It can be tough to find archaeological evidence of woven baskets, ropes, and other goods made from plants, particularly in the world’s tropical regions, where warm and humid air breaks down green matter easier than stone or bone fragments. But some microscopic plant bits can stand up to the ravages of time, as shown by rare scraps stuck to three stone tools recently studied in the Philippines. These tiny traces of archaic plant technology are described in a study published June 30 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE, offering indirect evidence of the earliest known tools made for working with the region’s tough vegetation.

[Related: People in China have been harvesting rice for more than 10,000 years.]

A team of researchers found these tools in Tabon Cave, located in the Palawan Province in the western Philippines. The scientists’ radiocarbon dating found these tools were as old as 39,000 years, pushing back the timeline of Southeast Asia’s fiber technology. Previously, the oldest evidence of plant goods in the area were roughly 8,000 year old fragments of mats found in southern China.

Compared to the toolkits found from prehistoric groups in Africa or Europe, stone tools in Southeast Asia were not very standardized, using diverse sizes and shapes. According to study co-author Hermine Xhauflair, a prehistorian and ethnoarchaeologist at the University of the Philippines Diliman, some scientists believe that this difference was due to adaptations to the environment that spurred an “Age of Bamboo.” Similar to the Stone Age or Bronze Age, which heavily relied on their namesake materials, tools at this time were likely mostly made of plentiful bamboo. This organic material doesn’t preserve well, so scientists must look for micro-traces for evidence of this critical chapter in human history.

“Mastering fiber technology was a very important step in human development,” Xhauflair tells PopSci. “It means that people had the potential and the capacity to make objects from multiple parts, bound by fiber; they could build complex houses and structures, make baskets and traps, string bows to hunt, rig sails to boats, and even build the boats.”

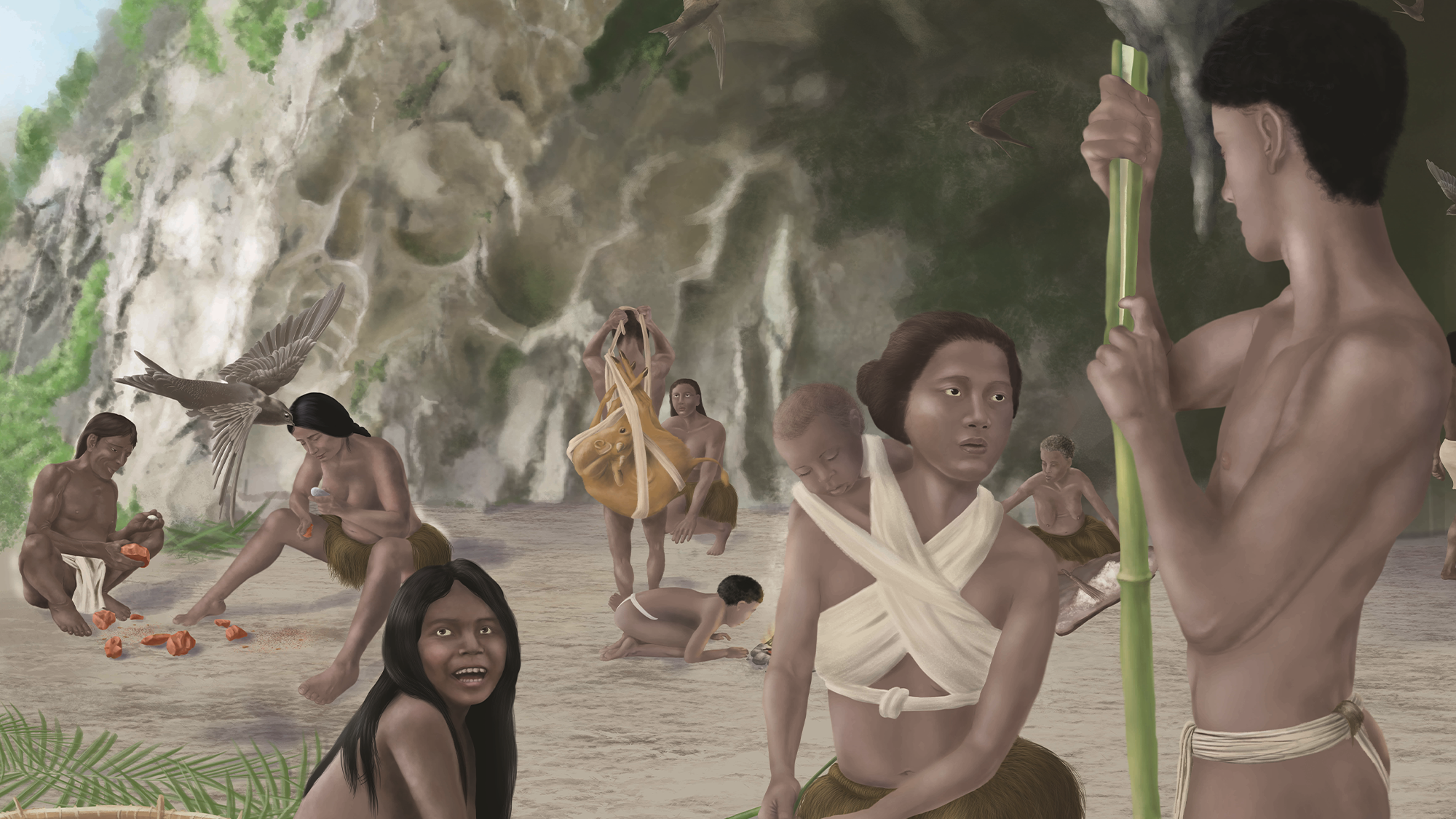

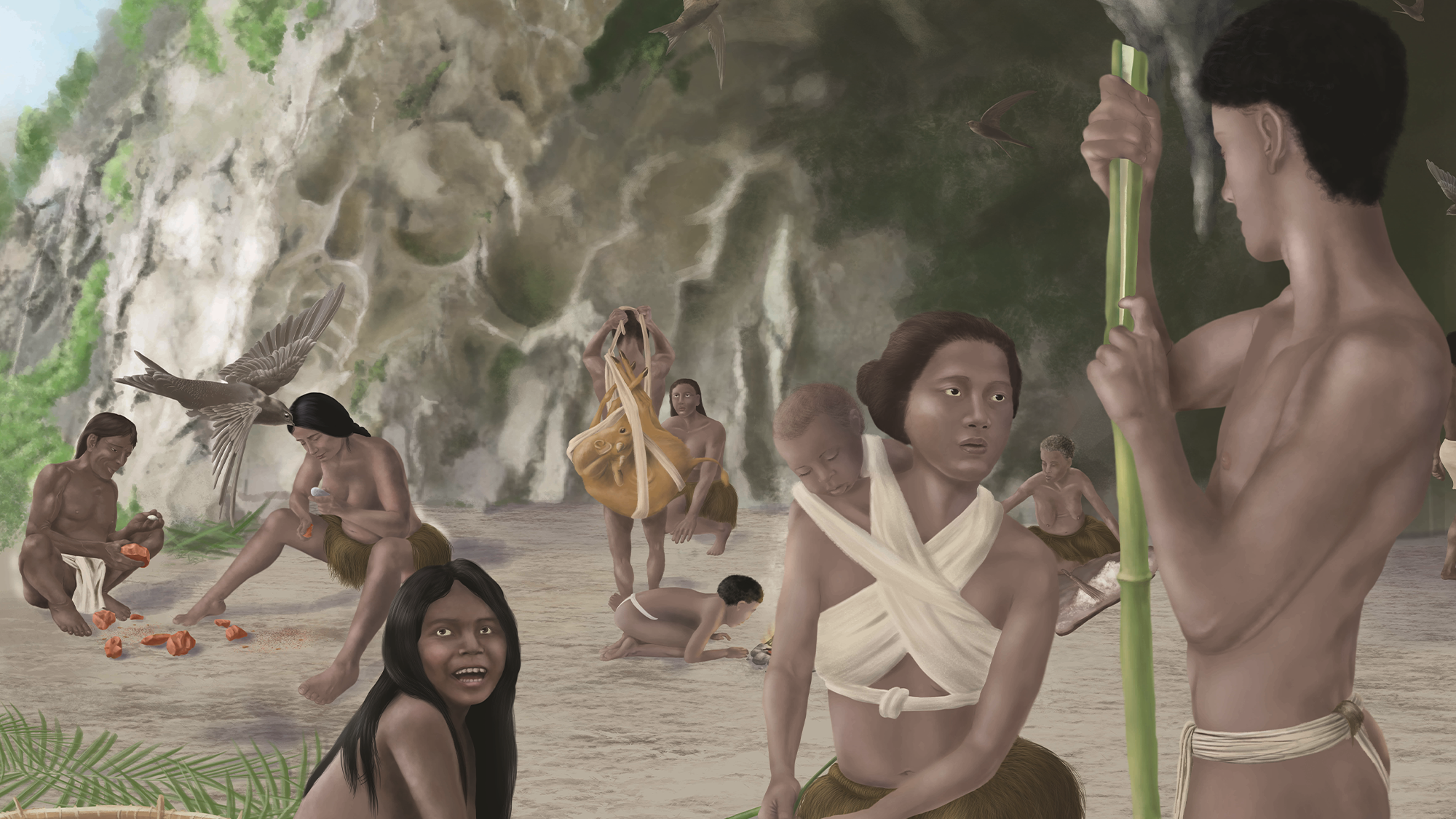

The stone tools that Xhauflair and her team found in Tabon Cave show microscopic evidence of the wear and tear associated with fiber technology. They looked at the plant processing techniques still used by the region’s Indigenous communities, including the Tagbanua, Palaw’an, Tao’t Bato, Molbog, Batak, Agutaynen, and Cuyonon. Rough and rugged plants such as palm and bamboo are stripped and their stems are turned into supple fibers for weaving or tying.

[Related: ‘Fingerprints’ confirm the seafaring stories of adventurous Polynesian navigators.]

Building from these contemporary practices, the team conducted multiple surveys and fieldwork in the rainforest near the cave to find the signature of the different plants and fiber technologies. From that, they could build a database. They then used optical, digital, and scanning electron microscopes on the stone tools from Tabon Cave and found consistent patterns of damage to the stone tools and the ones used today.

Further study will shed light on how the ancient residents of Tabon Cave made baskets, traps, ropes for houses, bows for hunting, and more. This discovery also raises the question of whether plant-based techniques have persisted, uninterrupted, for hundreds of generations. “The technique used nowadays to process plant fibers in the region was already known 39,000 years ago. Are we in [the] presence of a very long-lasting tradition?” Xhauflair asks. “Or was this technique discovered at several points in time and abandoned?”