Shortly after iron swords and spearheads became common, soldiers in sixth-century Greece ran into a problem. Infantrymen carted around breastplates, helmets, bronze-lined wooden shields, and iron-tipped spears—as much as 70 pounds of extra weight. The loads were so intolerable that soldiers routinely abandoned them on the battlefield. The famous Spartan phrase “Come back with your shield or upon it” was not meant to inspire valor. It was a directive to stop troops from ditching essential equipment.

“The ability to move is directly related to the ability to survive.”

Since then, machine guns have replaced heavy javelins, but the weight soldiers carry into war has remained stubbornly consistent: Today, as in Roman times, the average foot soldier lugs about 55 percent of his bodyweight into combat. And though Kevlar is much lighter than bronze, new field tools such as radios, night vision goggles, and all the batteries necessary to power modern war have offset any lightening of loads.

That’s a significant issue. “The ability to move is directly related to the ability to survive,” says Lee Mastroianni, program manager at the Office of Naval Research. During the D-Day invasion of Normandy in World War II, for example, many U.S. Army soldiers drowned while attempting to wade ashore with 90 pounds of gear. Today, musculoskeletal injuries to the knee and back prompt twice as many medical evacuations from Iraq and Afghanistan as combat injuries, and they’re the number one reason for medical discharge from the U.S. military.

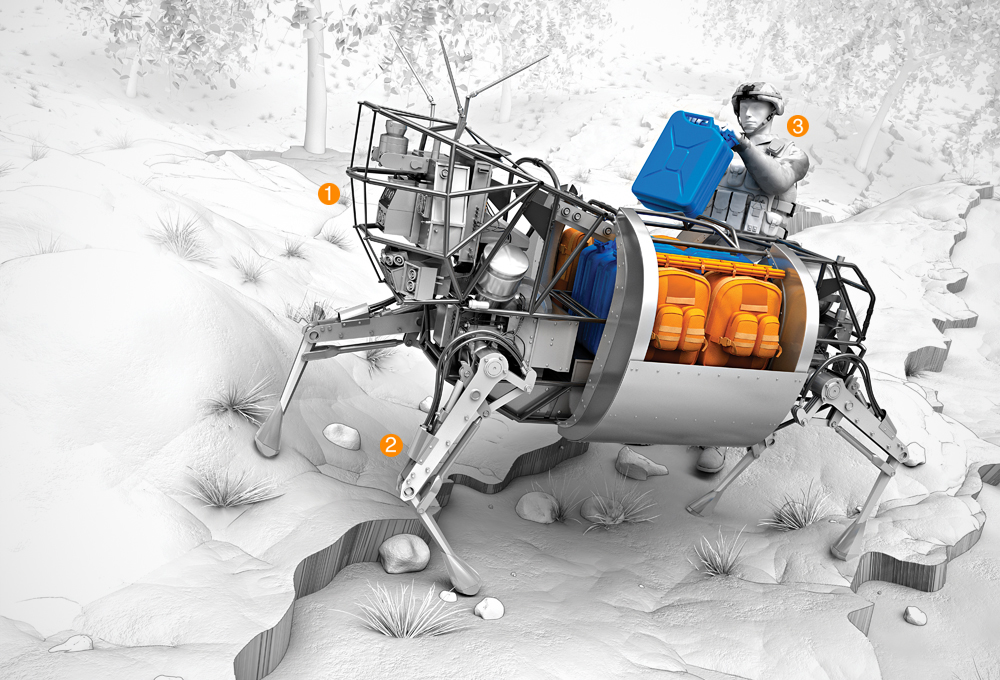

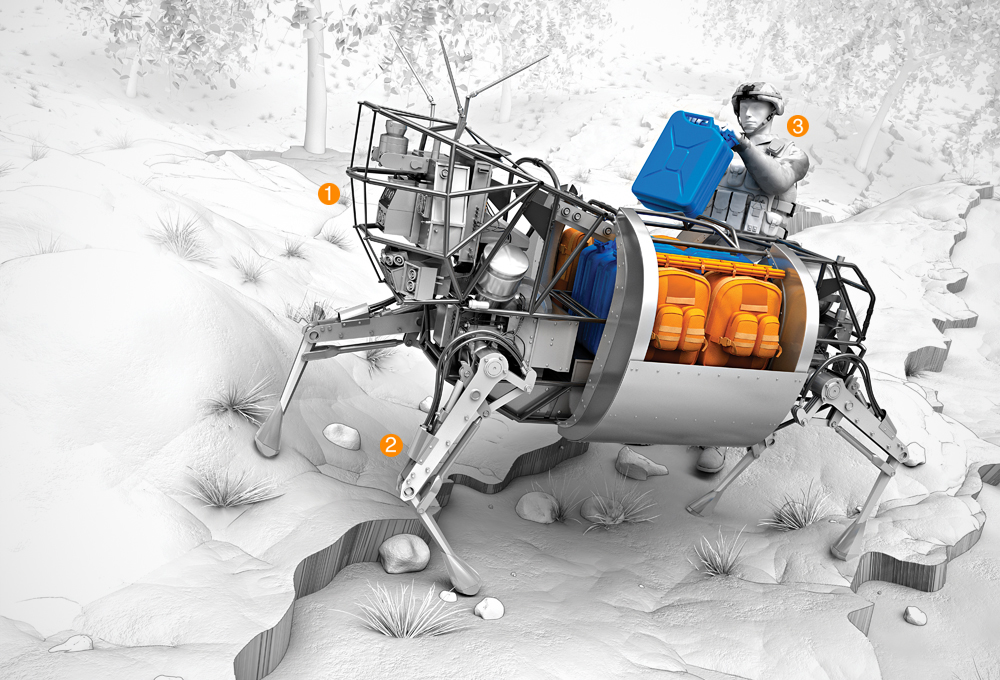

But new technology is now driving in-the-field solutions, helping scientists develop new ways to lighten troops’ burdens. Some shave away existing weight. Others, such as a real-life Iron Man suit or a robot mule, shoulder the load. But all of them will change how soldiers fight, making the terrible business of war just a little more bearable.

Click through the images below to explore emerging technologies that will help carry soldiers’ burdens.

This article orginally appeared in the November 2014 issue of Popular Science under the title, “The Weight Of War.”