In 1847, German biologist Carl Bergmann posited that cold climates give rise to bigger bodies, and that animals who live in warm places typically are smaller. It made sense, since bigger bodies preserve heat more efficiently than smaller ones.

One question remained unanswered. What about birds who endure both hot and cold? As it turns out, it’s all about the heat, a fact made clear by climate change.

Birds are shrinking, and the culprit appears to be rising temperatures, according to new research in the journal The Auk: Ornithological Advances. Nestlings that mature during hot summers grow into smaller adults, and they stay that way — even if the birds also live through cold winters. Scientists now suspect that exposure to excessive heat is a stronger influence on body size than bitter cold, a finding that raises worrisome implications about the health of birds on a warming planet.

Scientists studied house sparrows, but “many species might get smaller,” said Simon Griffith, a researcher at Macquarie University in Sydney, and a senior author of the study. But he cautioned that it’s still not clear what this means. “This might be an adaptive response, and may make animals better able to cope with changing conditions,” he said. “The key thing is to understand why it is happening and what the fitness consequences are likely to be for animals — that is, are they better off or worse off in a warming world?”

Doctoral candidate Samuel Andrew, the study’s lead author, agreed, adding, “If these changes in size are an important part of adapting to warmer climates, then birds that don’t change their size in response to temperature change could be the species that are more vulnerable.”

The latest study adds to a growing body of research showing that animals are undergoing changes in response to increasing temperatures. Last summer, Canadian researchers reported that many species of fish were shrinking in response to climate change — some by as much as 30 percent — because warming ocean waters make it difficult for them to absorb the oxygen they need.

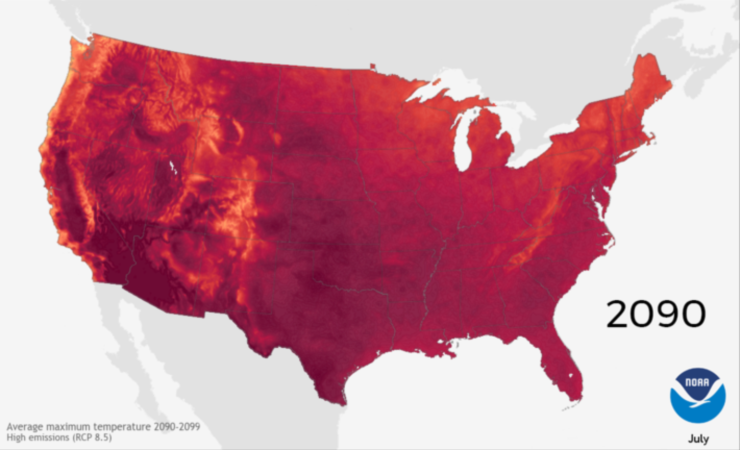

“The overall pattern between temperature and body size has been seen in lots of organisms,” Griffith said. “What we are suggesting is that more people need to consider that it may be driven by problems caused by developing in very hot weather. We know that heat waves are increasing in severity and intensity, and therefore this could be driving the shrinking of animals.”

For the study, Andrew and his team captured and measured about 40 adult house sparrows at each of 30 locations across Australia and New Zealand. They found that maximum temperatures during the summer, when the birds breed, were a better predictor of adult body size at each location than winter minimum temperatures.

Because house sparrows are sedentary birds that live among humans, “this means you can compare the size of birds from different locations across a large distribution,” said Andrew, the study’s lead author. “The interesting thing about the Australian [sparrow] populations is that some of them live in the arid center of Australia, where it gets very hot during the summer, but also cold during the winter. This is in contrast to more mild changes between the seasons for populations closer to the coast, or in the tropics. We expected that the hottest temperatures during the summer, or the coldest temperatures during the winter, would be most relevant to the survival of the birds.”

But that’s not what they discovered. “We found that house sparrows are more likely to be smaller in locations with hot summers, and that there was no significant relationship between winter temperatures and size,” Andrew said. Scientists believe birds are regulating their development in response to the heat, conserving resources that would otherwise be used to grow larger.

Researchers chose to study house sparrows because the species exists across a wide swath of climates, from the Arctic Circle in Norway to the middle of Australia, Andrew said. “If we can understand the key traits that allow this species to be successful in such a range of climates, then we can do a better job of evaluating which species need the most help when it comes to climate change,” he said. “We just don’t know yet.”

Griffith agreed. “One of the big challenges for biodiversity generally is that the speed with which the climate is changing is faster than ever before,” he said. “That means that the capacity of different species to respond is going to be key to determining the extent to which they can cope.”

Marlene Cimons writes for Nexus Media, a syndicated newswire covering climate, energy, policy, art and culture.