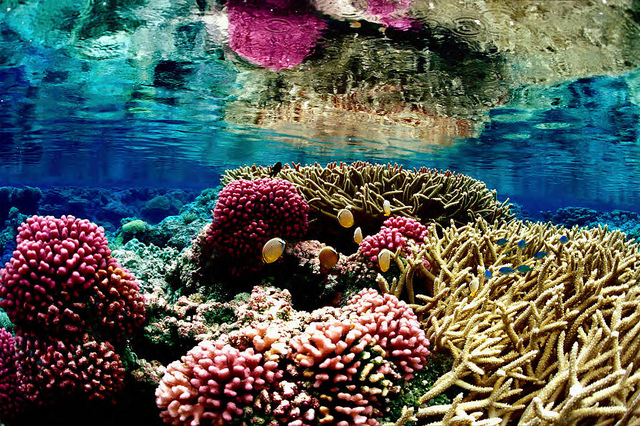

As ocean temperatures continue to soar, the world’s coral reefs all over the world are in danger from climate change, disease, and destructive human activities. In response, scientists are testing various ways to help, from intentionally bleaching them to preserve fragments to coloring their larvae to study reproduction, and transplanting coral fragments to regrow damaged reefs.

According to a study published March 8 in the journal Current Biology, planting new coral in some degraded reefs can help it grow just as quickly as healthy reefs after only four years. The study was conducted at the Mars Coral Reef Restoration Programme in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, one of the biggest reef restoration projects in the world.

[Related: World’s largest known deep-sea coral reef is bigger than Vermont.]

“Large areas of reefs in South Sulawesi have been destroyed by destructive dynamite fishing 30 to 40 years ago,” Ines D. Lange, a study co-author and marine biologist at the University of Exeter, tells PopSci. “The degraded areas have not recovered since, as loose coral fragments rolling around on the ground crush any new coral larvae that try to settle.”

Dynamite or blast fishing is an illegal practice where explosives are thrown into the water to stun or kill fish. Coral reef species can pay a hefty price, as the blasts can loosen coral fragments and the indiscriminate killing of anything nearby disrupts the food web.

The Mars program is working to restore degraded reefs by transplanting these coral fragments onto a network of interconnected structures called Reef Stars. These sand-coated steel frames that help keep them in place.

A team from the University of Exeter collaborated with the Research Center for Oceanography, National Research and Innovation Agency in Indonesia, Mars Sustainable Solutions, and Lancaster University to monitor reef carbonate budgets as the Reef Stars were planted. A reef carbonate budget is the net production or erosion of reef framework over time. They’re a key predictor of a reef’s ability to grow, keep up with rising sea levels, protect the coast from storms, and provide a key habitat for reef animals.

After planting the Reef Stars, the team measured the carbonate budgets on the restored reef sites after a few months, one year, two years, and four years. These measurements gave them a sense of the rate that the reef’s functions were returning to normal. To compare, they also measured the carbonate budgets of degraded reefs and healthy control sites.

[Related: Some Pacific coral reefs can keep pace with a warming ocean.]

In the years after coral transplantation, coral cover, colony size, and carbonate production tripled, according to the study. After four years, the restored sites were nearly indistinguishable from nearby healthy reefs. They were growing at the same speed as healthy reefs, while providing a similar habitat for marine life and protecting adjacent islands from coastal erosion and storm waves.

“We did not expect to see a full recovery of overall reef growth in such a short time, which was a very positive surprise,” says Lange.

However, the composition of the reef community on the restoration site in this study was different from what usually makes up a healthy coral community. This is because the transplanted coral fragments were a mix of different branching coral types. The community composition may affect how well the reef’s structure holds up for some larger marine species and the resilience to future heat waves, since branching corals are more sensitive to bleaching.

Longer-term study is necessary to see what happens to the restored reefs over time, but Lange says that this work is an example of how active management can help boost the reef’s resilience. The team is hopeful that the restored reefs will naturally recruit a more diverse mix of coral species over time.

“We are currently investigating other ecosystem functions on the same restored reefs to get a bigger picture of the ability of reef restoration to bring back fully functioning reef ecosystems,” Lange says. “It would also be interesting to use the same methods as in this study on other reef restoration projects worldwide to assess the recovery in different environmental settings or across different restoration methods.”