Deepfakes can be fun. Those videos that perfectly inserted Jim Carrey into Jack Nicholson’s role in The Shining were endlessly entertaining. As the upcoming U.S. election closes in, however, analysts expect that deepfakes could play a role in the barrage of misinformation making its way out to potential voters.

This week, Microsoft announced new software called Video Authenticator. It’s designed to automatically analyze videos to determine whether or not algorithms have tampered with the footage.

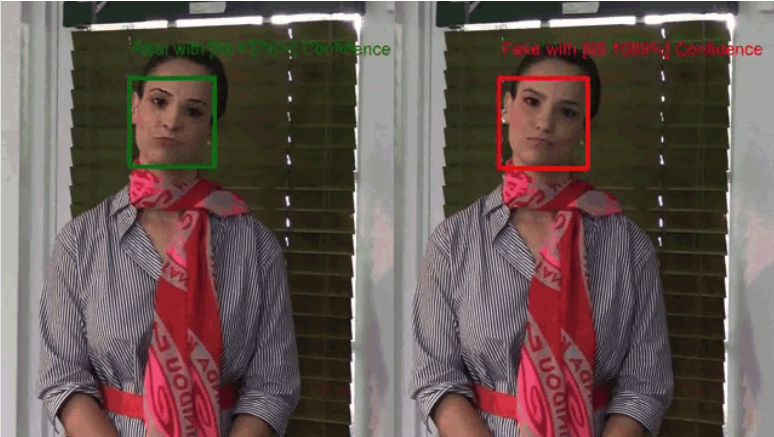

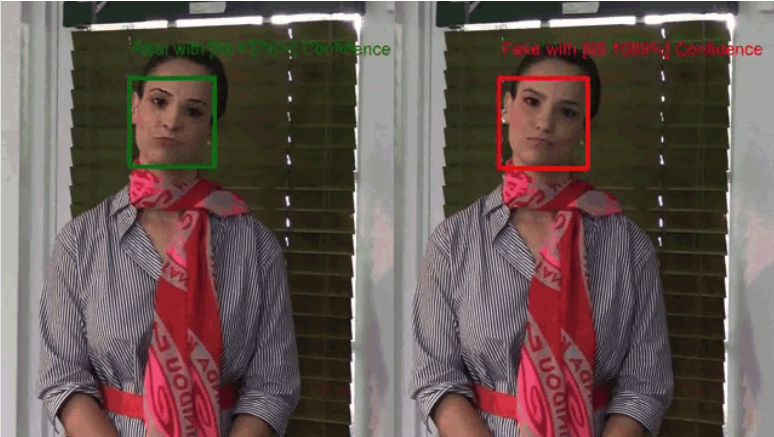

The software analyzes videos in real-time and breaks it down frame-by-frame. In a way, it works similarly to familiar photographic forensic techniques. It looks for inconsistencies in edges, which can manifest as subtle changes in color or small pixel clusters (called artifacts) that lack color information. You would be hard-pressed to notice them with your own eyes, especially when dozens of frames are zipping by every second.

As the software performs its analysis, it spits out either a percentage or a confidence score to indicate how sure it is about an image’s legitimacy. Faking an individual frame is relatively simple at this point using modern AI techniques, but movement introduces an extra level of challenge, and that’s often where the software can glean its clues.

Research has shown that errors typically happen when subjects appear in profile, quickly turn more than 45 degrees, or if another object rapidly travels in front of the person’s face. While these happen relatively commonly in the real world, they rarely happen during candidate speeches or video calls, which are prime targets during an election season.

To train the Video Authenticator, Microsoft relied on the FaceForensics++ dataset—a collection of manipulated media specifically to help train people and machines to recognize deepfakes. It contains 1.5 million images from 1,000 videos. Once built, Microsoft tested the software on the DeepFake Detection Challenge Dataset, which Facebook AI created as part of a contest to build automated detection tools. Facebook paid 3,426 actors to appear in more than 100,000 total video clips manipulated with a variety of techniques, including everything from deep learning methods to simple digital face swaps.

Facebook’s challenge ended earlier this year and the winning entrant correctly identified the deepfakes 82 percent of the time. The company says it’s already using internal tools to sniff out deepfakes, but it hasn’t publicly given any numbers about how many have shown up on the platform.

For now, average users won’t have access to Microsoft’s Video Authenticator. It will be available exclusively to the AI Foundation as part of its Reality Defender 2020 program, which allows candidates, press, campaigns, parties, and social media platforms to provide suspected fake media for authentication. But, down the road, these tools could become more available to the public.

Another big tech company—Google—has been hard at work on ways to detect face swaps; last year it hired actors and built its own dataset using paid actors similar to Facebook’s methods. While Google doesn’t have public plans for a specific deepfake detection site for everyday users, it has already implemented some image manipulation tools as part of its Image Search function, which is often the first step in trying to figure out if a photo is fake.

Microsoft didn’t share specific numbers about the success rate its AI-driven tool achieved, but the benchmark isn’t all that high when you survey the top performing players. The winner of Facebook’s challenge achieved its 82-percent success rate on familiar data—once it was applied to new clips taken in the real world with fewer controlled variables, its accuracy dropped to around 60 percent. Canadian company Dessa had similar success with the Google-produced videos with controlled variables. With videos pulled from other places on the web, however, it struggled to hit the 60 percent success mark.

We still don’t know how big a role deepfakes will play in the 2020 election, and with social media platforms doing their own behind-the-scenes detection, we may never know how bad it could have been. Maybe by the next election, computers will be better at recognizing the handiwork of other automated manipulators.