In Overmatched, we take a close look at the science and technology at the heart of the defense industry—the world of soldiers and spies.

ON THE WEBSITE Soar.Earth, you’ll find a map of the world that at first looks a lot like the one on Google Earth. But zoom in, and rectangles appear. Click on one, and you might find an image from a 1960s spy satellite showing a fresh crater from a nuclear-weapons test. Scoot to different coordinates, and see high-resolution satellite shots of last year’s floods in Western Australia. Northwest of that, there’s a map showing where Saudi Arabia has excavated for a futuristic, 110-mile-long city called The Line.

The site’s founder, Amir Farhand, has big dreams for Soar: He hopes it will become the world’s biggest atlas, allowing users to see all the information that people have gathered about any point on Earth.

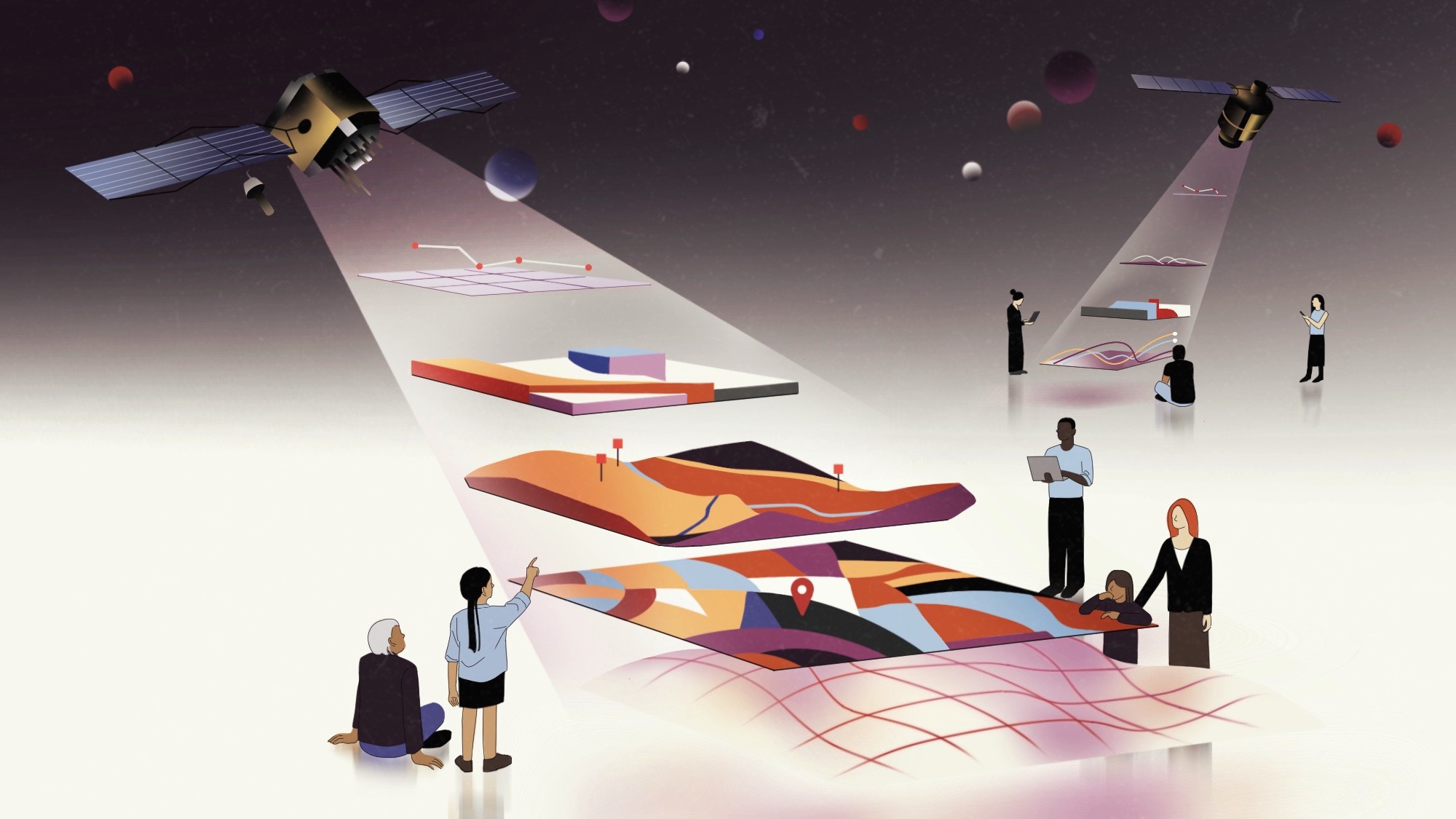

While achieving that dream is perhaps impossible, or at least a long way away, Soar already hosts oodles of historical maps, satellite shots from sources like NASA, and even cartography from scientific papers. Containing past and present maps while allowing users to also commission images from satellites, Soar can track the intersecting interests of many different groups: climate scientists, developers, intelligence analysts, mining experts, and defense contractors.

The interests of the last two groups are, in fact, what spurred Soar’s creation.

Charted territory

Farhand, who lives in Australia, was always a plot-the-world kind of guy. He moved a lot as a kid, but wherever he was, he would ride his bike around his neighborhood and make maps of the surroundings.

After learning about satellite imagery and its relevance to Earth science in college, and then dropping out of a PhD program, Farhand became a consultant. He worked all over the world on geospatial projects.

“Then I thought, You know what, I love atlases,” he says. “And I thought to myself, Why aren’t all the world’s atlases in one place?”

Why wasn’t there a spot where he could overlay a leopard habitat range over a climatic map and so see the correlation? Why couldn’t he also see how someone had baroquely hand-drawn the area’s layout hundreds of years ago? Who wouldn’t want that?

Back then, around 2011, those were relatively idle questions for him. But in the years to come, Farhand would take them to work. In 2013, he created an application called Mappt—it contained the early seeds of what Soar would become. A few years after Mappt became available, a new customer took an interest: the US government. In 2017, a defense-centric version called Mappt Military appeared on the National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency’s official app store. Verified Department of Defense or intelligence community members could use it for free. It’s still available today, allowing users to map hazards, plan logistics and transport, and plot place-based risks, among other things.

Defense users and also people in the mining industry were interested in using the technology to build their own private atlases, storing all their geospatial data in one spot, accessible from anywhere. The contents of those atlases ranged from modern drone and satellite photos to pictures taken from airplanes in the 1960s, and they wanted it in the field, offline.

“It was all based on that premise of flexibility of having mapping data on your hands,” Farhand says.

Soar rose, in a way, out of Mappt’s iterations. On the site, users can create their own private atlases—as the defense and mining companies wanted to—and include proprietary data, like satellite images they buy through the site. Or they can upload content for everyone to see, as long as they own its copyright or do their best to attribute public domain and out-of-copyright images. Or they can do both. Interacting with the site is free, as is creating an account, although some features (like making a private atlas) do cost money. Today, both Mappt and Soar.Earth are part of the parent company, Soar.

On the Soar site, users can whip across the screen to anywhere on the planet and see if someone has uploaded an aerial photo from the 1950s, maps of flooding, maps of drought, and plots of elevation—all of which are available for, say, the city of Porto Alegre, Brazil. They can make measurements, add annotations, make different layers transparent and see how they overlap.

The team is currently working through how best to moderate content on the platform to ensure it fits with Soar’s guidelines. Right now, anyone can upload maps in near real time if they agree their data fits with copyright and community guidelines. The Soar team generally logs in and checks on new uploads several times a day. Users can also report violations. Soon, though, the company will split users into two tiers: one of trusted power users who can automatically upload, and another that will have to await Soar’s approval before their maps appear. Farhand compares their policy to what you might find with Google Reviews or YouTube, noting that he’s “hopeful we can use precursor crowdsourcing platforms for directions on what to not to do, as much as what to do.”

If Soar doesn’t yet have the maps a user is looking for, they can request free NASA or Sentinel (a European satellite program) data of the area, buy brand-new shots from commercial satellites, or order archival images—all of which can be done through Soar and added to the public atlas of atlases. “They were very, very early into making it possible to just log into a website and buy satellite imagery,” says Joe Morrison, a vice president at Umbra, a company that takes radar-based data from space.

Morrison writes a popular industry newsletter called “A Closer Look,” about “maps, satellites, and the businesses that create them,” and his analysis often laments the typical difficulty of buying shots from space: The pricing is opaque, the licensing is often restrictive, and actually opening the shutter can take so long the picture is no longer relevant. Soar aims to solve a lot of those problems.

The combination and chronology of the data is interesting to people doing, say, climate research, tracking a conflict, or trying to suss out secret goings-on by using public data. Soar provides a platform on which users can do a form of what’s known as open-source intelligence, or OSINT, which can be a powerful way to track intra- or inter-country dynamics.

Morrison says what sets Soar apart from other geospatial endeavors is that it has focused on creating a community that publicly shares interactive maps. Most people aren’t going to pay for their own shiny satellite pictures, or spend all their free time aligning old National Geographic maps to the Soar lat-long grid, or adding daily updates on the big construction project across town. But some people will.

Farhand thinks of the dynamic like that of YouTube: Many more people watch videos than create them. “We get this beautiful, enriching content from incredible specialists around the world,” he says of Soar’s homegrown influencers. “And then you’ve got these hordes of viewers that come on board.”

Spatial storytelling

One big-audience user who shares regular info on Soar goes by the handle War Mapper. They regularly post maps that consolidate updates on the conflict in Ukraine, showing the extent of territory controlled by Ukraine, or Russian-occupied territory, among other data.

Another popular presence is Harry Stranger, a 23-year-old from Brisbane. “I would consider him an open-source analyst,” Morrison says. “He’s not really a journalist. He’s not really a military analyst. And he’s not just the normal amateur sleuth. He’s somewhere between.”

A while ago, Stranger, a space nerd, wanted to see a picture of a particular launchpad. Like so many interesting things, space infrastructure is hard to reach. You can’t just stroll up to a rocket’s spot on Cape Canaveral. And you definitely cannot do so at China’s Xichang Satellite Launch Center. “People can’t just walk up to and take a picture of it,” he says of such secure spots. But space offers a view of it all. And there aren’t really restrictions—despite rumors to the contrary—on what civilians can nab shots of.

At some point, Stranger heard that he could get satellite images of the launchpad, for free, from Sentinel. “I became addicted,” he says.

Stranger started to keep an eye on various aerospace places in the world, particularly those located in countries that don’t give much public notice of their activities, like China. Was there construction? Is there a rocket rocking on the pad? Sometimes he hears a rumor and starts monitoring the site via satellite. Without having any insider knowledge, he could know more than he ever had before. “Space from space,” he calls his endeavors now.

When you can’t go through, don’t go around: Go above and look down. It is, after all, what the intelligence apparatus has been doing since the satellites that took the photos were invented.

Stranger’s interest in monitoring earthly activity from above mirrors the more automated interests of intelligence programs, like the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity’s SMART program, which aims to create software that can spot terrestrial changes, like heavy construction or new crop growth, from satellite imagery.

Soon, Stranger was interested in what the intelligence types of the past had seen, which he was able to access through the lenses of old spy satellite systems whose images had since been cleared for public release. “I knew it existed out there,” he says of the declassified images. He didn’t think “out there” would end up being as easy as logging into the United States Geological Survey website, but it was.

If the formerly hushed images had already been scanned, he could download them for free, and he soon set up a GoFundMe to pay for the digitization of more. Soar, which Stranger hadn’t really used yet, donated $750.

“That’s where we kind of kicked off our relationship,” he says.

He started uploading the declassified imagery to Soar. Now, anyone can see US spy satellite shots of the Jiuquan Launch Center in China from the 1970s, along with a 2022 commercial-satellite image of a rocket test stand at the site, which was hit by an explosion the year before.

Guide to the planet

Right now, Soar hosts just under 100,000 different maps (excluding the shots from satellites like Sentinel, which add data all the time). Farhand estimates that this six-digit number is less than 0.0001 percent of the world’s total extant maps. “I don’t think that’s good enough,” he says.

But if the company can get up to 1 or 2 percent of the total, he thinks, Soar could become as ubiquitous as Google Maps but with more context and community. That’s the dream anyway—a castle in the air that he’d like to tether to Earth.

Read more PopSci+ stories.