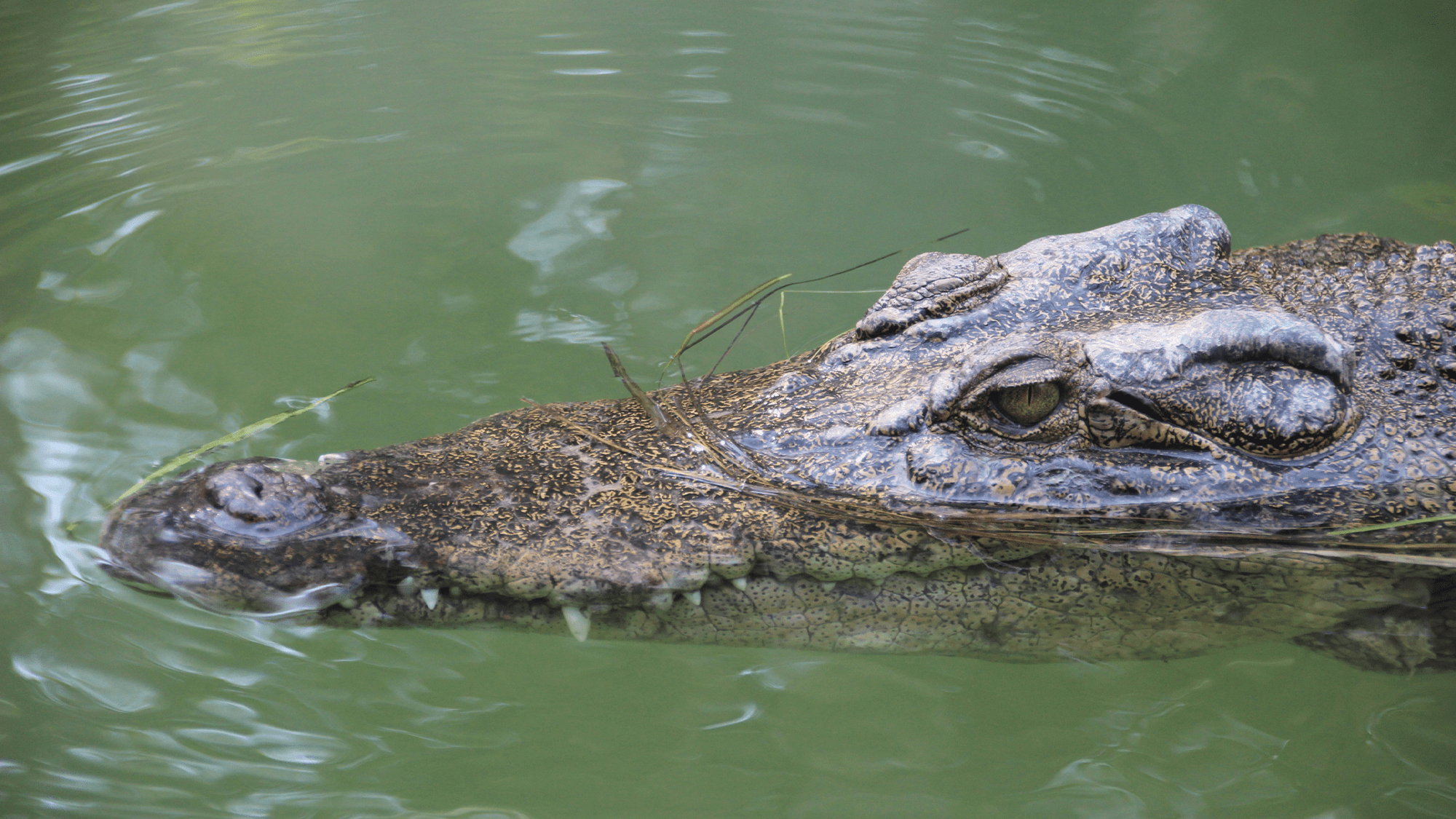

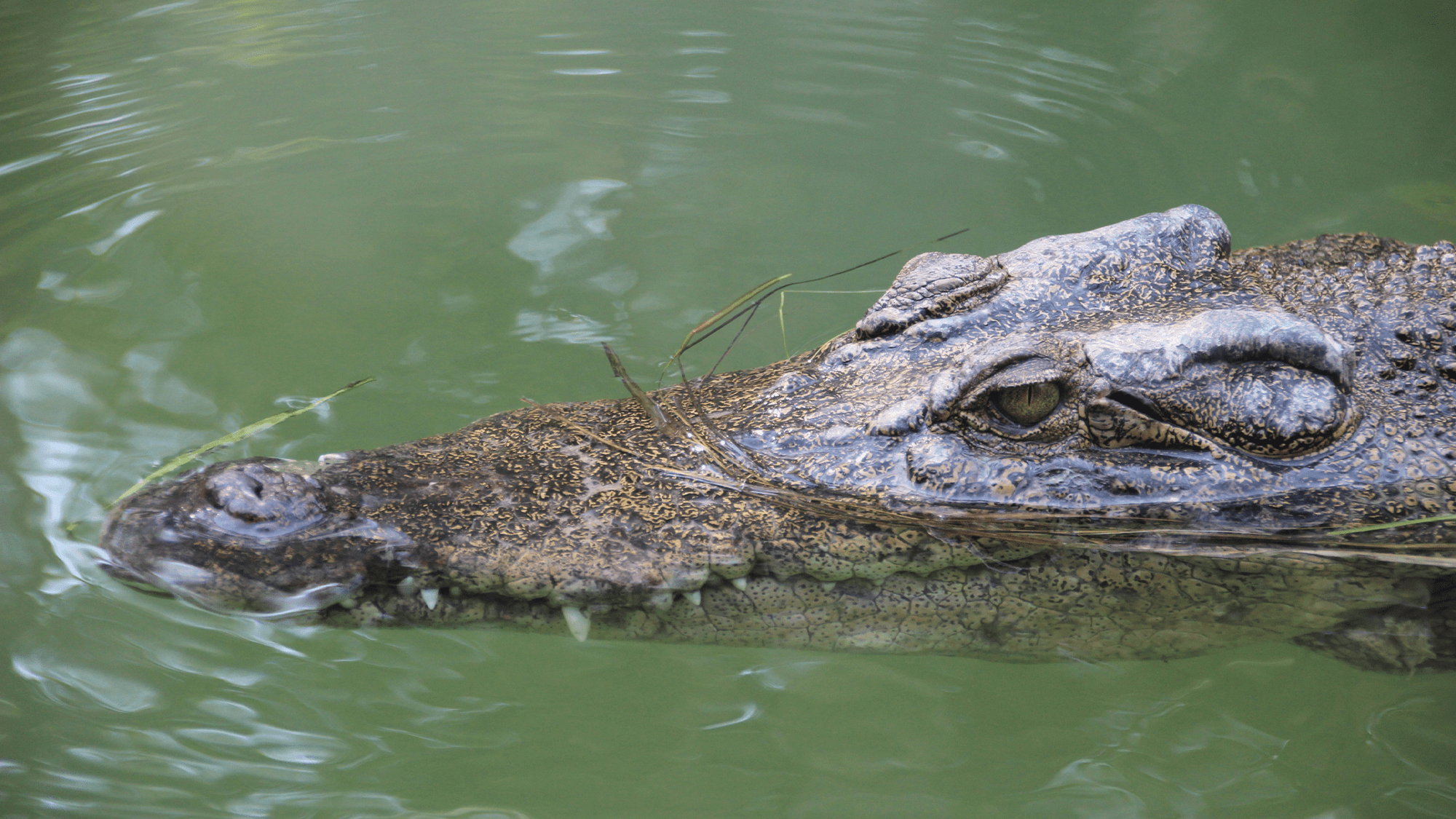

Even Australia’s most fearsome predators aren’t all safe from the stinging bites of mosquitoes—and the threat of West Nile virus (WNV) that comes with it. Saltwater crocodiles (or salties) can develop skin lesions called pix as a result of a pesky mosquito bite, and further transmit the virus.

[Related: Snorkeler pries crocodile’s jaws off his head to survive attack.]

Scientists are a bit unsure how a mosquito can bite the tough hide of a saltwater crocodile. Some experts believe that it could be that the thinner membranes around the crocodile’s eyes and inside the mouth are easier for mosquitoes to penetrate and then release the virus.

Nevertheless, some help could be on the horizon in the form of a croc vaccine.

The results of a trial for a vaccine candidate that can protect salties from WNV were published June 27 in the journal npj Vaccines. University of Queensland virology professor Roy Hall and his team investigated two vaccine candidates in saltwater crocodile hatchlings.

Both of the vaccines were made of genes from a virus specific to insects called Binjari virus and structural proteins of WNV. Groups of 70 crocodile hatchlings were immunized through the muscle or in the fatty layers of the skin with two doses of either the Binjari virus or WNV vaccine at four week intervals.

“We were very pleasantly surprised that our vaccine produced such a robust protective immunity in crocodiles,” Hall tells PopSci. “All our previous studies with this type of vaccine had been in mammals and we were not sure what the response would be like in a cold-blooded reptile.”

One reason that scientists are so concerned about the skin lesions on crocodiles is that in Australia, crocodile farming is still allowed. “Crocodiles contract the infection from mosquitoes in both farmed and wild environments,” Hall says. “However, there is good evidence that in some cases, infection can also pass directly from crocodile to crocodile in a farm situation – this is less likely to occur in the wild where the density of animals is much lower and direct contact less frequent.”

According to the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in Australia, crocodiles have been farmed to produce luxury goods like handbags and belts, as well as for their meat in Australia’s Northern Territory since the late 1970s, partially as a response to decades of overhunting. Government approval is given to businesses to harvest up to 100,000 eggs total from the wild annually in the country’s Northern Territory.

While croc farming is not officially banned, it does come with ethical concerns. Confinement and crowded conditions from breeding can lead to stress in the animals due to lack of space to move, eat, and interact with other animals. The Australian Government has issued a Code of Practice for the humane treatment of the crocodiles and it is illegal to capture or farm wild crocodiles in the state of Queensland. People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) Australia still continues to stand against crocodile farming, with Australian supermodel Robyn Lawley speaking out on PETA’s behalf against the use of crocodile farms in the luxury fashion industry.

[Related: These mosquito-borne viruses have a bizarre way of making you smell sweeter to their minions.]

Saltwater crocodiles were on the brink of extinction in the early 1970s due to hunting. Salties are now a protected but vulnerable species with roughly 20,000 to 30,000 in Queensland. In the Northern Territory, they are no longer considered a conservation concern.

Some conservationists, including crocodile expert Grahame Webb, attribute placing economic value on crocodiles as part of the solution to bringing sustainable benefits to the Northern Territory and conserving crocs.

“Croc farming promotes sustainable practices and has played a pivotal role in returning saltwater crocs from the brink of extinction in recent times. By placing an economic value on crocodiles, communities living with or near crocs are more tolerant of their presence and are encouraged to protect their habitats,” says Hall. “Protecting the viability of this industry also benefits other species that co-inhabit with crocs eg. brolga, jabiru and long-necked turtle.”

The results of this vaccine trial suggest that the vaccine candidate is safe and effective for preventing the skin lesions in farmed crocodiles. The team recently received funding from the Australian Research Council to work with the Centre for Crocodile Research to better assess the vaccine’s performance in the long term and in a larger trial with the hope of mass producing it for more immunization.

“[This study] demonstrates how research on understanding the basic biology and biodiversity of obscure microorganisms can lead to very important biotechnological advances to solve major problems for industry and veterinary and human health,” says Hall.