Quantum researchers at Ford have just published a new preprint study that modeled crucial electric vehicle (EV) battery materials using a quantum computer. While the results don’t reveal anything new about lithium-ion batteries, they demonstrate how more powerful quantum computers could be used to accurately simulate complex chemical reactions in the future.

In order to discover and test new materials with computers, researchers have to break up the process into many separate calculations: One set for all the relevant properties of each single molecule, another for how these properties are affected by the smallest environmental changes like fluctuating temperatures, another for all the possible ways any two molecules can interact together, and on and on. Even something that sounds simple like two hydrogen molecules bonding requires incredibly deep calculations.

But developing materials using computers has a huge advantage: the researchers don’t have to perform every possible experiment physically which can be incredibly time consuming. Tools like AI and machine learning have been able to speed up the research process for developing novel materials, but quantum computing offers the potential to make it even faster. For EVs, finding better materials could lead to longer lasting, faster charging, more powerful batteries.

Traditional computers use binary bits—which can be a zero or a one—to perform all their calculations. While they are capable of incredible things, there are some problems like highly accurate molecular modeling that they just don’t have the power to handle—and because of the kinds of calculations involved, possibly never will. Once researchers model more than a few atoms, the computations become too big and time-consuming so they have to rely on approximations which reduce the accuracy of the simulation.

Instead of regular bits, quantum computers use qubits that can be a zero, a one, or both at the same time. Qubits can also be entangled, rotated, and manipulated in other wild quantum ways to carry more information. This gives them the power to solve problems that are intractable with traditional computers—including accurately modeling molecular reactions. Plus, molecules are quantum by nature, and therefore map more accurately onto qubits, which are represented as waveforms.

Unfortunately, a lot of this is still theoretical. Quantum computers aren’t yet powerful enough or reliable enough to be widely commercially viable. There’s also a knowledge gap—because quantum computers operate in a completely different way to traditional computers, researchers still need to learn how best to employ them.

[Related: Scientists use quantum computing to create glass that cuts the need for AC by a third]

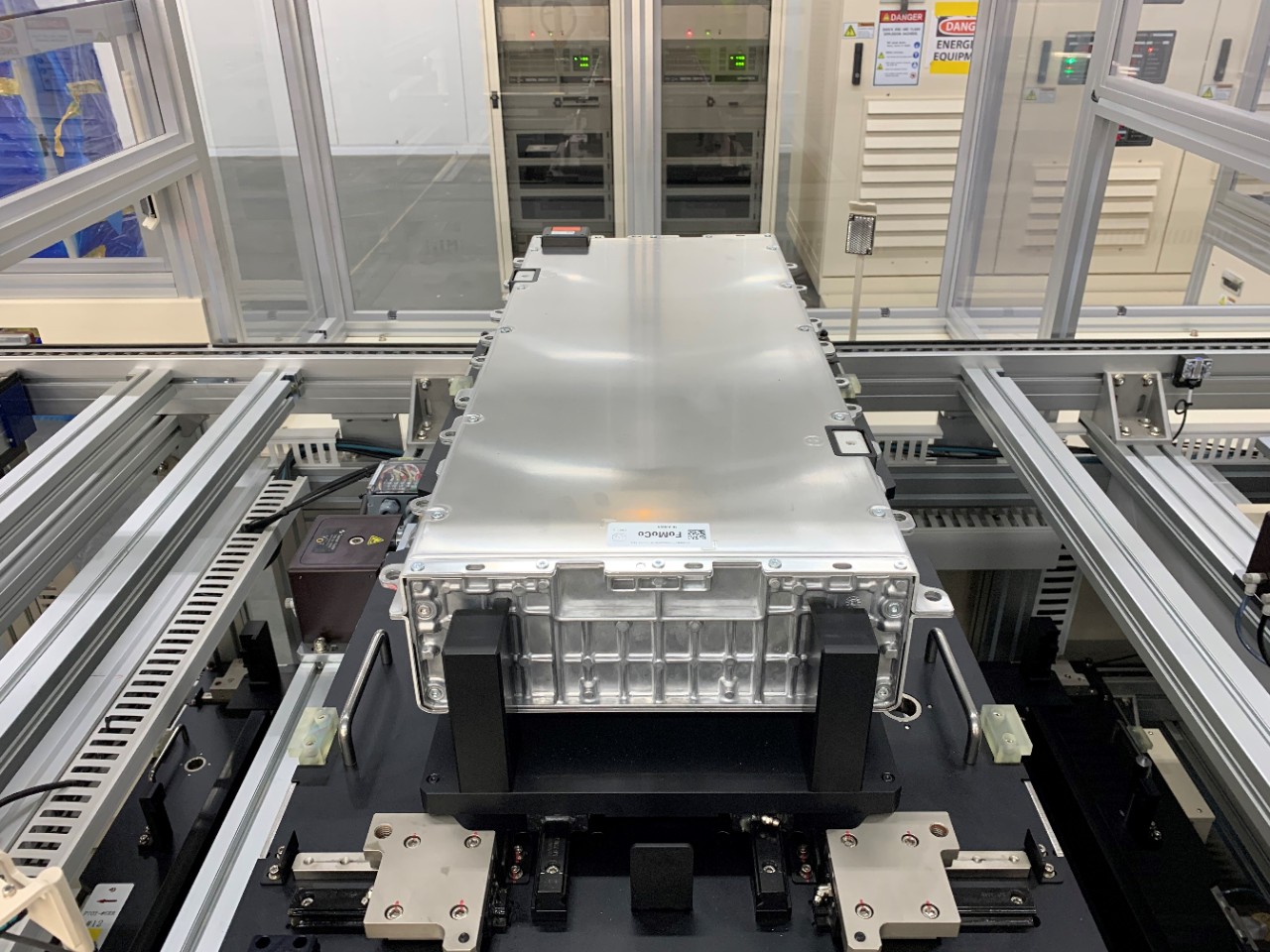

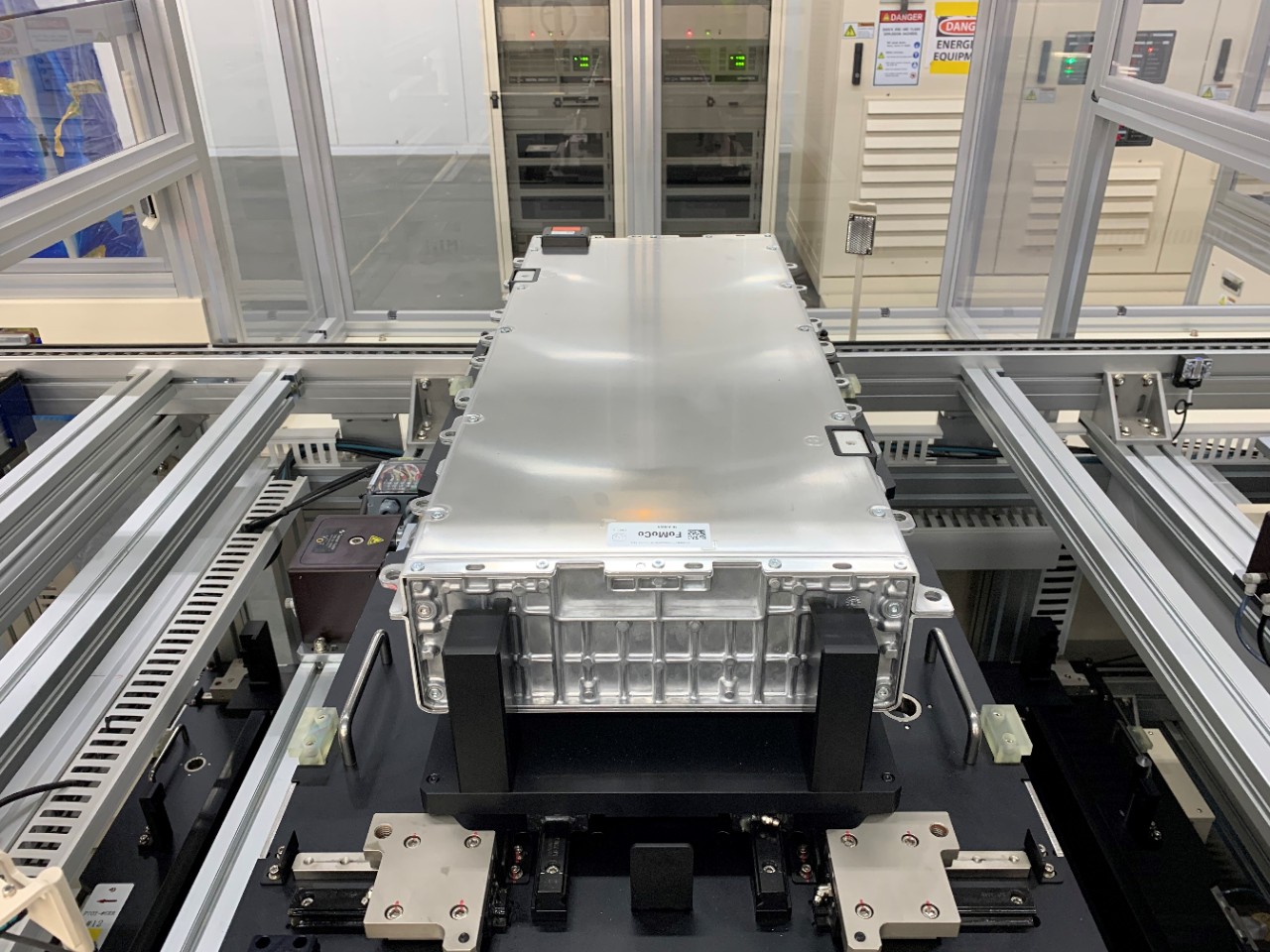

This is where Ford’s research comes in. Ford is interested in making batteries that are safer, more energy and power-dense, and easier to recycle. To do that, they have to understand chemical properties of potential new materials like charge and discharge mechanisms, as well as electrochemical and thermal stability.

The team wanted to calculate the ground-state energy (or the normal atomic energy state) of LiCoO2, a material that could be potentially used in lithium ion batteries. They did so using an algorithm called the variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) to simulate the Li2Co2O4 and Co2O4 gas-phase models (basically, the simplest form of chemical reaction possible) which represent the charge and discharge of the battery. VQE uses a hybrid quantum-classical approach with the quantum computer (in this case, 20 qubits in an IBM statevector simulator) just employed to solve the parts of the molecular simulation that benefit most from its unique attributes. Everything else is handled by traditional computers.

As this was a proof-of-concept for quantum computing, the team tested three approaches with VQE: unitary coupled-cluster singles and doubles (UCCSD), unitary coupled-cluster generalized singles and doubles (UCCGSD) and k-unitary pair coupled-cluster generalized singles and doubles (k-UpCCGSD). As well as comparing the quantitative results, they compared quantum resources necessary to perform the calculations accurately with classical wavefunction-based approaches. They found that k-UpCCGSD produced similar results to UCCSD at lower cost, and that the results from the VQE methods agreed with those obtained using classical methods—like coupled-cluster singles and doubles (CCSD) and complete active space configuration interaction (CASCI).

Although not quite there yet, the researchers concluded that quantum-based computational chemistry on the kinds of quantum computers that will be available in the near-term will play “a vital role to find potential materials that can enhance the battery performance and robustness.” While they used a 20-qubit simulator, they suggest a 400-qubit quantum computer (which will soon be available) would be necessary to fully model the Li2Co2O4 and Co2O4 system they considered.

All this is part of Ford’s attempt to become a dominant EV manufacturer. Trucks like its F-150 Lightning push the limits of current battery technology, so further advances—likely aided by quantum chemistry—are going to become increasingly necessary as the world moves away from gas burning cars. And Ford isn’t the only player thinking of using quantum to edge it ahead of the battery chemistry game. IBM is also working with Mercedes and Mitsubishi on using quantum computers to reinvent the EV battery.