Call it cool or just plain creepy: Memory researchers from U.S. and Japan have, for the first time, implanted false memories into a lab animal.

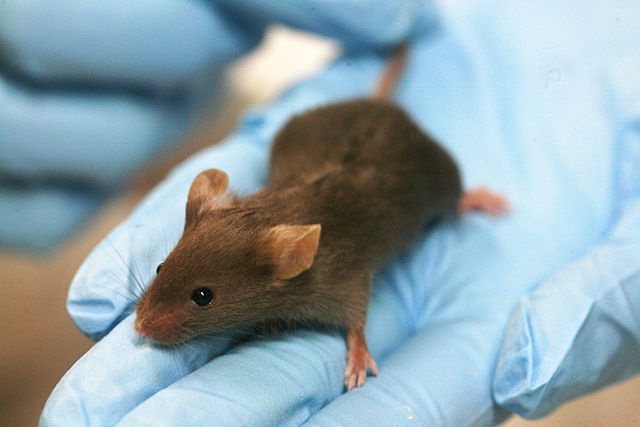

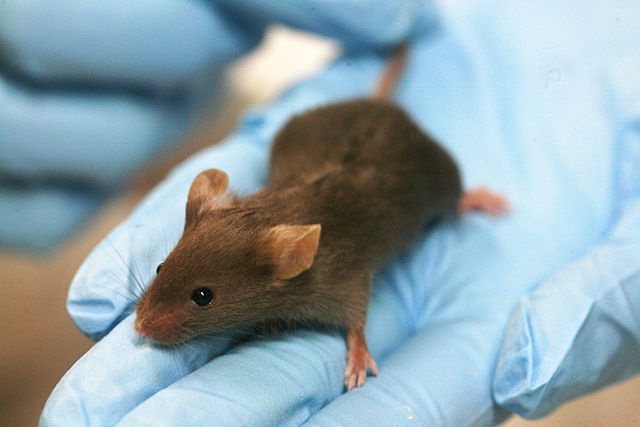

The researchers made mice believe that they had once received electrical shocks in their feet while sitting in a certain little chamber, even though that had never happened. Thereafter, whenever the researchers put the mice in that chamber, the mice would freeze up in a typical mouse response to fear.

It’s already clear that people are able to form false memories. Think about that family tale about your getting sick at Disneyland—the one that’s been told so often, you’ve felt yourself “remember” the event more and more over the years, even though you were way too young to truly recall it. Or, more seriously, think about how often eyewitness testimony fails, convicting people who are later exonerated through DNA testing.

“So this false memory is a serious social problem,” Susumu Tonegawa, a biologist at MIT and the lead researcher in the new mouse study, tells Popular Science. (You may recognize Tonegawa’s name because he won a Nobel Prize in 1987 for research into the immune system.) “False memory in a human,” Tonegawa clarifies.

So what’s the good of putting false memories in mice? Having a technique to do this could help other scientists study false memories more in depth, using mice, Tonegawa says. In the future, such studies could lead to a better understanding of how false memories form in people. Meanwhile, Tonegawa and his colleagues have already used their mice to discover one thing. On the molecular level, false memories in mice look a lot like real ones.

“They are really similar in terms of underlying mechanisms,” he says. “So it’s not surprising in humans when some of them insist false memories are true.”

Other researchers previously created 10-second artificial memories in mouse brain cells grown in a test tube. Another team also made false hybrid memories in living mice. Tonegawa’s team’s research took another step forward by apparently creating a whole new memory of danger in a chamber where mice had never received shocks.

To make their fake mouse memories, Tonegawa and his team relied on two previous bits of research, one of them their own. The first was optogenetics, a way of tinkering with mouse genetics so that some of a mouse’s brain cells are sensitive to laser light. The second was research Tonegawa’s lab published in 2012, showing that they were able to use optogenetics to stimulate a packet of brain cells associated with one memory in mice.

This time, the team put mice in a chamber, very creatively named “Context A.” You can also think of Context A as the Safe Room. Context A had a particular shape, smell and lighting. The researchers took note of what cells in the mice’s brains were associated with exploring Context A.

Then they put the mice in different chamber, Context B, that had a different shape, smell and lighting. They gave the mice electric shocks in their feet while they were hanging out in Context B. (So Context B is the Danger Room.) At the same time, the researchers also used laser light to stimulate the brain cells associated with Context A, the Safe Room.

If you think this sounds like a recipe for some really messed up memories, you’d be right. Now, the mice would freeze in fear whenever researchers put them in Context A, even though they had never received shocks while in Context A. “The animal made a memory of something that did not actually happen,” Tonegawa says. And it wasn’t that the mice learned to fear chambers in general. When researchers put them in a new chamber, Context C, they didn’t freeze.

The team also performed further experiments that showed that the formation of true and false memories both set off a series of molecular changes in the brain that are very similar. So false memories may feel indistinguishable from real ones.

Tonegawa and his colleagues published their work today in the journal Science.