This article was originally featured on Hakai Magazine, an online publication about science and society in coastal ecosystems. Read more stories like this at hakaimagazine.com.

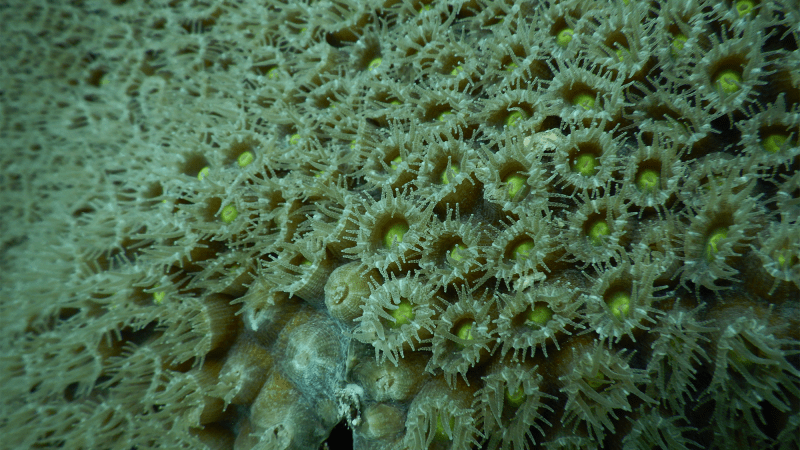

Vetea Liao was late. Two or three times a week, the Tahitian-born marine scientist heads out for an early-morning dive. He likes to start just as the first rays of light break the horizon. But that morning, in November 2014, the sun was already warming the lagoon off Moorea, Tahiti’s sister island in French Polynesia, when Liao hit the water. Peering down, Liao spotted the familiar branches of Porites rus, a common coral around the archipelago’s western islands that looks a little like ginger root studded with strawberry seeds. He also saw something else: something he’d never seen before. A delicate fog was rising up from the reef. It looked like the coral was smoking.

Liao sought out his colleagues at Moorea’s French Centre for Island Research and Environmental Observatory (CRIOBE). No one had ever seen anything like it. But one offered a lead: maybe the coral was having sex? It was a bold hypothesis.

Coral reproduction is thought to be largely a nighttime activity. In response to environmental cues—the full moon, temperature fluctuations, even the duration of darkness—corals simultaneously release clouds of tiny eggs and sperm into the water, which are fertilized and then float with the current and eventually settle on a new patch of reef. Scientists had witnessed corals spawning in daylight just a handful of times before 2014, but never in French Polynesia. Could the P. rus Liao had seen really be doing it, too?

For years, though he returned to the lagoon many times, Liao didn’t see the coral haze again. Then, in 2018, a friend spotted misty waters from her deck, which overlooks a different lagoon in Tahiti. As with Liao’s initial sighting, it was just a few hours after dawn. With confirmation of when to search, Liao soon got proof that the haze was what his colleague had suspected: the sure sign of coral spawning in daylight. Within the next two years, he and a dozen others recorded daytime spawning events across Tahiti, Moorea, and four other islands in the archipelago. P. rus sex, he eventually found, occurs like clockwork: five days after the full moon, from October to April, about two hours after daybreak—roughly 7:00 a.m. in French Polynesia. On deeper reefs, P. rus does the deed later, around 10:00 a.m.

Liao now has a team of more than 100 locals—families, schoolkids, fishers, and volunteer divers—who have reported 226 daytime spawning events by P. rus, surveying more than 100 reefs on 14 islands, including several remote atolls. “Without citizens, it would have taken ages to know all this,” Liao says.

In 2020, marine biologist Camille Leonard witnessed the precision of daytime spawning at CRIOBE, where she was monitoring P. rus coral growing in tanks at the same time that divers were surveying a nearby reef. “The Porites spawned at the exact same minute [in the two places],” Leonard says. Liao’s timing was spot on. “I thought, Okay, he knows what he’s doing,” says Leonard.

That remarkable synchrony extends far beyond Polynesia. In December 2022, after reading about Liao’s work on Facebook, coral scientist Victor Bonito with Reef Explorer Fiji P. rus recorded coral spawning two hours after sunrise in Fiji, more than 3,000 kilometers away. The same is true near the island of Réunion, 15,000 kilometers away in the Indian Ocean. In general, though, observations of daytime spawning remain staggeringly rare. Liao hasn’t yet published his research, which he conducts through the nonprofit Tama No Te Tairoto (Children of the Lagoon in Tahitian) outside his full-time job developing sustainable pearl farming for French Polynesia’s Department of Marine Resources. Publishing is secondary, he says, to sharing knowledge with the locals who have helped survey the reefs.

The team’s work is impressive. “I have not heard of such an extensive citizen science project for coral spawning before,” says James Guest, a coral researcher at Newcastle University in England who launched the Coral Spawning Database. Liao’s contributions to the database, which gathers and shares data on coral spawning times in the Indo-Pacific, filled scientific gaps about Porites corals. “In the Indo-Pacific particularly,” Guest says, “there’s so much focus on Acropora [corals].”

Equally impressive is that this new discovery is already being put to work for the coral’s benefit. Thanks to Liao’s research, two of the biggest environmental consulting companies in French Polynesia now recommend that developers stop all work in nearby coastal areas during the P. rus spawning period to avoid disturbing reproduction.

As the climate continues to change, says Guest, it’s possible that corals in the Porites genus will begin to dominate reefs in the Indo-Pacific. Porites corals are tough, he says. They can handle conditions that challenge other corals, including heat, ocean acidification, and murky water. They also spawn more frequently. “It’s fair to say they are a bit more resistant,” Guest says. But “if [their reproduction] is disrupted, reef recovery could be slower or nonexistent,” he adds.

What actually triggers the special spawn timing of P. rus, though, is still unknown. It could be a certain amount of solar radiation, a precise rise in temperature, both, or something else. But Liao isn’t done investigating. Using some of Tama No Te Tairoto’s limited funds, he recently installed light meters on reefs to investigate if spawning is related to a specific wavelength of light. “Maybe it will remain a mystery,” he says. Whether or not Liao can pinpoint the triggers, corals around the world continue to do it, right on cue, in the light of day.

This article first appeared in Hakai Magazine and is republished here with permission.