People are generally used to interacting with disembodied robotic voices in the form of Alexa or Siri, and in some cases, humans are actually confronted with real robots that attempt to have a conversation with them. But when that happens, will people trust the bots to tell them what to do?

The answer: probably not. It seems that most humans still don’t trust smart robots to tell them what to do, which is not all that surprising.

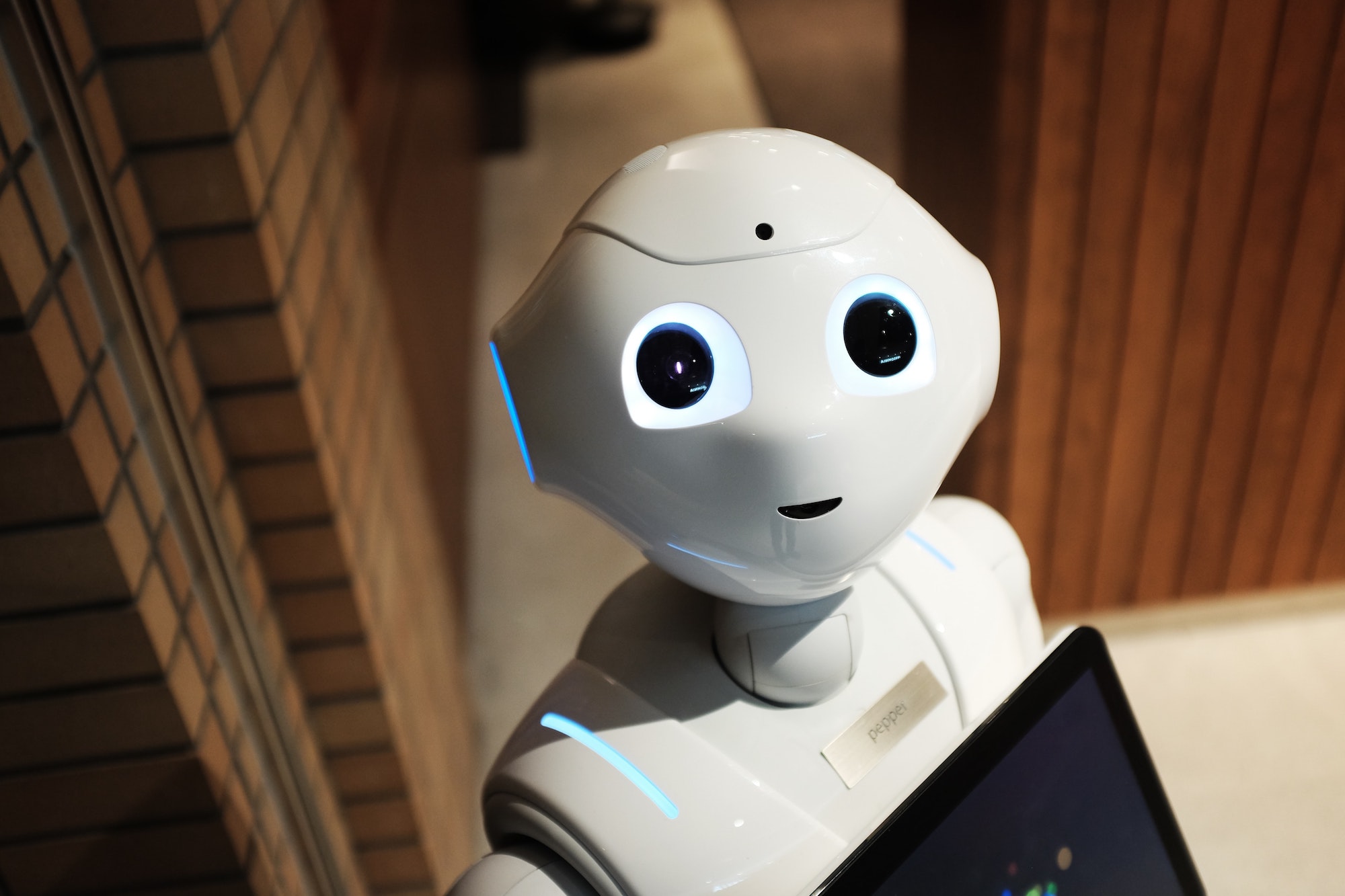

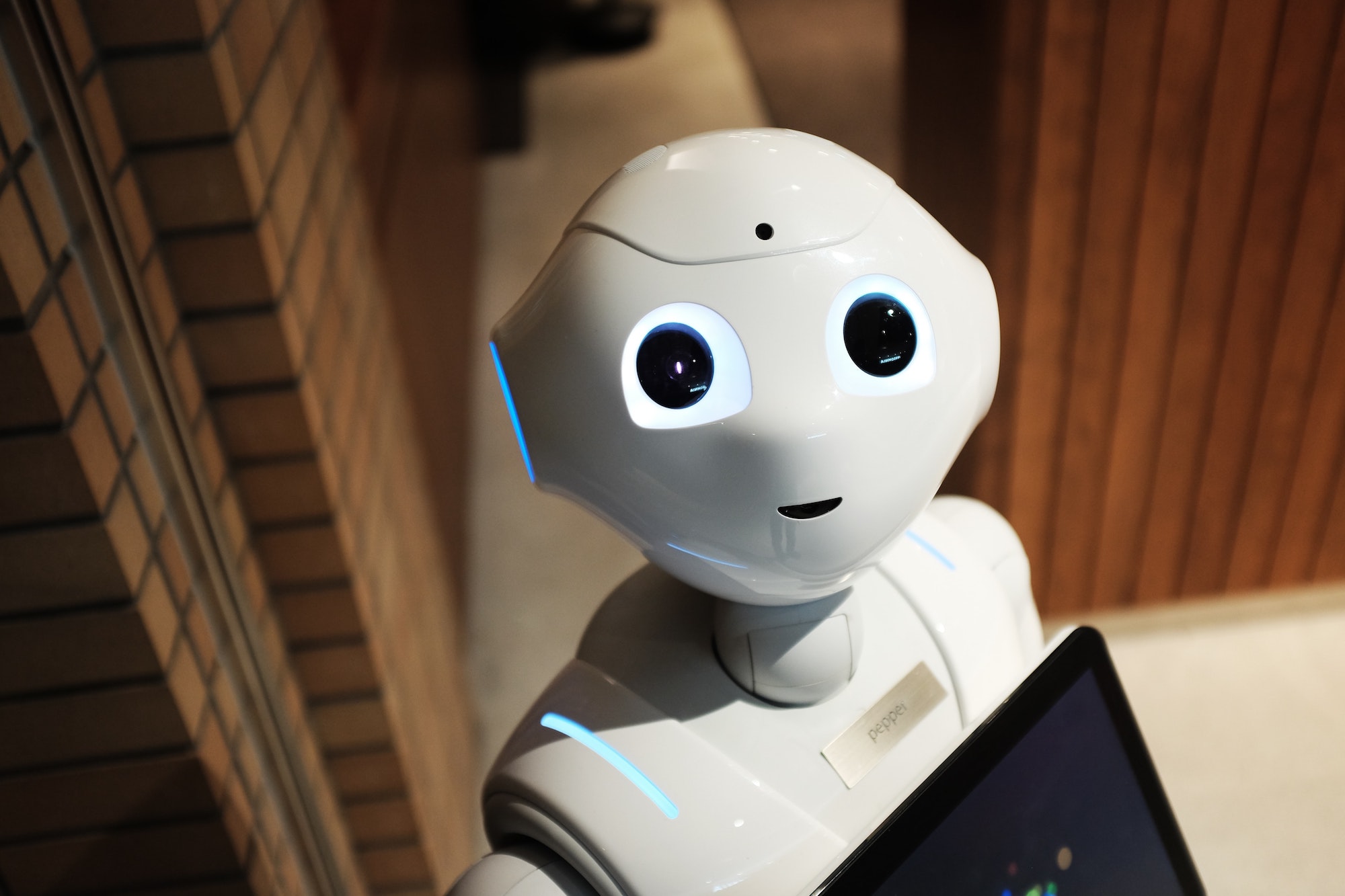

What’s more interesting is that it matters whether the robot is presented as the figure in charge or not. If there is another person in charge, and the robot is simply presented as an assistant to the human authority, then people are more likely to trust it for help. That’s what two researchers from the University of Toronto discovered when they tested 32 participants aged 18 to 41 using the SoftBank social robot, Pepper. Their results are published this week in Science Robotics.

Here’s how their zany test was conducted.

Would you let a robot help you?

The researchers set up two conditions, and assigned half of the participants to each one randomly.

One condition looked like this: the robot was framed as an authority figure because it was actually the experimenter itself. “I wasn’t even in the room,” says Shane Saunderson, a PhD candidate at the University of Toronto and an author on the study.

To enter the experiment room, a person would knock on the door. The robot, Pepper, who would be standing in the front of the room, would say “please come in,” and the person would open the door. The robot then says “thank you, feel free to close the door behind you and have a seat.”

“I was of course watching remotely from a camera, and this was one of my favorite moments from the study,” says Saunderson. “I would watch these people come in, look around, and go ‘where’s the person, what’s going on here?’ And for the first 30 seconds to 2 minutes, most people would be visibly uncomfortable because they’re not used to having a robot in charge.”

In the second condition, Saunderson was the lead experimenter, and he told the participants that Pepper was just here to help.

The team took two types of measurements for both conditions. They had an objective measurement where the researchers assigned basic memory tasks and puzzles that the participants had to solve. “They were hard enough that people might look to outside influence when they were looking at the question,” says Saunderson. “We had them give an initial answer, then the robot would give a suggestion, and then they would be able to give a final answer.”

Afterwards, the researchers measured how much the robot influenced the participants’ second answer, compared to their first. They also asked participants to fill out surveys on what they thought about the robot, and whether they viewed it as authoritative.

“We believed an authoritative robot compared to a peer robot would be more persuasive. That is typically what you see in human-to-human interactions,” Saunderson says. “In our study, we found the opposite, that a peer-framed robot was actually more persuasive.” Participants were more willing to take its advice.

Shocking but true: People seem to dislike the idea of a robot overlord

Saunderson turned to the literature to find an explanation for this behavior. What he discovered was that part of being an effective authority figure is having legitimacy.

“We have to believe that that thing is a legitimate authority, otherwise we’re not going to want to play along with it,” he says. “Usually, that comes down to two things. One, it’s a sense of shared identity. So, we need to feel that we have things in common and we’re working towards some of the same goals. Number two, I have to trust that person enough to believe that we can achieve that common goal.”

For example, if a student who wants to learn believes that the teacher is trying to teach them, then they share the same goal. But additionally, the student has to trust the teacher to do a good job in order to actually view them as an authority figure.

So, what went wrong with Pepper? Saunderson thinks that first, the sense of shared identity was not really there. “It’s not a human. It’s a bag of wires and bolts. People might struggle to say ‘You and I are the same, you’re a legitimate authority figure,’” he says. Then, from a relational perspective, most people in the experiment were being introduced to a social robot for possibly the first time.

“They don’t have any rapport or historical connection to the robot. You can see how that can cause a problem with them developing a sense of trust with it,” he adds.

To Saunderson, the most surprising part of the study was that there seemed to be a significant difference between how women and men responded to Pepper being in charge. “Historically, in all of our studies and the studies I’ve seen, when you have a robot interacting and you’re measuring things like persuasion or trust or things like that, there’s not really a difference between men and women,” he says.

In this study, the peer robot was equally persuasive for men and women—around 60 percent persuasive. However, men were more reluctant to trust the authority robot compared to women. Pepper only persuaded around 25 percent of men and around 45 percent of women in that scenario.

“We actually found a review paper that had surveyed 70 different studies that found that men tend to be more defiant towards authority figures. This is kind of one of those strange weird things. Maybe the male ego doesn’t like the idea of having someone above them,” Saunderson says. “Does that mean the robot was able to sort of intimidate or make the guy feel uncomfortable such that they felt the need to exert their own autonomy? This is a bit speculative, but if we go by those results, that means the men in our study were theoretically feeling threatened by a robotic authority figure.”

According to Saunderson, these results don’t necessarily mean that robots can’t ever be in leadership or manager roles. However, humans need to be conscious of the role that the robot is put into, and tailor the design of the robot and its behaviors to a specific situation. And if it’s in an authority role for example, the robot probably has to be more of a peer-based leader that offers support to make other people’s jobs better instead of being the aggressive, cold, do-what-I-say-or-else type of boss. You can imagine that we may be more likely to accept a helpful C-3PO than a bossy T-1000.

[Related: Tesla wants to make humanoid robots. Here’s their competition.]

“And if it’s other social roles, then equally, we want to understand the context of how people feel about that robot in that type of social role in order to make it a good experience,” he says.

Despite their hesitation, most people in the authority condition did what the robot told them to do by the end of the study, and changed their answers according to its hints; and all participants finished the study.

The art of robot persuasion

This study is part of a larger question that Saunderson has been investigating throughout his PhD, which is: How is it that you can make a robot persuasive? For background, he read about human behavior, psychology, and persuasion, digging into literature from the late 1900s.

The textbook definition of persuasion is the act of trying to change someone’s attitudes or beliefs about something. Psychology literature further deconstructed the components of persuasion, which he then transposed onto robots. “So if I’m trying to persuade you,” he asks, “what is it about how I speak to you, about my appearance, about strategies I use or things that I offer?”

He adds that persuasion is a two-way street, and the motivations and personalities of the other person can also factor into the persuasion strategy. “Are you skeptical of me? Do you want to be persuaded? Are you more persuaded by an emotional argument or a logical argument? Those are all things that need to be considered.”

A previous study Saunderson ran looked at the different types of persuasive strategies that a robot could use. He observed that emotional strategies were the most effective. That’s when the robot says, “I’ll be happy if you do this,” or “I’ll be sad if you don’t help me with this,” versus a rational strategy, like saying, “I can count perfectly, so this is the answer.”

When the robot voiced statements laced with emotions, even though participants recognized that the robot didn’t actually have those feelings, they were still more likely to help it out.

[Related: The world uses one emoji more than all others. Here’s why.]

“I think it really speaks to this amazing and innate need that human beings have for social connection. This need for belongingness that says we need people in our lives, or at least, social interaction,” he says. “While I think robots are still early in terms of their maturity and development as social partners and companions, I think they can play a role to fill in the social connection that we have with other people.”

The rise of social robots and the changing nature of human-machine interactions

So what exactly is a social robot? Goldie Nejat, a professor of mechanical engineering at University of Toronto, and a co-author on the same Science Robotics study, explains that it is an interactive robot that engages and communicates with people, whether it’s through something as simple as guiding everyday activities and tasks.

“Social robots are helping people, whether they’re providing companionship, or assistance,” she says. “They’re interactive in the sense that they have expressions, facial expressions, body language, they have speech and also can understand speech and react to people’s emotions and movements.”

These robots can come in many forms, from animal-like to human-like. Their forms, of course, influence the type of interactions that they’re going to have with people. But with these robots, providing something as simple as touch can allow humans to form a connection with them. During the pandemic, social robotic pets provided a peculiar type of salve for loneliness in the isolated elderly, reported The New Yorker.

In the evolution of computers and robots, social robots have branched off to become something that’s not just purely functional or physical operations-oriented. “That’s where robotics has been more defined,” says Saunderson “Something that’s welding machines together, or moving things around, or a self-driving car.” A social robot learns about their interactions and their environments to better improve their abilities to explore and find people, interact with people in all types of applications including healthcare, retail, and even food service.

[Related: Meat vending machines are just the latest way the pandemic has reinvented eating]

Studies into social human-robot interactions were first born out of human-computer interactions, which kicked off in the 70s and 80s. After computers started becoming more commonplace in the home and in workplaces, people realized that they were actually playing an important role in social mediation, and that technology affected the way we interacted with each other.

How human-computer interactions played out leaned heavily on interface design, says Nejat. That meant the interface designs had to be engaging and keep people engaged in whatever they were doing with the computer. The same considerations for engaging design were then reformatted onto social robots.

“There’s some weird effects that already happen when you’re interacting over a computer versus when you’re interacting with a robot that has a face that can show facial expressions and body expressions,” says Saunderson. “It starts to blur the line between something that is purely a piece or technology, and something that we actually treat kind of socially, like you would a person.”

There’s been some success and some hurdles with this type of research. One of the challenges is that some people seem unwilling to admit that they need help, especially from a robot.

“We’ve seen that a lot with older adults for example, when we take robotics technology in like long-term care homes or hospitals or even their private homes, and we say the robot is here to help you,” says Nejat. “We see that they engage in the interaction and comply with all the robot’s requests, and everything goes really well. And we ask them questions about how they felt, their overall experience, and they usually say ‘I enjoyed it, but the robot’s not for me.’”

Nejat sees a disconnect there, as does Saunderson. “It may be their own personal views of the use of technology. Because sometimes when you rely on technology, especially in certain demographics, it means that you’re not able to do the task independently,” she says. “And nobody wants to say they can’t do the task anymore on their own.”

However, she’s hopeful that the robots will grow on us. There have been experiments, Nejat says, where humans fluidly mimicked robot expressions, or reciprocated an emotion the robot projected. Mimicry is a key feature in human-to-human social interactions. So, to see a person smile when a robot smiles, or wave back to it, it’s “a nice imagery to have,” she says, and it “gives us a new perspective on how we can use these robots.”