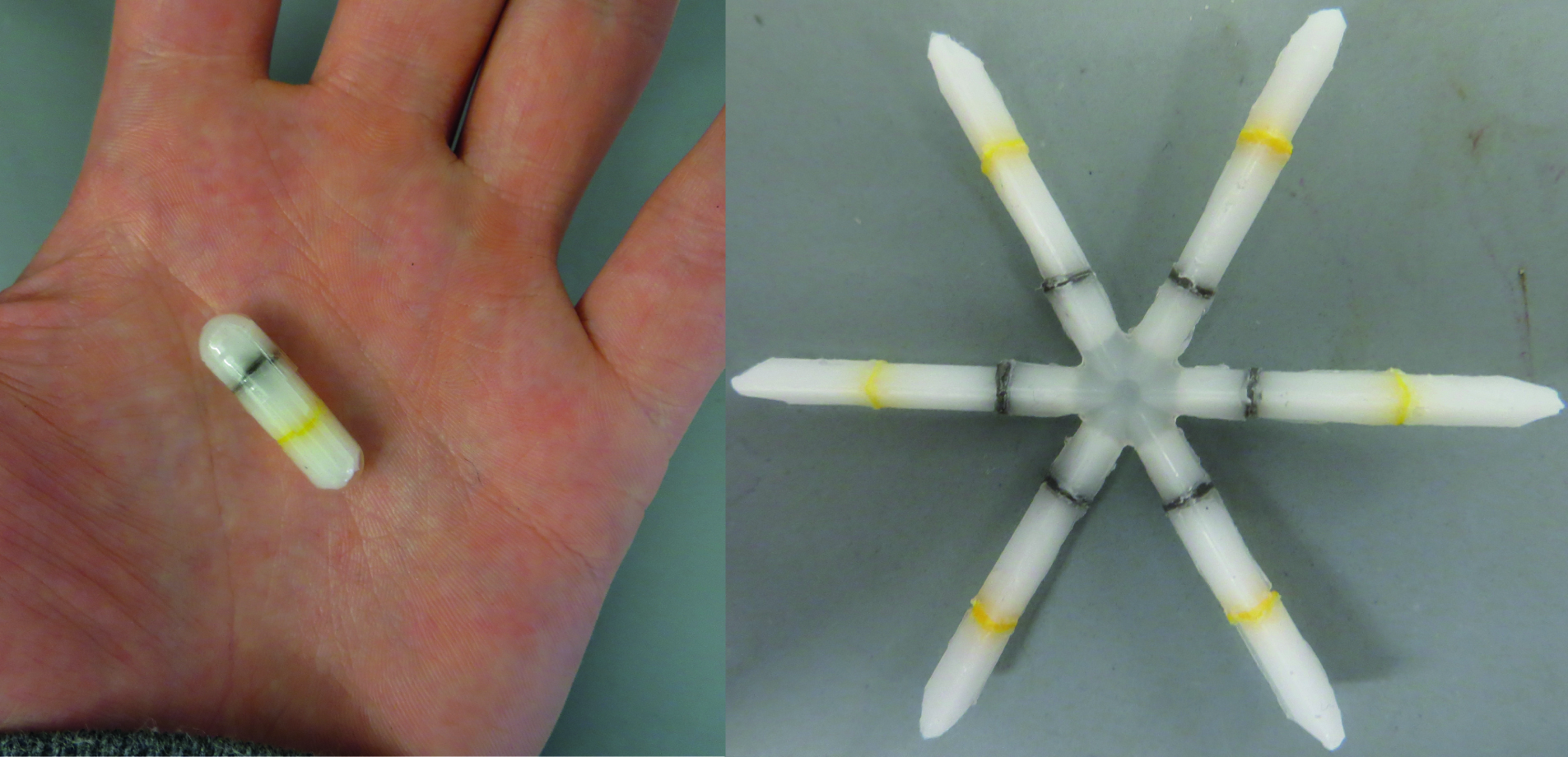

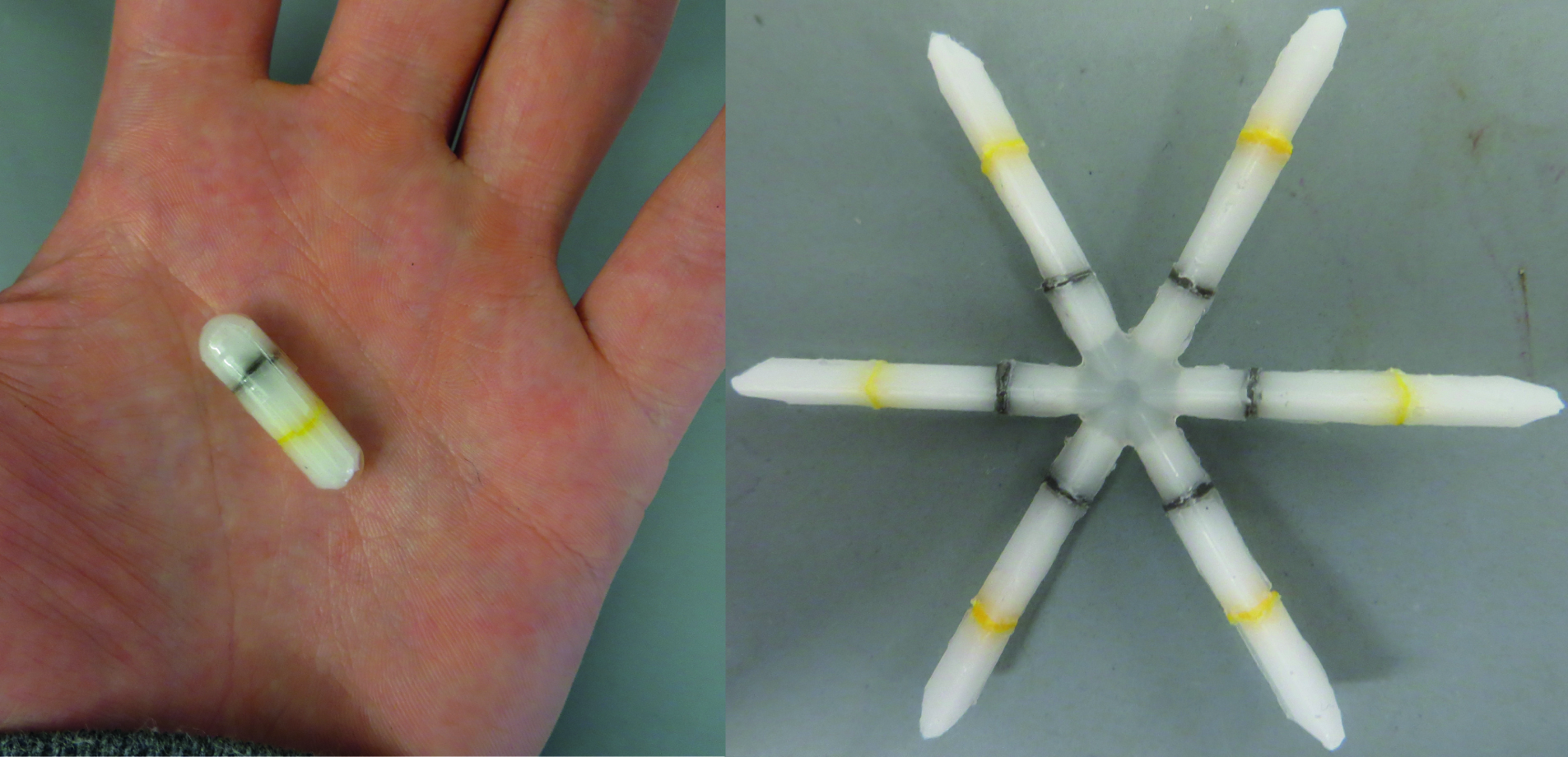

The pill had to overcome some major hurdles. The stomach contains extremely strong muscles that ensure every last drop of food makes its way out into the small intestine, so it’s hard for pills to have staying power. To combat this, the researchers designed the drug so that when swallowed, the capsule opens up into a sort of star. This shape prevents the pill from leaving the stomach and entering the small intestine.

While the pill’s unique shape keeps it stuck in the stomach at day’s end, a special polymer coating ensures that pre-determined doses are released into the body one by one. Once the pill releases the last dose, it breaks apart and can finally pass out of the stomach and into the small intestine.

The researchers note that this type of therapy could be useful in treatments for conditions like high blood pressure or diabetes, which don’t cause distress to patients every day and can therefore often go unnoticed.

“Some of these diseases do not have symptoms that are perceived daily and in fact are silent to some degree,” says Giovanni Traverso, lead author of the study and a gastroenterologist and biomedical engineer at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

There are extended-release and even delayed-release tablets on the market today, but even those are forced out of the stomach by day’s end. For truly extended release, physicians and patients must currently turn to patches, implants, and intravenous drug delivery.

Aside from daily drug delivery in first world countries, the researchers note that the technology could have a major impact on treating diseases that plague the third world. The project was partially funded by the Gates Foundation in an effort to find better methods to combat malaria. The researchers focused their initial studies on using an anti-parasitic drug called ivermectin, which significantly reduces a person’s chances of getting malaria when taken over extended periods of time. When tested in pigs, the device releases ivermectin in small, sustained doses for up to 10 days.

The technology is far from ready to hit the markets, though. The researchers plan to test the device more in pigs, with different medications and different doses, before they move on to humans.