When you’re sick with some kind of infection, it’s crucial to quickly figure out what’s causing it. But if it’s a viral infection, identifying the exact type of virus is often a laborious and time-consuming process.

A group of researchers at the University of Texas, Austin have come up with a way to detect the presence of a single virus in a person’s urine. The researchers think it could be applied to detect the presence of any virus, from Zika to HIV. Their work was published this week in the journal, PNAS.

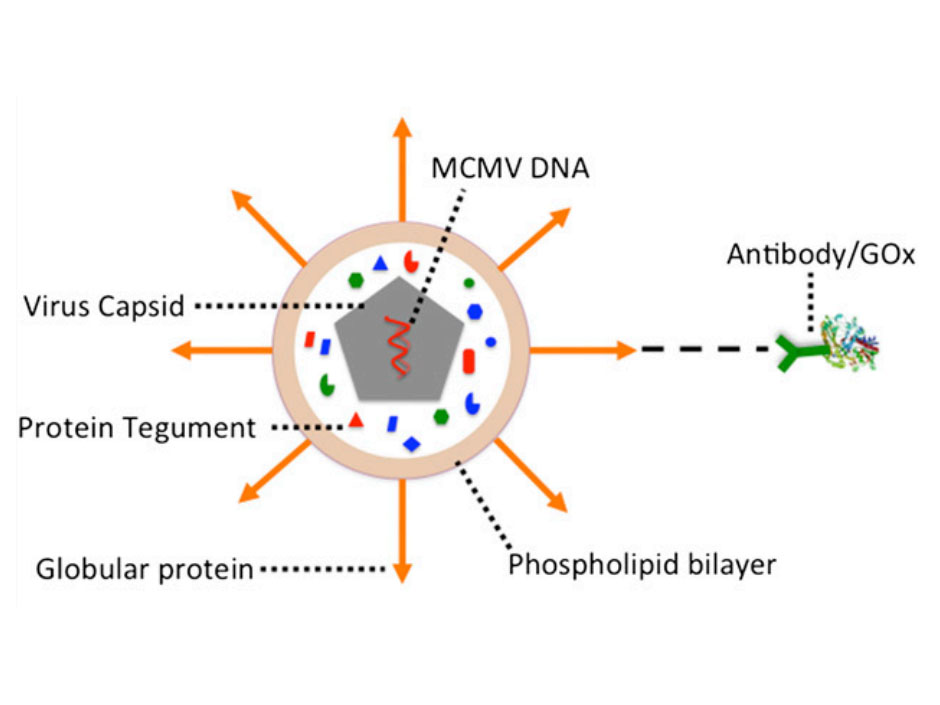

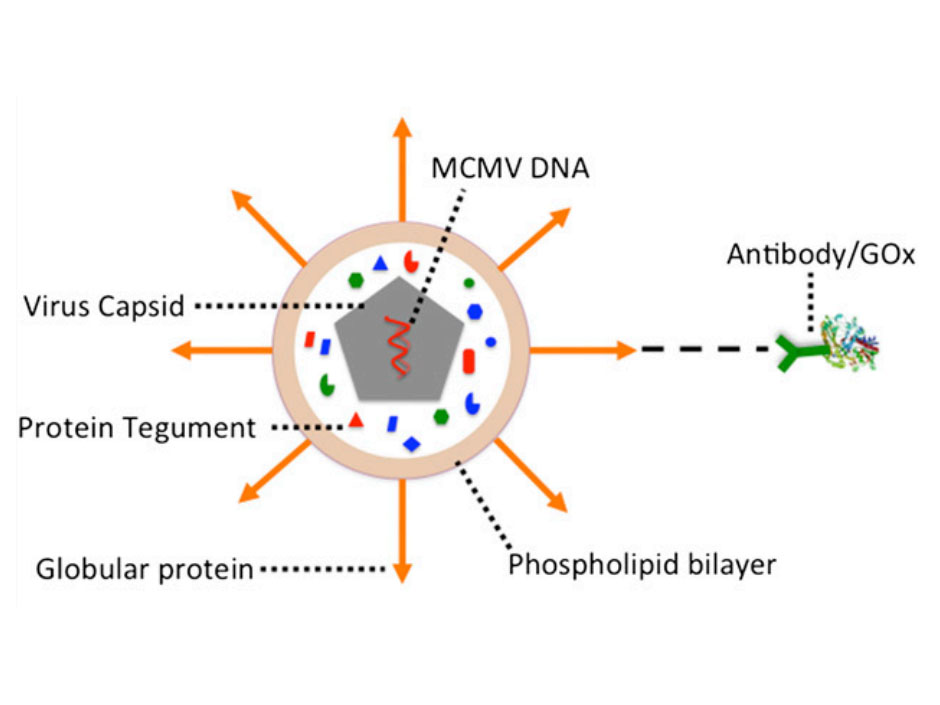

The technique, called a digital electrochemical immunosensor, uses an extremely thin electrode. The electrode, which is thinner than a human cell, is placed in a sample of urine from an infected person. Then researchers add enzymes and antibodies that are naturally attracted to the particular virus that they are trying to detect. If a virus is present, the enzymes and antibodies will stick to it, creating clumps that are big enough for the tool to detect. At least one of those clumps will bump into the electrode and, once it does, the collision will create a boost in electricity, which lets the researchers know that the virus is present.

In their experiment, the researchers focused on a single, large type of virus called the human cytomegalovirus or HCMV, a virus that affects young children and requires early detection. While this is the first virus they have tried it on, the researchers report that the method could also be used to detect other viruses, like HIV, Ebola, and Zika.

This method has many advantages that other viral detectors don’t have, including the speed and precision of the method, the ability to function with a very low concentration of viruses, and, because it is only focusing on one virus at a time, it reduces the chances of a false negative, which happens when other viruses or substances get in the way. There are two other existing methods that detect viruses in urine, however, according to the press release, the researchers say that those need a higher concentration of viruses, or a purification process.

But the researchers say that they still have a long way to go. The electrodes, because they are so sensitive and adhere to so many clumps of compounds, naturally become less stable the more they are used. Most importantly, though, the researchers say, this experiment serves a model to design better, more durable electrodes, that can be applied to any virus type and used in a clinical setting.