The sci-fi dream of owning your own home robot isn’t just a possibility anymore—it’s an eventuality. The first wave of home robots is already upon us with the Amazon Echo, and the coming Google Home. While these barebones bots can take simple commands, they can’t really add anything to the conversation or scoot around your home.

That’s what the makers of Jibo are trying to create—a robot that can initiate conversation to complete tasks in the home—and they’re tapping some of the world’s foremost A.I. researchers to do it.

Today, Jibo Inc. announces that its adding veteran researcher Michael I. Jordan to its advisory board. Jordan has been ranked as the most influential computer science researcher by the Allen Institute for Artificial Intelligence, and carries the superlative of “the Michael Jordan of machine learning,” both literally and figuratively.

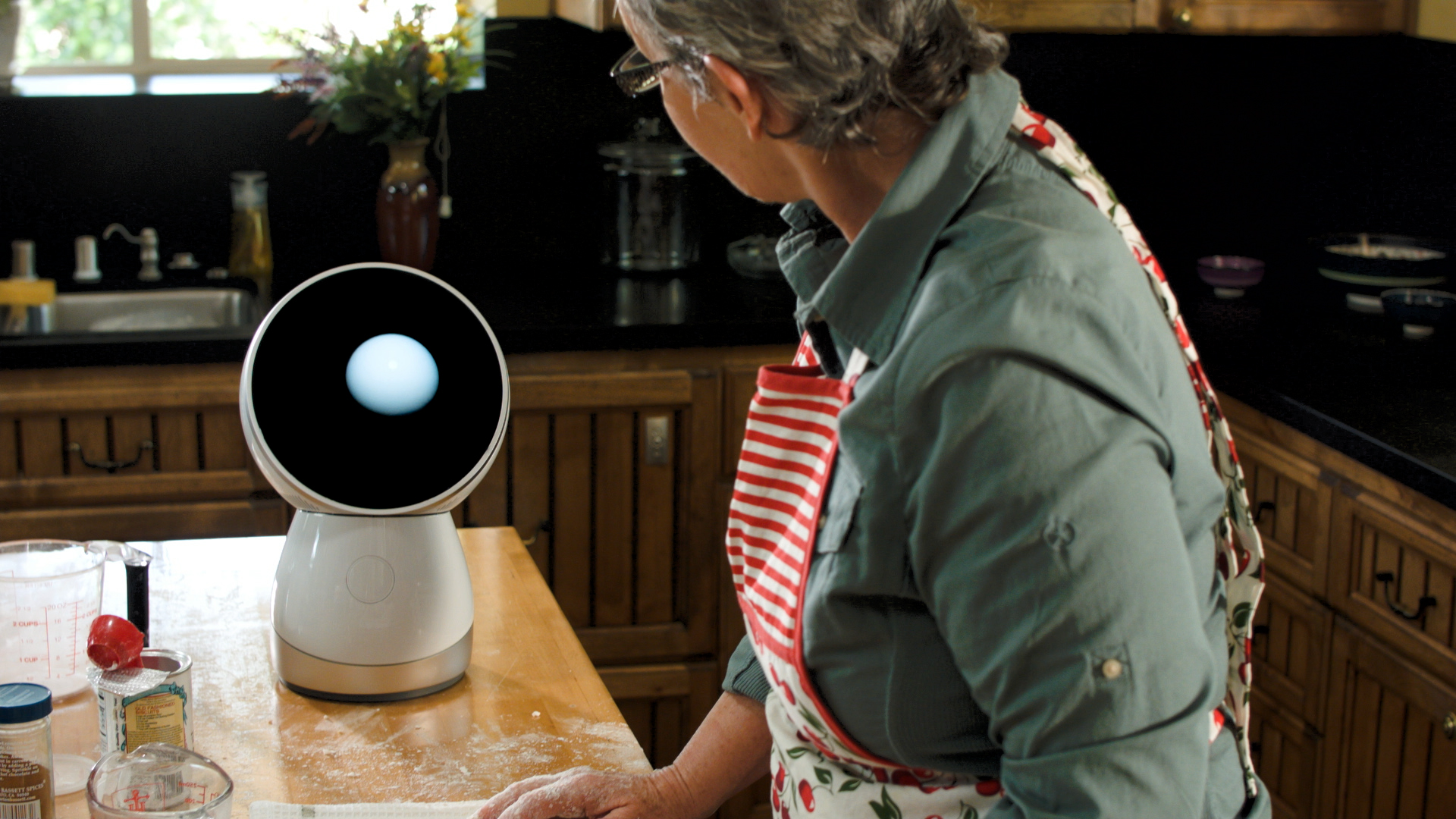

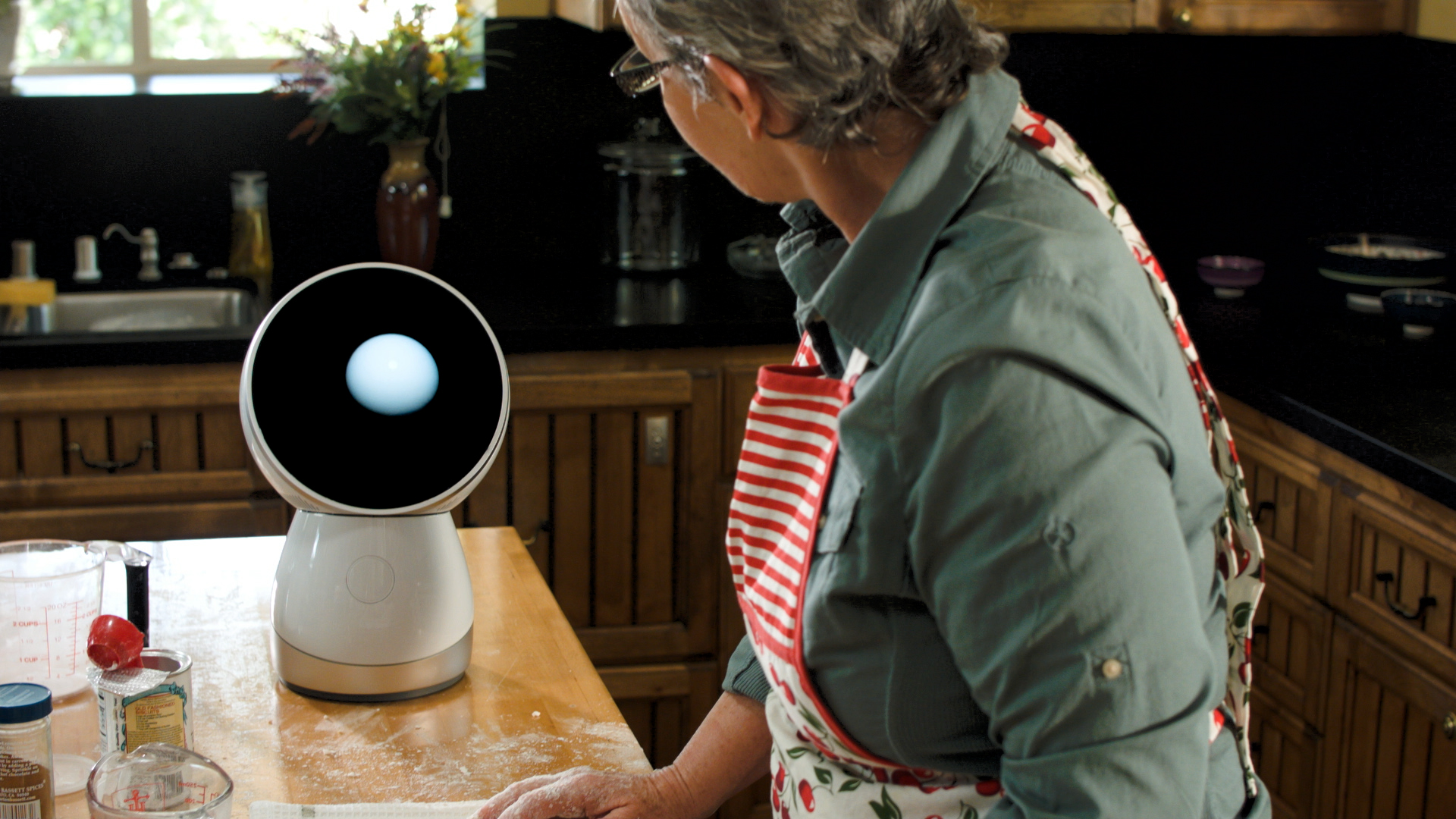

Jibo’s first product is a little stationary bot named, of course, “Jibo.” It’s meant to sit on a kitchen counter and talk to you about the weather, or display a recipe on its screen when you prompt it.

Jordan sits on a few of these advisory boards already, mainly for software systems, but said that Jibo’s potential as a research tool to accelerate A.I. research is what drew him to the company.

Since Jibo only needs to actively learn about very specific topics, like its owners and surroundings in the home, the research can be very targeted specifically towards making those conversations better. It’s a bot that doesn’t sell you flowers and can’t natively call you a ride (although 3rd party developers can make it capable of that) It’s just a bot that has conversations and answers questions.

“A.I. doesn’t really have a platform on which to develop these next level of interactive skills, this next level of intelligence, this next level of personalization,” Jordan said. “Jibo is fantastically suited to both driving and profiting from the next wave of A.I. research.”

Jordan thinks of artificial intelligence as a more abstract concept, beginning with the explosion of popularity in Google’s initial search engine. Google built this vast network of information, but it was objective—it looked the same to everyone. We could tap into this intelligence out there, but it wasn’t bringing anything to the user itself.

The next step, beginning about 10 years ago according to Jordan, was personalization. Services could begin to track what users liked and disliked to better tailor results. That’s where we are today, with smarter services like Google Now.

Jordan says the next frontier of A.I.-powered robots is context. Context is the ability to remember past conversations and pick them up later, or understand when a piece of specific information is relevant again. Humans do this all the time, but it’s so natural we don’t need to think about it. You ask how your landlord’s dance recital went last week, or remember that a friend won their bowling championship and congratulate them.

But making robots do this isn’t an easy task. Researchers are just now starting to incorporate memory into artificial intelligence algorithms, making them read and understand children’s stories.

And to kick-off our conversation, Jordan proclaimed that there’s way too much hype in A.I. It’s a bold claim coming from someone who just joined a company making “the world’s first social robot.”

When I suggest this, he laughs, saying that Jibo isn’t going to be the end goal, but a platform to launch from. It’s a journey that will likely take hundreds of years, Jordan says. But right now, he thinks we can tackle the low-hanging fruit.

Jibo is an important product in home robotics. Unlike any robot on the market today, it has cameras backed by powerful machine learning algorithms that identify and track people around their home, and costs $750 dollars on preorder. (The preorders are full now, but you can join the waitlist.)

Jibo’s main competition is Pepper, a social robot that isn’t yet meant for the home, carries a price tag ranging from $2000 to $34,000, and is sold only in Japan. However, Pepper has wheels to putter around places like hospitals, its first use case.

But as always, privacy is the product’s looming spectre. More than anything, Jibo is a test of whether consumers in 2016 are comfortable with a robot watching them.

Jibo was designed with a bunch of privacy commands: users can tell Jibo to turn around when they’re changing, or temporarily shut it off during a private conversation. Jibo checks all the privacy boxes—when Jibo calls to the web for information it’s encrypted, and users need to opt in for their interaction data to be cut up, anonymized, and sent back to Jibo HQ to make better Jibo software in the future.

For those who do opt in, Jordan sees this as a big opportunity to figure out how to make machines better talk to humans, not just achieve simple tasks.

“It’s not learning in the sense that ‘there’s a cat in this image,’ but learning in a real sense, how humans learn,” Jordan says.