Hummingbirds are some of the world’s fastest birds and must frequently squeeze through tiny spaces in plants to get to the nectar that they need to keep up their energy. However, over time, they have lost their ability to fold their wings close to their bodies at the wrist and elbow like other birds. How hummingbirds squeeze into such tight spaces has remained a mystery to ornithologists until now. A study published November 9 in the Journal of Experimental Biology found that they deploy two very specific strategies: the sideways and the bullet.

[Related: This hybrid hummingbird’s colorful feathers are a genetic puzzle.]

Into the flight arena

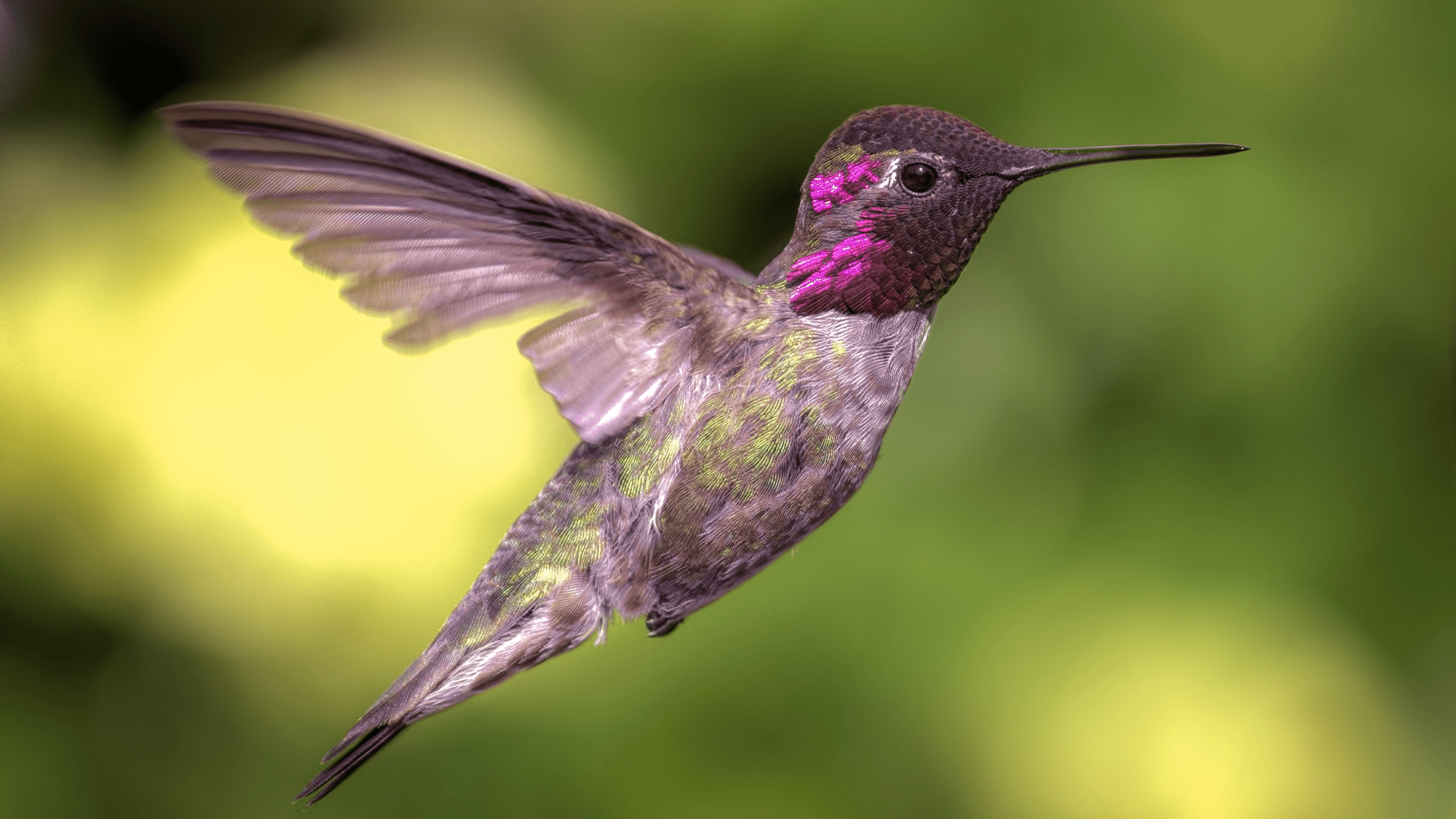

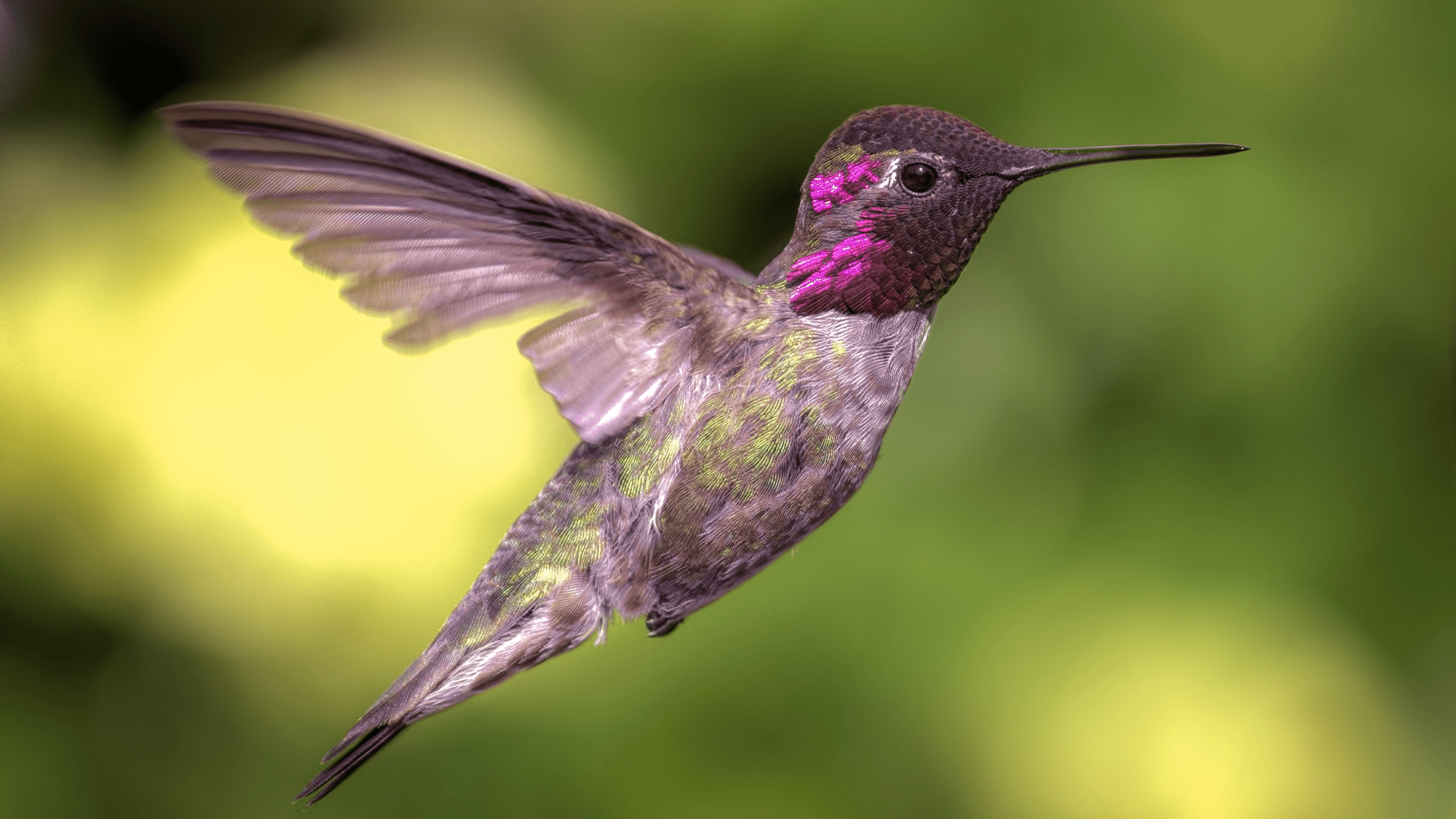

The study focused on Anna’s hummingbirds (Calypte anna). These are among the most common hummingbirds living along the West Coast of the United States. They are about the size of a ping-pong ball and have iridescent emerald feathers and sparkling pink throat plumage.

A team from the University of California, Berkeley designed a two-sided flight arena for the experiment. They used alternating rewards to train the hummingbird to fly through a 2.48 square inch gap in the partition that separated the two sides of the arena. To do so, they only refilled a feeder shaped like a flower with a sip of sugar water if the bird returned to the feeder that was on the other side through one of the gaps. This encouraged the birds with an only 4.7 inch-wide wingspan to flit around the arena.

The team then replaced the gap between the two sides of the flight arena with a series of smaller oval and circular openings that ranged from 4.7 inches to only 2.3 inches in height, width, and diameter. The birds’ movements were recorded using high-speed cameras, to get a sense of how they negotiated the various openings.

Next, the team wrote a computer program to methodically track the position of each bird’s bill as it approached and passed through each hole. The program also pinpointed where the hummingbird’s wing tips were, to calculate their wing positions as they transited through.

[Related: These female hummingbirds don flashy male feathers to avoid unwanted harassment.]

The experiment revealed that the hummingbirds used two unique strategies to negotiate the gaps.

The sideways

In the first strategy, the hummingbirds approached the circular opening and usually hovered in front of it to assess its size. They then traveled through it sideways, reaching forward with one wing and sweeping the second wing back, similar to the shape of a cross. Their wings were still fluttering to fly through the door and then swiveled forward to continue on their way.

The bullet

For the second strategy, the birds swept their wings backwards, pinning them to their bodies. They then quickly shot through the opening beak first like a bullet, before sweeping their wings forward. They resumed flapping their wings once they were safely through the circle. All of the hummingbirds in the study generally deployed this technique as they grew bolder and more familiar with the arena.

Changing tactics

The team observed that the hummingbirds who used the first strategy of sideways traveling tended to fly more cautiously than those that shot through the circles beak first. As the birds became more familiar with the openings after multiple approaches, they appeared to become more confident. They started to approach them quicker and dropped the more sideways way of getting through in favor of shooting through beak first.

For the smallest opening–only half a wingspan wide–every bird zipped through facing forward with their wings back. Even the more cautious birds did this on their first attempt to avoid collisions.

According to the team, about eight percent of the birds in the experiment clipped their wings as they passed through the partition and only one experienced a major collision. The bird who did experience the collision was able to successfully reattempting the move and continue flying.