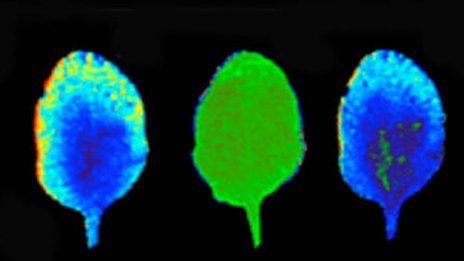

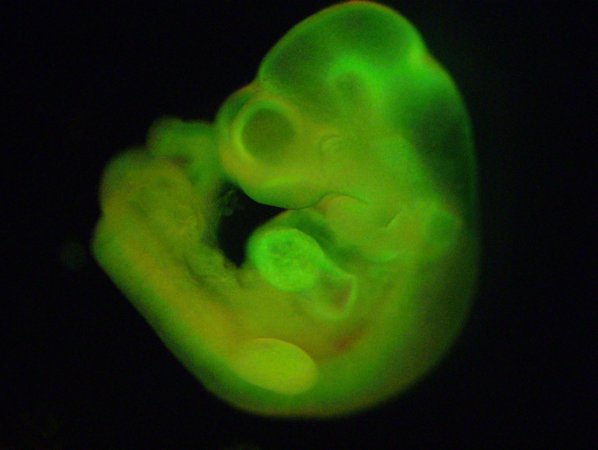

In animals, a tumor develops when a cell (or group of cells) loses the built-in controls that regulate its growth, often as a result of mutations. Plants can experience the same phenomenon, along with cancerous masses, but it tends to be brought on via infection. Fungi, bacteria, viruses, and insect infestation have all been tied to plant cancers. Oak trees, for example, often grow tumors that double as homes for larvae.

The good news for plants is that even though they’re susceptible to cancer, they’re less vulnerable to its effects. For one thing, a vegetable tumor won’t metastasize. That’s because plant cells are typically locked in place by a matrix of rigid cell walls, so they can’t migrate. Even when a plant cell begins dividing uncontrollably, the tumor it creates remains stuck in one place usually with minor effects on the plant’s health—like a burl in a redwood tree.

Plants also have the benefit of lacking any vital organs. “It’s bad to get a brain tumor if you’re a human,” says Elliot Meyerowitz, a plant geneticist at the California Institute of Technology. “But there’s nothing that you can name that’s bad to get a tumor in if you’re a plant. Because whatever it is, you can make another.”

Meyerowitz points to another difference between plant and animal oncology with regard to those redwood burls: “Instead of treating plant tumors by surgery and chemotherapy, we make them into cheesy coffee tables.”

This article originally appeared in the February 2014 issue of Popular Science.

![Homebuilt telescopes [foreground] atop Mauna Kea](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/18/3Y5JXT6QZK3M37INMRKLUVPJ4E.jpg?quality=85&w=485)