This post has been updated.

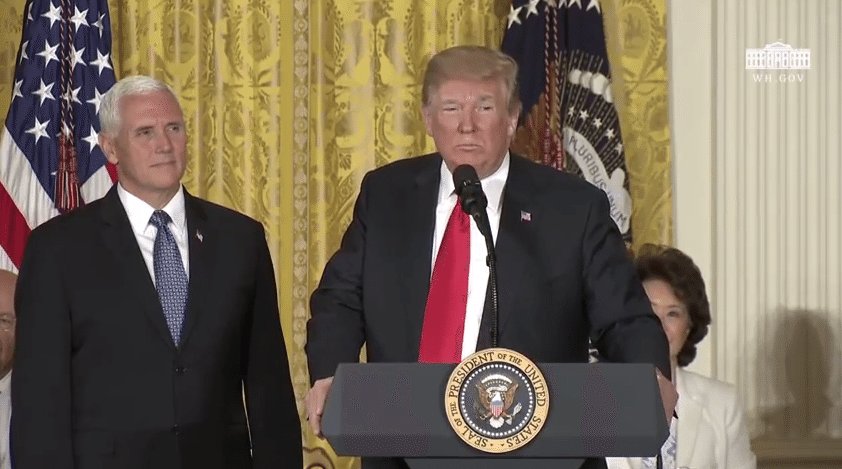

At a meeting of the National Space Council at the White House on Monday, President Trump announced that he was directing the Department of Defense to create a “Space Force” as a sixth branch of the military.

Initially scheduled for 11:30 a.m. EDT, the meeting started 45 minutes late and opened with remarks from President Trump. After first discussing employment numbers, immigration, and other varied topics, Trump announced that he was directing the Pentagon to create a sixth branch of the military, a “Space Force,” and he tasked Gen. Joseph F. Dunford Jr., the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff with carrying out that assignment.

Trump spent just one minute and 43 seconds of his approximately 20 minute address to the Council speaking about the creation of the Space Force. In contrast, he devoted over twice that amount of time—three minutes and forty one seconds—to immigration. The administration is currently facing a public backlash to its immigration policy of separating parents and children at the border. During the remaining hour and a half of the Council’s meeting—which Trump was not present for—the topic of the Space Force did not resurface, leaving many aspects of Trump’s instruction to Dunford a mystery.

Currently, many space launches in the United States are overseen in part by the Air Force Space Command. The military has been involved in American space ventures since the early days of the space race, helping develop many early rockets. The first astronauts were also pulled from military pilots, and many modern members of NASA still get their start as pilots and engineers in the armed forces. Trump spoke earlier this year about the creation of a Space Force, without many details as to what that would look like.

The creation of a military branch dedicated to space is a delicate matter; in 1967, the United States was one of many countries to sign the Outer Space Treaty, intended to prevent conflict in the course of off-world exploration. The language of that treaty prohibits members from stationing nuclear weapons and weapons of mass destruction in space, and from building fortifications on the moon or other celestial bodies. In 2014 the U.S. elected not to sign a separate treaty explicitly prohibiting extraterrestrial weapons.

The announcement comes just as delegates from around the world are convening in Vienna for the 50th anniversary of the United Nations Conference on the Exploration and Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. The annual meeting of the UN Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) is also meeting this week. The Committee is where treaties like the Outer Space treaty were forged back in the 1960s.

One of the people in Vienna for the meeting is Chris Johnson, the Space Law Advisor for Secure World Foundation, a nonprofit dedicated to ensuring the secure, sustainable, and peaceful use of outer space.

“What we were going to be discussing at COPUOS were guidelines for long term space sustainability and how not to cause more space debris, how to be transparent in your actions in outer space,” Johnson said. “I’m not sure what’s going to happen tomorrow, where suddenly the discussions on peaceful uses may be overshadowed by military uses and their implications.”

Space Force? Space Guard?

Creating another branch of the military isn’t as simple as ordering it into existence. The military can (and has) started studying the issue, and plans to have a report on the subject ready in August. But to formally create a new branch of the military requires congressional action.

Trump said on Monday that the Space Force and Air Force would be ‘separate but equal.’ It remains unclear as to how the new military branch will fit into established space exploration efforts.

The idea of a military force dedicated to space has surfaced before, but never got very far. Last year, the Pentagon actively opposed a house bill to create a ‘Space Corps’, citing a risk of increased bureaucracy. The Pentagon pushed for more integrated services instead of a new, separate branch.

And there’s still a lot of disagreement over how the mission of a military branch dedicated to space would be shaped. Would it be an active defensive force, like the Air Force, or would it be something like the Marine Corps? Or would it be something else entirely? One of the ideas that has gained the most traction in recent years is a military group that most similar to the Coast Guard.

Lt. Col. Cynthia A. S. McKinley coined the concept of a Space Guard in an essay published in 2000. Since then, others have elaborated and built on the idea, which proponents say might be focused less on defense, and therefore might be less likely to trigger an arms race with rivals.

High Street or Battlefield

How people view the idea of a Space Force also has a lot to do with how we view space. Do we still have a Cold War vision of space as a purely strategic domain? Is it a free market paradise over our heads, where commerce is the main concern? Or is it something different, a mixture of the two? For the past decade or so, commerce has been winning this new space race.

“The more that outer space becomes a domain of commerce and peaceful uses and scientific endeavors, the more it becomes high street of commerce, the more it becomes a laboratory, the more difficult it will be to justify the belief that space is a battlefield,” Johnson says.

Not everyone shares that view.

“Space is a warfighting domain, so it is vital that our military maintains its dominance and competitive advantage in that domain,” an official in the Joint Chiefs of Staff office said. “The Joint Staff will work closely with the Office of the Secretary of Defense, other DoD stakeholders, and the Congress to implement the President’s guidance.”

Currently, there is no guidance for how a war or armed conflict might happen in space, and we have no idea what space as a “warfighting domain” might look like. While there are laws of armed conflict developed over the centuries governing the land, sea, and skies, space is a giant question mark.

“In the space domain we don’t know what the rules are. Literally, we do not have any conventions or rules for conflict in space,” Johnson says. “The international community has no textual instruments telling us how war can be lawfully conducted in space, and we don’t have any state practice on it either. We’ve never seen conflict in space.”

We might not have seen conflict in space yet, but there are people thinking about it. Johnson and other lawyers are focused on figuring out what that conflict might look like, and what the limits on it might be based on what is already established in international law. At McGill, lawyers analyze international law and the law of armed conflict in a project called Manual on International Law Applicable to Military Uses of Outer Space. The UN is actively working on developing international agreements that might help prevent an arms race in space—activities that suddenly seem more pressing to the parties involved.

“The announcement of a Space Force, if it actually happens, is going to be very escalatory and quite threatening. Other nations will look at it and go ‘oh, I need that too.’ It ratchets up the tension for outer space,” Johnson says. “If you lived somewhere in a peaceful neighborhood and you suddenly saw that your neighbor was amassing weapons and training to fight a war and making all these actions which were in preparation for conflict, you would think, ‘oh, they’re preparing for conflict. Maybe I should prepare, too.’ It makes conflict in space—which was not inevitable—it makes it more likely.”

A version of this article was originally published on June 18. It has been updated.