To mark our 150th year, we’re revisiting the Popular Science stories (both hits and misses) that helped define scientific progress, understanding, and innovation—with an added hint of modern context. Explore the entire From the Archives series and check out all our anniversary coverage here.

When Jacques Cousteau penned a story for Popular Science in February 1969, NASA was months away from crossing 240,000 miles of space to land a man on the moon, but marine technology was barely capable of sustained underwater exploration. To many, Cousteau, a French naval officer during WWII, is remembered for his nearly decade-long TV series, The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau, which broadcast into millions of homes the wonders of ocean life and exposed the devastation of human activity. But Cousteau was also an inventor, whose contribution to marine-exploration technology equaled his devotion to marine conservation. The latter profited from the former, beginning with his invention of scuba (self-contained underwater breathing apparatus) in 1943. His Diving Saucer, which debuted in 1959, set the standard for nimble underwater exploration subs.

In his 1969 Popular Science story, Cousteau proudly describes his many vessels and sensors—all customized, including his beloved ship Calypso. The story centers on Sea Fleas, “tiny subs” fitted with “jet propulsion” and “side nozzles” for “extreme maneuverability.” Cousteau’s narrative reveals not only his love of invention and the sea, but also sexist social conventions. “Practice makes [Sea Fleas] easy to handle,” he writes, “though at first I found them a bit like women—seductive and unpredictable.”

Despite considerable technological advances since the 1960s, even today Earthlings have mapped more surface area on Mars and the moon than Earth’s ocean floor, which is remarkable considering that the ocean is one vast, contiguous, surface feature that dominates earthly life and livelihood. Led by Cousteau’s extraordinary example, however, the siren call of Earth’s oceans continues to inspire explorers and documentarians like Sylvia Earle, James Cameron, and Victor Vescovo. Today, we can dive even to the deepest reaches of our planet, but can we save them?

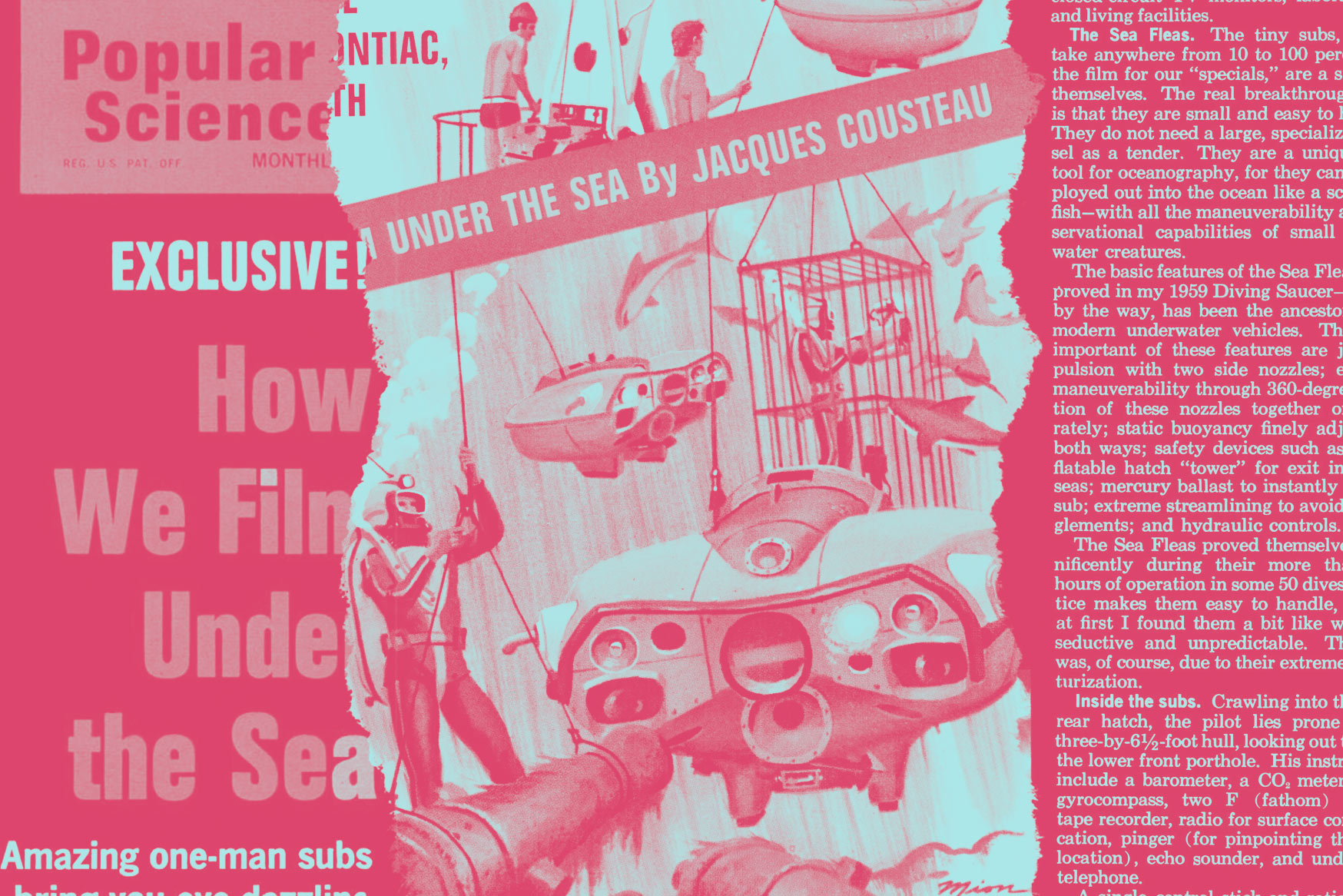

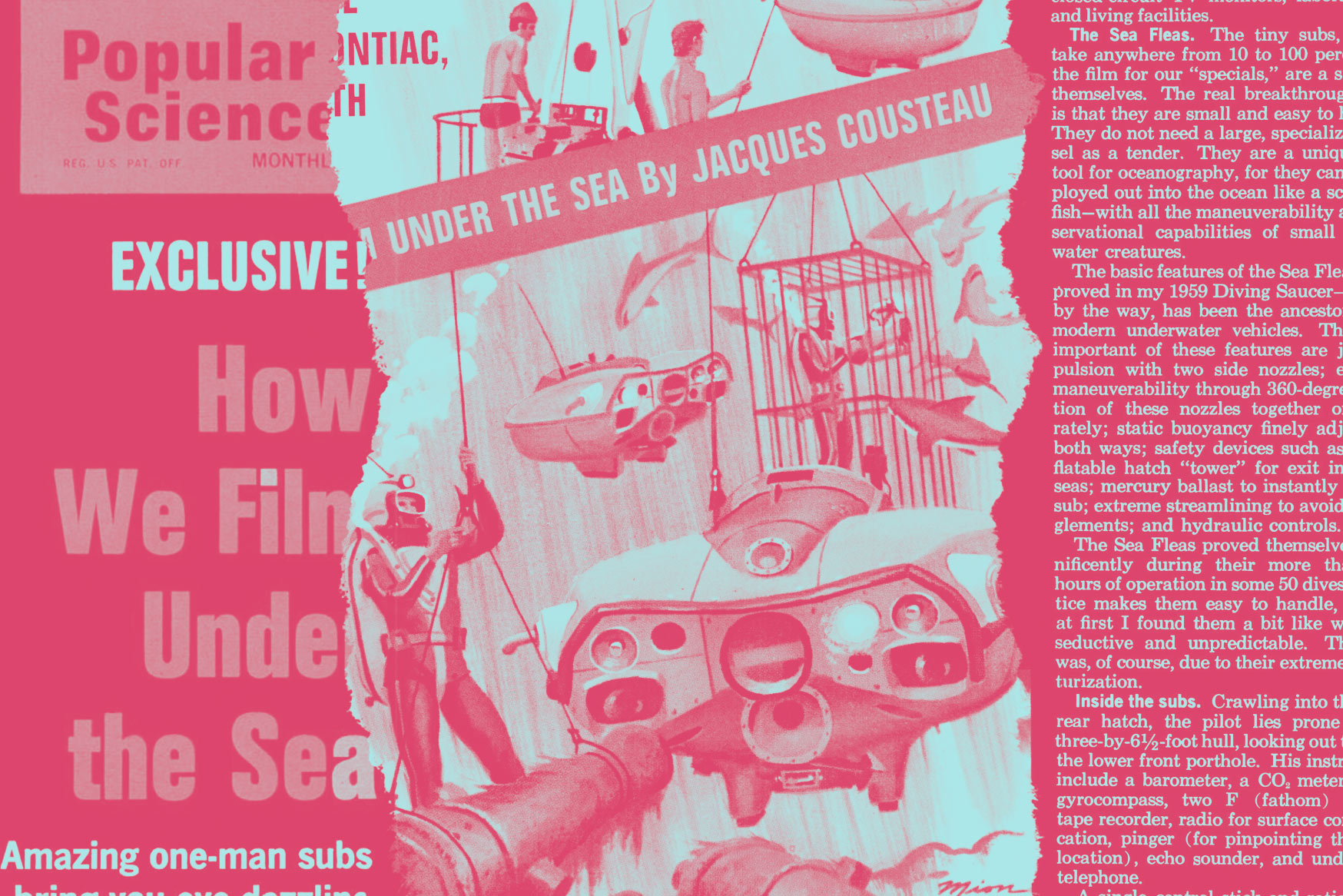

“How we film under the sea: Amazing one-man subs bring you eye-dazzling pictures from the deep” (Jacques Cousteau, February 1969)

How do you convey to the people of the world the magnificent vistas that lie beneath the ocean? I have a life-long love of it, and of adventure; and a few years ago we were given the opportunity to communicate this love, this source of inspiration, to the public via the medium of television.

By now our programs [“The Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau,” ABC-TV], produced by myself and Alan Landsburg, Metromedia Producers, have been seen by millions. Aided by my best team of divers and other underwater experts we have tried to show the viewer the strange and wonderful forms of life that exist in the ocean and the enormous natural riches it contains. We have tried to communicate some of the excitement we feel at being among the first to explore man’s last great frontier on earth.

Tools for exploring

Not the least of my reasons for embarking on this great adventure is the fact that fascinating, if expensive, new tools are now available to help us capture some of the wonders of the ocean on film.

Among the main ones are our pair of tiny one-man submarines, which we have dubbed the “Sea Fleas.” Before explaining how they work, a few other items: Our color-movie cameras (two are carried by each submarine) were engineered by us and contain special optics. They are usually operated as handheld units by our scuba divers.

The scuba gear was also designed by us. Each outfit contains a helmet radio transmitter for the diver to communicate with our ship, the Calypso, when he surfaces. Other features include a sonar transmitter for underwater communication between individual divers and between divers and the ship. The outfits have built-in lights, compasses, an emergency signal that can be heard a mile away, and emergency signal rockets. Last but not least is a shark billy to push the sharks away when they are too many.

The Calypso herself is worthy of mention. A former minesweeper which we first outfitted for oceanography in 1950, she includes such things as a built-in underwater observation station in her bow, closed-circuit TV monitors, laboratories, and living facilities.

The Sea Fleas

The tiny subs, which take anywhere from 10 to 100 percent of the film for our “specials,” are a story in themselves. The real breakthrough here is that they are small and easy to handle. They do not need a large, specialized vessel as a tender. They are a unique new tool for oceanography, for they can be deployed out into the ocean like a school of fish—with all the maneuverability and observational capabilities of small underwater creatures.’

The basic features of the Sea Fleas were proved in my 1959 Diving Saucer—which, by the way, has been the ancestor of all modern underwater vehicles. The most important of these features are jet propulsion with two side nozzles; extreme maneuverability through 360-degree rotation of these nozzles together or separately; static buoyancy finely adjustable both ways; safety devices such as an inflatable hatch “tower” for exit in heavy seas; mercury ballast to instantly tilt the sub; extreme streamlining to avoid entanglements; and hydraulic controls.

The Sea Fleas proved themselves magnificently during their more than 100 hours of operation in some 50 dives. Practice makes them easy to handle, though at first I found them a bit like women—seductive and unpredictable. This last was, of course, due to their extreme miniaturization.

Inside the subs

Crawling into the sub’s rear hatch, the pilot lies prone in the three-by-6½-foot hull, looking out through the lower front porthole. His instruments include a barometer, a CO2 meter, clock, gyrocompass, two F (fathom) meters, tape recorder, radio for surface communication, pinger (for pinpointing the sub’s location), echo sounder, and underwater telephone.

A single control stick and rationalized controls make it easy for the operator to be both pilot and observer. The control stick takes the sub up, down, forward, back, or sideways. When it is moved from port to starboard, it controls the rudder. Back-and-forth movement activates the mercury trim system. The stick also holds switches for the propulsion pump motor, camera, and lights. As you can see, our pilot easily becomes a camera man, working in perfect harmony with the sub to record anything of interest that he sees in the ocean depths.

Cameras, lights, action

Energy for the Sea Fleas comes from 62 two-volt lead-acid cells in four battery boxes beneath the outside fiberglass covers. These are open to sea pressure and are simply topped with oil. In addition to powering the two-hp. propulsion motor and the instruments, the batteries provide light for sailing and for photography.

Looking like giant eyes, three 750-watt iodine lamps mounted in the front of the sub give enough light for color pictures. Any two lights are used at a time, illuminating the ocean depths for either of the two movie cameras mounted below them. They make good pictures possible at ranges up to 20 feet in clear water. Two other lights are also used: a 150-watt searchlight for sailing and a 60-watt lamp to light the ocean bottom.

Diving the subs

With the pilot in the sub and the hatch tightly closed, the small two-ton vessel is swung over the stern of the Calypso by a winch. A scuba diver rides down with the sub to free the line when it is in the water. A 55-pound weight carries the Sea Flea to the bottom and is then dropped. To pinpoint buoyancy, the pilot can then admit up to 44 pounds of water into a ballast tank or drop, individually, a number of the small two-pound weights carried for this purpose.

The mercury trim system instantly adjusts the sub’s longitudinal angle. This works by shifting 143 pounds of mercury between the front of the sub and the back. To surface, a “standard” 44-pound weight is dropped. In an emergency, this can be supplemented by dropping the mercury and another 110-pound safety weight. The Sea Fleas carry a tank of oxygen adequate for 20 hours underwater. A special compound absorbs the pilot’s exhaled carbon dioxide. The barometer provides a convenient means of monitoring pressure. As oxygen content drops, it is replenished from the supply tank.

The Sea Fleas are not limited to photography. They can mount a mechanical arm and claw for bringing back biological and geological samples from the bottom. Small as they are, my tiny subs are helping to test principles we will use in future submersibles. Built at a cost of $750,000 by Sud Aviation and in operation for over a year, they are the forerunners of go-anywhere underwater vehicles that will use fuel cells for unlimited range and mobility.

During my active life I have lived with the sea and in the sea. I have accumulated a great many feelings and impressions, things that I would like to communicate to make you understand why our work has been worthwhile, and why we must continue our research and exploration. It is my hope that, before I am relegated to a desk as the elderly director of an institute, I may continue to do so.

Some text has been edited to match contemporary standards and style.