The Namibian savanna is dotted with 13-foot-tall towers of sandy soil. Built by termites just a fifth of an inch long, these mounds aren’t only structural feats—they’re a biological extension of the 1.5-million-bug colony inside. Though researchers are still trying to figure out how the “brain” of the swarm works (how do termites plan a mound without any blueprints?), they’ve recently uncovered a lot about the entomological monuments. “The functioning organism is really the whole colony,” explains Hunter King, a physicist at the University of Akron who studies the mechanics of insect swarms. “The mound really is the lung and the respiratory exchanger—and a protective skin for the superorganism.” Here’s how these skyscrapers work.

1. Hand to mouth

Covered walkways up to 4 inches wide and 230 feet long lead out to the grass, vegetation, and dung that termites munch. There, tiny workers build fractal-like networks of smaller, branching corridors, and gobble up fresh supplies—but no digestion will happen until they’re back at the nest.

2. Skin

Termites pack the mud so it’s porous enough to allow fresh air to slowly seep in, but solid enough to keep out intruders such as predatory ants. If breached by a wayward elephant or a probing human, workers immediately swarm up from the nest below to protect and repair the structure.

3. Microbiome

This subfamily of termite outsources gut microbes, growing a fungus that acts as a digestive tract. Workers mold their harvest onto the fungal masses, which break down plant gunk into edible sugars and nitrogen. This creates CO2, which would suffocate the bugs if their mound didn’t circulate it out.

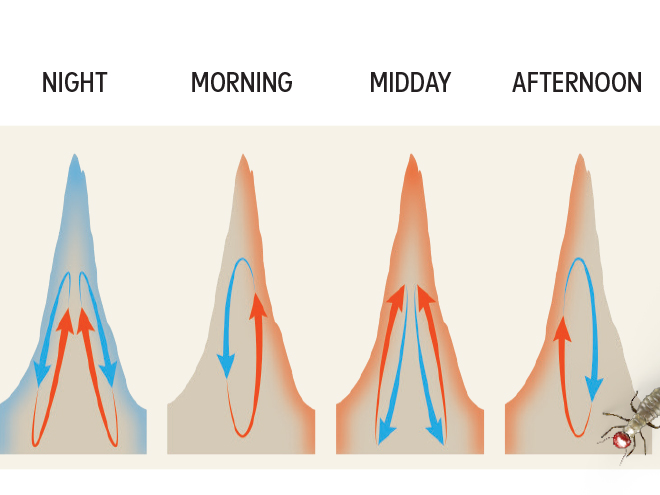

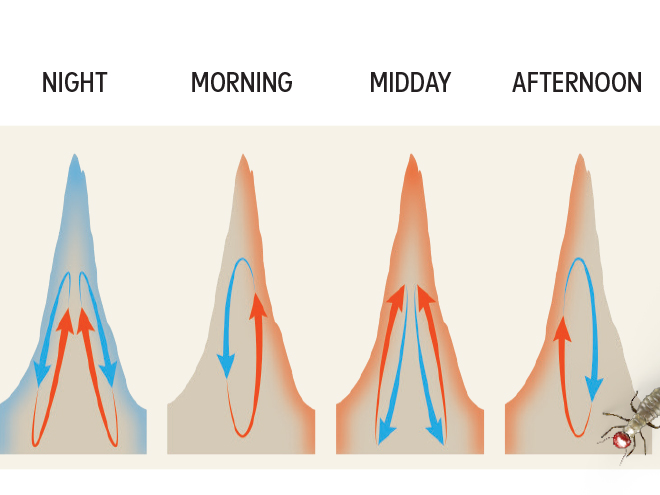

4. Lungs

A mound breathes like we do—but instead of a diaphragm, temperature drives oxygen flow. The sun heats ducts near the exterior, creating a density shift that brings up a stale breeze from inside the nest. Fresh air enters through porous mud and sinks in the cool interior. This reverses in the chill of night.

5. Reproductive system

Almost everything happens below ground. Workers constantly bring food to the queen’s central chamber and shuttle eggs to nearby nurseries. Temps inside fluctuate by about 30 degrees through the year, but humidity levels—important for the colony’s fungus—stay at around 80 percent.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2018 Tiny issue of Popular Science.