Think of it as a study of the natural behaviors of the troll. A team of information science researchers recently analyzed the comments people make on recorded TED talks. Actually, the researchers found that the majority of comments related to the content of the talks (progress!). But they also found that about six percent of YouTube comments on TED talks are insults and that female TED presenters are more likely to have commenters assess their appearance and style than male presenters (not progress).

TED is a nonprofit dedicated to putting on conferences with short lectures. It also posts its lectures online. This analysis of TED comments comes at a time when news and science media are still trying to figure out what to do about commenters. This weekend, the Chicago Sun-Times announced it’s temporarily shutting off comments while it puts in a new system designed to “encourage increased quality of the commentary.” Here at Popular Science, where we have a small staff for the website, we decided to remove comments from our homepage about seven months ago. You can still reach us via email, Facebook, Twitter , Tumblr, Instagram and snail mail.

TED talks are supposed to be fun and good for you, kind of like chocolate-chip granola bars.

In a paper they published in the journal PLOS ONE, the TED-analyzing researchers said they were hoping to gather some insight for science communicators. TED talks are 18-minute lectures about intellectual ideas, aimed at non-experts. They’re supposed to be fun and good for you. Kind of like chocolate-chip granola bars? Anyway, the largest portion of the talks are about science and technology. As of November 2013, the researchers counted 917 science and technology TED talks, compared to 313 talks about design and 265 talks about entertainment. So the researchers, a team from the U.S., the U.K. and Canada, looked at TED talks as a proxy for, How do people respond to popular science media? They restricted their analysis to comments on science and technology talks only.

One of their big findings was that the website people use matters. TED talks are posted both on ted.com and YouTube, but comment trends differed a bit on the two platforms. After analyzing comments for the same set of 595 talks, the research team found that people were more likely to talk about the content of the video—rather than, say, about the speaker’s looks or themselves—on the TED website than on YouTube. That said, the ted.com comments weren’t always that deep. Many comments just reiterated points from the talk, the researchers noted. And the majority of YouTube comments, 57 percent, still referred to the content of the TED talk. It’s just that an even larger portion of ted.com comments were on topic, 72 percent.

People were more likely to throw around personal insults on YouTube (5.7 percent of comments) than on ted.com (less than one percent of comments). YouTube did have one advantage. YouTubers were more likely to engage with one another than ted.com commenters. But if they’re just insulting each other, maybe that’s not so helpful.

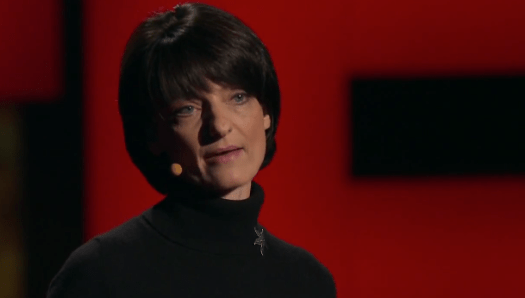

Commenters were more likely to discuss female presenters’ looks than male presenters’ looks.

Another major finding was that commenters react differently to male and female TED presenters. Commenters were more likely to discuss female presenters’ looks (15 percent of comments) than male presenters’ looks (10 percent of comments). Female presenters were also more likely to elicit both positive and negative comments about themselves than male presenters. People react really emotionally to lady TED talkers, I guess. Male and female TED presenters didn’t have any statistically significant differences in the positive and negative comments they received about the content of their talks.

So it sounds like TED-talk comments aren’t necessarily super intellectual, but they aren’t a cesspool, either. Yay? In addition, perhaps TED should keep a sharper eye out for off-topic or hateful comments about its female speakers. It might help if the organization had more talks led by women in general. Another analysis, published about a year ago, found that women give less than a quarter of TED talks.