Scene: A Royal Air Force station in Great Britain during World War II. Two medics, Tom and Fred are enjoying tea and toast. An officer arrives and orders the medics go out with a stretcher to retrieve a captured German pilot who was wounded when he ejected from his plane over British territory.

Tom: Dash it all, Fred, doesn’t this bloody Nazi pilot look just like the Nazi with the broken femur we just sent back through the POW exchange a few weeks ago? How could he be up and flying again so soon with an injury like that? He should have been bedridden with his leg up in traction for months!

Fred: Crikey, old chap, I do believe you’re right! [Addresses the Nazi pilot] Here now, tell us how you managed to get up and about so soon after cracking your femur?

German Pilot: Nein.

Tom: Come on, old boy, tell, are doctors in Germany so special they’ve got you cured already?

German Pilot: [stubbornly]: Nein!

Fred: Oi, maybe he wasn’t the fellow with the femur fracture anyway—let’s x-ray his leg and see!

Tom and Fred x-ray the stubborn Nazi pilot’s leg.

Tom: [looking at x-ray]: Blimey, that German has got a massive rod!

Fred: [pause] Tom, you mustn’t talk that way . . . [looks at x-ray] By Jove he does have a massive rod—in his thigh! It’s like a giant metal pin holding the bones together. I-I’ve never seen a thing like it!

End scene – exeunt all

Hold it Together

That may not be exactly how we learned about the German invention of intramedullary rods, but so goes the lore among orthopedic surgeons. Intramedullary rods are long metal nails that surgeons use to stabilize and align certain types of fractures. The rod is inserted into the bone marrow, in the center of long bones (like the femur) and shares the load that the bone must support.

Prior to Dr. Gerhard Küntscher’s Nazi-aiding invention, the most common treatment for many long bone fractures involved the use of traction—immobilizing patients in bed for weeks, with limbs suspended in midair by a series of pulleys and counterweights.

Patients with intramedullary rods, on the other hand, often can use their injured extremity much more quickly. Thanks to Küntscher, German soldiers wounded during World War II could be remobilized far faster than their Allied counterparts. And if the edge didn’t pan out, the discover changed the face of fracture treatment; to this day, people refer to intramedullary rods as “Küntscher rods.”

Tighten Up

Back in the 1950s, if you were unlucky enough to be born with uneven limbs, you were pretty much stuck, destined to a life of hobbling around and an unfortunate childhood nickname like “Gimpy Joe.” Maybe you could try to hide the defect by wearing a shoe with an extra-thick sole, hoping (futilely) that the snot-nosed kids on the playground wouldn’t tease you too much. The situation was equally grim if a bad injury or infection left you with legs of different lengths. That is, until a creative Soviet physician in rural Siberia named Dr. Gavril Ilizarov invented the external fixation device that bears his name: the Ilizarov apparatus.

Using old bicycle parts (so the legend goes) Ilizarov constructed a multi-ring circular frame. He deliberately fractured a patient’s bone and inserted the apparatus; as the patient’s bone began to heal and grow back together, Ilizarov would adjust and tighten the frame, stretching the healing bone out millimeter by millimeter. (Yes, this process is uncomfortable . . . and now the playground punks will probably call you “freaky Robo Joe” because you have giant metal rings and spikes protruding from your leg. Sometimes you just can’t win. ) Over time, a limb with an Ilizarov device can be lengthened significantly; when the procedure is finished, the apparatus is removed and voilá, the patient has a longer leg. (And, finally the chance to kick some major butt.) An Ilizarov device can also be used in certain types of messy and complicated fractures where other techniques (like the above mentioned intramedullary rod) are not feasible. To this day, the Ilizarov device is one of the most common methods employed in limb-lengthening procedures—although these days the apparatus is made of materials somewhat more sophisticated than Gavril’s old bicycle.

Give it a Grab

These rods and apparatuses, however, have nothing Krukenberg’s operation. This form of prosthetic is by far my favorite procedure (I even choreographed an interpretative dance to celebrate the fine doctor Kruckenberg, but somehow, my act got cut from my med school talent show). While there are plenty of snazzy prosthetic hands available, prosthetics are not always a possibility in certain situations. For instance, in third world countries, maintenance and repair of expensive prosthetic devices can be difficult; children in such countries may not be able to obtain appropriately sized prosthetics when they outgrow their old ones. Likewise, many hand prostheses require adequate vision for functionality; you need to be able to see the object you are trying to grab with your artificial claw hand in order to properly manipulate your prosthetic device. Blind patients who have lost their hands consequently have limited options for prostheses. Enter the operation invented by Dr. Hermann Krukenberg, a German physician born in the 19th century.

First, let’s have a quick anatomy review. There are two long bones in the forearm, the radius and ulna, which run from your elbow to your wrist. The radius can rotate around the ulna. (Bend your elbow and turn your palm to face the floor, and then the ceiling—if you had x-ray vision, you could see your bones rotating around one another.) Krukenberg developed a method for taking the radius and ulna of a handless patient and transforming these two bones into a giant pincer claw—like having a set of giant fleshy chopsticks attached to your elbow. When patients were healed, they could use their pincer to grasp objects with fairly good control; since the claw was an integral part of their own body, they still had sensation and could feel and manipulate objects—even with their eyes closed. The end result might look bizarre, even creepy—but many patients love the new independence they gain from a functional Krukenberg arm.

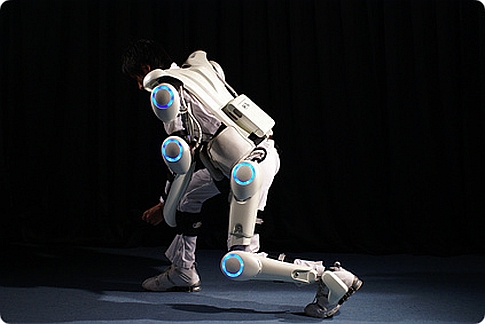

These days, you can read many articles about cutting-edge, high-performance prosthetics. Just recently, Oscar Pistorius, a bilateral below knee amputee from South Africa was almost banned from the Olympic trials because officials feared his artificial legs gave him too great of an advantage over able-bodied runners. Other prosthetic devices are geared those who are more aesthetically, and less athletically, inclined; one designer is working on anEames-inspired prosthetic leg, modeled after the famously graceful and stylish Eames chairs of the mid-twentieth century. Likewise, surgeons today in the twenty-first century are blessed with incredible technological resources, everything from the tiny fiber optic cameras of laparoscopy, to space-age super-strong, super-light metal hardware. Amidst this wealth of functional and visual appeal, it can be easy to forget about older, simpler, but still vital and elegant devices and surgical methods such as those of Drs Küntscher, Ilizarov and Krukenberg—three physicians who used a little ingenuity, some household odds and ends, and the bones of the human body itself, to develop techniques that gave surgery a major leg up and helping hand.

See Küntscher, Ilizarov and Krukenberg techniques (as well as some of their high-tech alternatives) in action; launch the gallery here.