Carl Sagan dreamt of navigating the cosmos on sails pushed by waves of photons streaming out from the sun. These solar sails may one day carry humans to other planets and maybe even other star systems. The Planetary Society, led by CEO Bill Nye “The Science Guy”, aims to make this dream a reality.

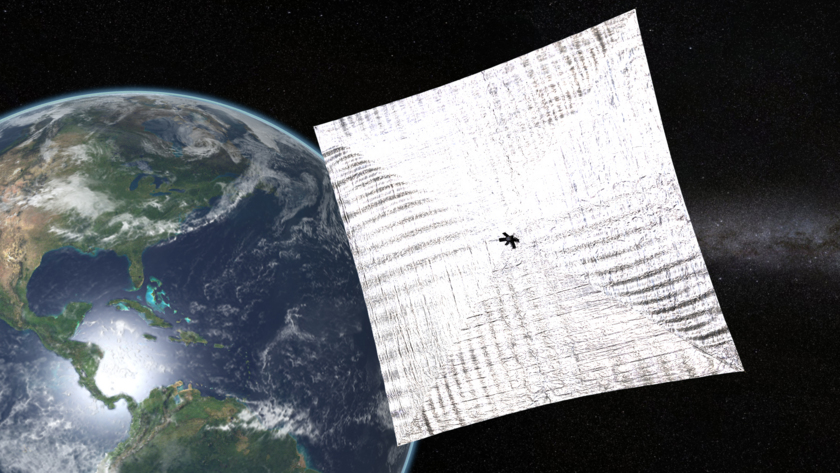

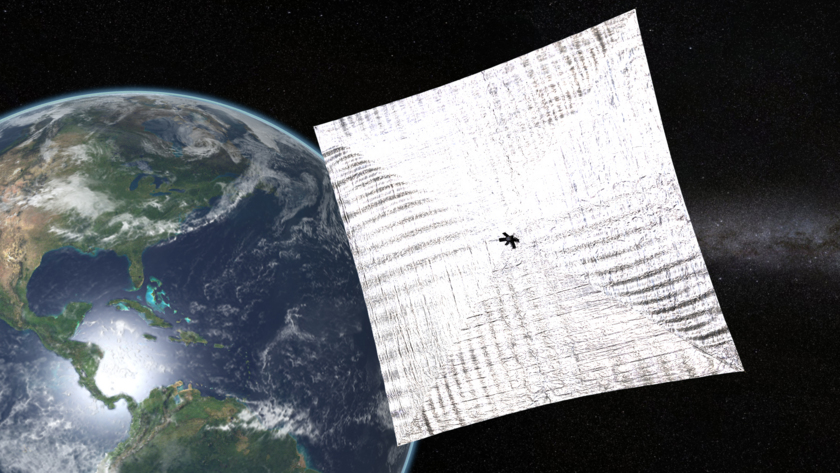

Last year, the society’s solar sailing spacecraft, LightSail, proved it could deploy a set of silvery Mylar sails in the vacuum of space. Next year, LightSail 2 will prove to the world that those sails can harness the power of the Sun to propel the spacecraft.

The shoebox-sized satellite is slated to launch on one of the first flights of SpaceX’s highly anticipated Falcon Heavy rocket in 2017, and will conduct the first controlled solar sail flight in Earth orbit. But before that can happen, the craft had to undergo a rigorous test in May to demonstrate it’s ready to fly.

The first LightSail successfully deployed its sail in space but ran into some problems. The tiny satellite overcame a myriad of issues including software glitches, signal losses, and even battery issues, before beaming back the ultimate selfie. Things are already looking up for its successor.

In the recent flight simulation, LightSail 2 proved it can successfully deploy its antenna and solar panels, communicate with ground stations, and unfurl its 344-square-foot solar sails with only a few minor glitches.

Go Booms, Go

The test took place at the California Polytechnic State University, approximately three hours north of Los Angeles, nestled in the heart of California’s central coast. Cal Poly’s aerospace engineers developed much of the technology that will fly with LightSail 2.

When I arrived at Cal Poly at around 9 in the morning, there was already a small crowd of students lined up outside the engineering building, hoping to get a glimpse of Bill Nye and the tiny satellite. Dave Spencer, LightSail’s project manager, gave reporters a rundown of everything we could expect from the test.

“Basically, today is the full mission compressed into one day,” he said. “This is the most complex test we’ll do during development.”

The first part of the test would take place in a small clean room, said Spencer. Here the satellite would act as if it had just been deployed in space, proving it can power up before deploying a set of solar panels and its communications antenna. After a lunch break and recharging session, the satellite would put on the real show: deploying those shiny solar sails.

The morning’s mission critical steps went off as planned and the satellite showed it was ready for the main event. It was standing room only in the high bay as crowds gathered inside as well as outside the glass to catch a glimpse of the solar sail in action.

LightSail 2 rolled across a small courtyard as if walking down the red carpet. Once in the high bay, engineers worked to secure it in the center of a large low-friction deployment table. Here LightSail would deploy four 13-foot booms, which would pull 344-square-feet of silvery Mylar material into a taut square.

Engineers manned their computers, anxiously awaiting the data that would soon be pouring in and Bill Nye pumped up the crowd before uttering the words we were all waiting to hear: “We are GO for sail deployment.”

Following a launch-style countdown, the crowd cheered “Go booms, go” as the satellite’s motor whirred to life, releasing the sails. From start to finish, the deployment took approximately three minutes. Each boom is marked with five notches and the Planetary Society logo (in white epoxy ink), so when visible these notches indicate that the booms are fully deployed. The team chose to make the indicators white so engineers can easily spot them with the onboard cameras.

LightSail 2 responded instantly to commands, resulting in what looked like a picture-perfect deployment. However, the team soon realized that the boom extensions fell a few centimeters short of the target, and the deployment motor was still running. The satellite then failed to respond to commands to shut down the motor, so the team had to manually power it down.

Following the test, we spoke to Bill Nye and Jason Davis, the Planetary Society’s resident LightSail experts, to find out what went wrong.

The booms stopped short of their target, Davis explained. “It turns out the motor couldn’t push any further because there was too much tension on the booms from a combination of boom flexing, and friction from the deployment table,” he said. Interference from the communications antenna is what prevented the motor from turning off.

According to Davis, the flexing or friction won’t be an issue in space, but the spacecraft could damage itself if the motor continues to run. “The engineers are adding a timer that automatically shuts off the motor after a few minutes regardless of whether the booms are deployed or not,” Davis explained. “We can always walk the booms out incrementally at a later time.”

“There are always things to tweak following a test like this, and there are many more details to work out,” Nye added. “Overall this test went as planned and ran much more smoothly than last year’s.”

Nye then explained how excited he was to see the satellite transmitting data. “I was a Boy Scout,” he explained. “So one of the most exciting things about LightSail [for me] is that it transmits Morse code.” Every few seconds the satellite transmits a beacon signal which includes data on the spacecraft’s health and status. Included in these packets is a special message. The spacecraft will talk to anyone who is tuned in to the megahertz frequency 437.325, as it transmits “LS2” (for LightSail 2) in Morse code every 45 seconds.

Onward And Upward

The next stop for LightSail will be Utah State University’s Space Dynamics Laboratory for attitude control system testing. The craft will then be integrated with Prox-1 (another small satellite) before moving onto the launch site for vehicle integration.

Following the launch, LightSail 2 will gradually raise its apoapsis (highest point in orbit) for about a month, demonstrating that the sunlight produces a measureable effect on its orbit. To do this, the satellite will deploy its sails and then tack back and forth just like a sailboat navigating the seas.

NASA is highly interested in the data that the Planetary Society is generating. In 2018, the space agency will launch the NEA Scout mission, which will use solar sails to fly to a nearby asteroid. Humans won’t be flying on solar sails anytime soon, but each mission brings the dream of sailing on sunlight one step closer to reality.