It seems hard to imagine life without today’s ubiquitous navigation apps, even for those of us who remember MapQuest (and printed atlases before that). GPS and directions on-demand are just part of your smartphone’s core functionality—and woe betide any brand that messes this up. Just ask Apple.

Apple, Google, and Microsoft all call their maps app just that: Maps. But they should really be called Directions, because that’s their main usage. Need to know where something is, and how long it will take to get there? The big three have you covered. And so do a bunch of other apps too. Even the search features in these apps are focused on finding a specific location and getting directions to it. But what about everything else you need a map for?

Perhaps you’re in a boundary dispute with a neighbor or your local government. Maybe you want to know exactly how much of a nearby forest has been cleared this year. Or you want something as prosaic as a series of aerial images of your lawn so you can show off how much you’ve improved it over the last few months. These services, and many others, require mapping tools that do a lot more than tell you where to go.

Let’s take a look at a three of these more hardcore mapping services, from the US Geological Survey’s LandSat, a commercial outfit called Planet Labs, and Google too. You might be surprised at what they offer, and what you didn’t even realize you needed from a map.

LandsatLook 2.0

The US Geological Survey (USGS) operates the Landsat satellites with NASA—they’re currently up to Landsat 9, which was launched on September 27, 2021. The USGS’s Earth Resources Observation and Science Center handles Landsat data and makes it available to the public in the form of tens of millions of satellite images. You can explore these images using the LandsatLook 2.0 web viewer.

That “2.0” isn’t just for show. This viewer is a significant upgrade over the earlier version, which didn’t have a familiar zoomable global view. Instead, imagery was portioned into “scenes”—square chunks 115 miles to a side—and displayed one at a time. It wasn’t exactly intuitive.

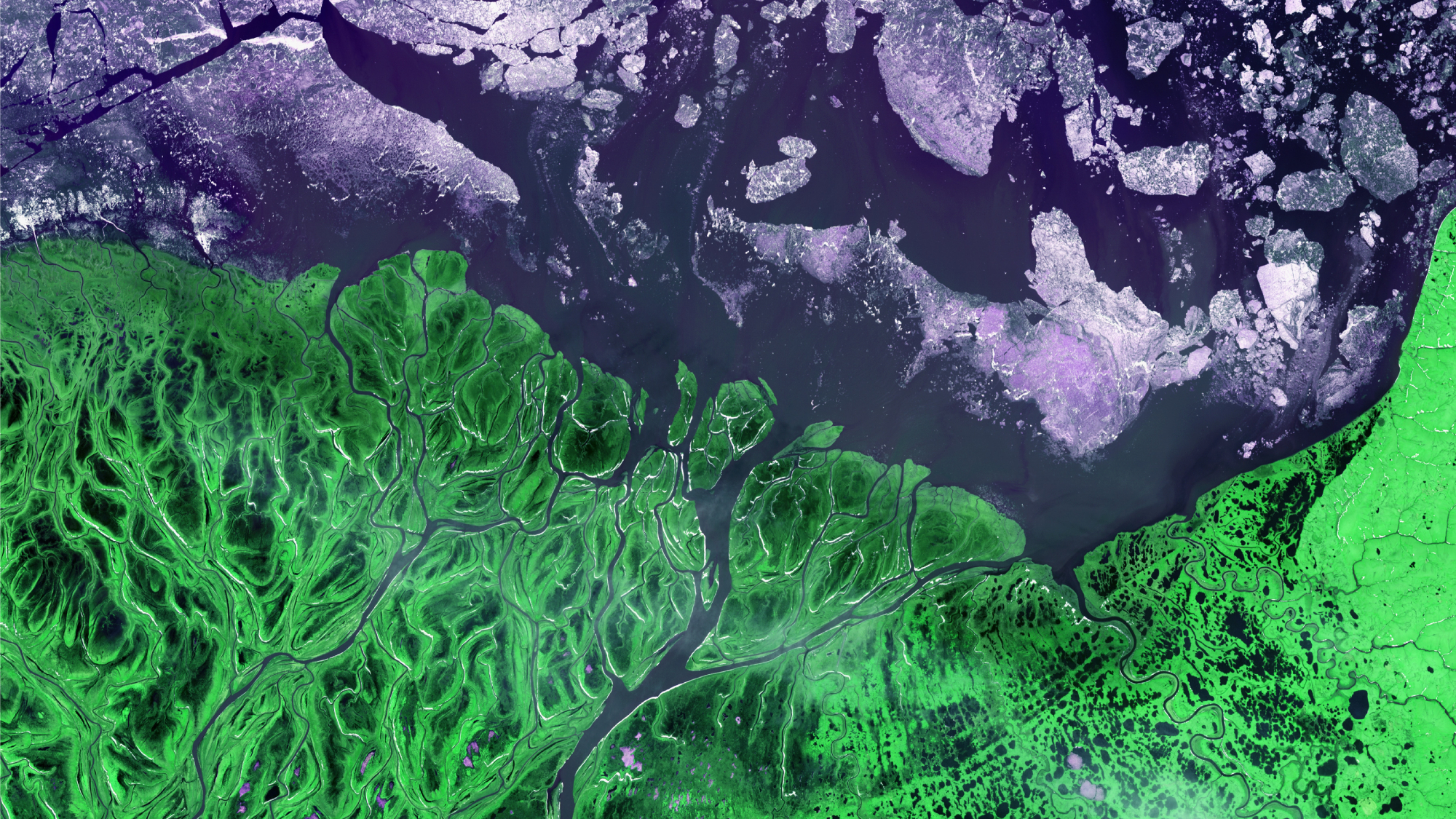

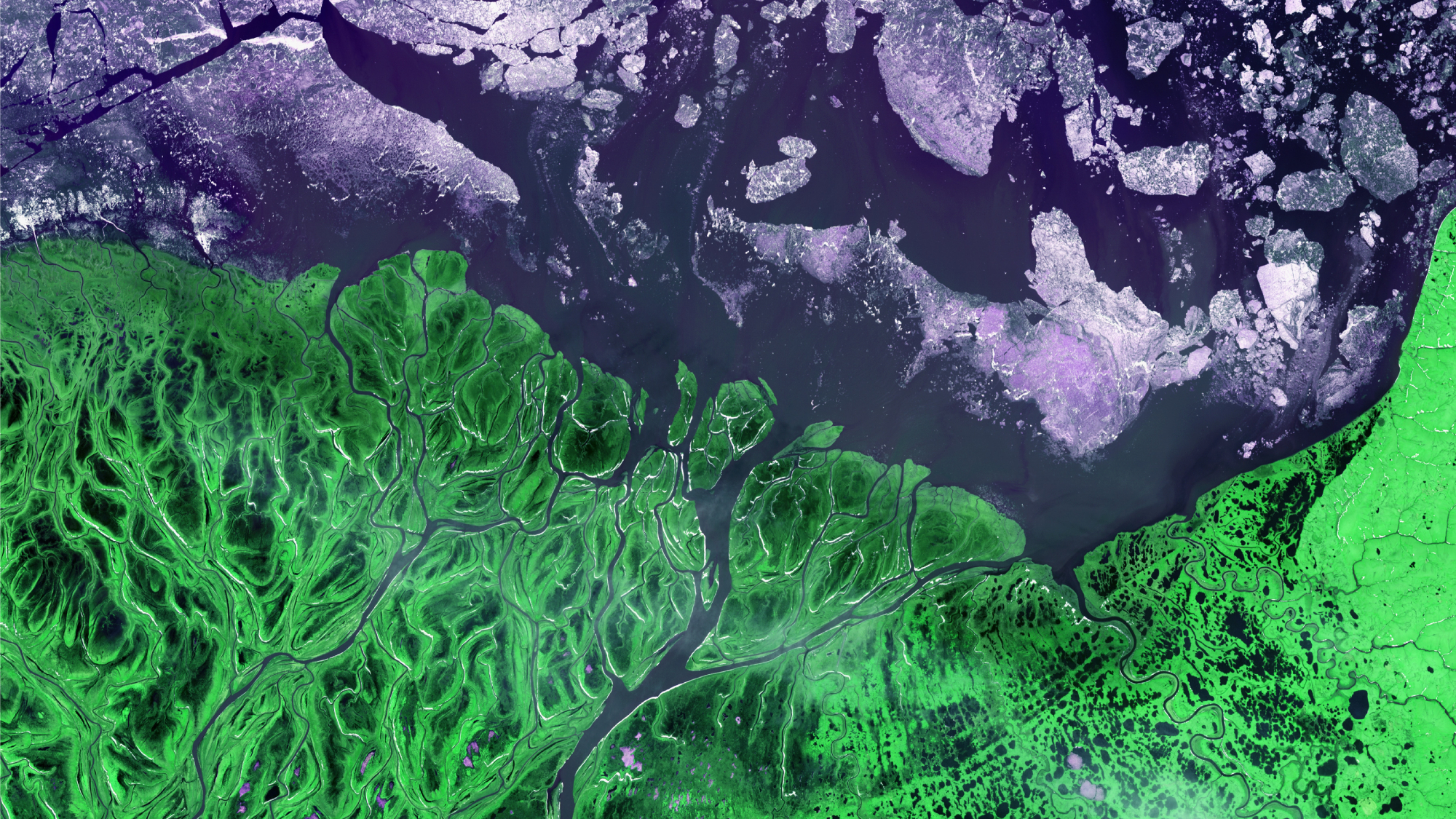

LandsatLook 2.0 now has an Imagery mode, which you can use to scroll and zoom just like a regular mapping app. This mode also gives easy access to different kinds of images—called “bands”—designed to show specific types of information.

These bands include natural color (what we think of as a satellite photo), as well as false color images to show heat, urban areas, and vegetation analysis (the density of tree and other plant cover in an area).

The control to select these is on the far right of the top menu. Click the Bands dropdown (it says Presets and Natural Color by default) and choose a different preset.

[Related: Google Street View just unveiled its new camera]

You can still view Landsat scenes by toggling between Imagery and Scenes in the top left corner of the web viewer. Scenes appear on the scrollable map as overlapping squares.

One of Landsat’s killer features is its extensive archive, which goes all the way back to 1982. Down the right side of the LandsatLook viewer, you’ll see a timeline. You can click the time-lapse button at the top of this feature to generate a series of images and either watch it play in your browser, or download it as an animated GIF.

You can select how many images are included in the GIF by clicking the Date control in the top menu. Select a start and end point from the calendar that appears, then hit Apply. If it won’t let you select a date before October 2021, this is because you’re only seeing images from Landsat 9. You can add images from the earlier Landsats by clicking the Satellites dropdown. Turn everything on to get images all the way back to 1982.

The time-lapse button is just a shortcut, by the way. You can see many more options for exporting images (or time lapses) via the Export control at the bottom left of the viewer. From the same menu bar, you can also adjust Cloud Coverage, right down to 0 percent. The viewer will filter in pixels from other images to remove the clouds.

Google Earth Engine

Google Maps has become a ubiquitous part of life for all but the most stubbornly anti-Google of us, but the big G also offers a mapping platform called Google Earth Engine (GEE). What’s the difference? Earth Engine is for organizations to develop, well, whatever they can think of using geospatial data and Google’s tech.

An example Google likes to cite is Costa Rica’s National Center for Geoenvironmental Information (CENIGA) and its early warning system for detecting illegal logging. Google provides CENIGA with data from the extensive GEE catalogue, and CENIGA’s geospatial team uses radar and visual bandwidth (that is, photographic) information to track near-real-time changes. For a country like Costa Rica which can’t afford a massive department like the USGS, with its own satellites, this stands to make a huge difference in forest management in the country.

[Related: Use Google Earth and Street View to explore the planet from your couch]

GEE isn’t just about country-scale data though. It’s a platform, which means it can scale right down to specific areas, or even specific kinds of data. For example, you might want to run a program tracking how mangroves are responding to climate change on your particular stretch of coastline. You can use data from Google, and the platform GEE provides, to put together a system that monitors just how mangrove growth is expanding or contracting as the climate changes. Google Earth Engine is one of those systems where when you ask “what can it do?” the answer is “what do you want it to do?”

A particularly big deal about GEE is that it’s free for non-commercial use, but you will need to jump through a few application hoops to get access to GEE for free. From the main application page, click Sign Up, fill out the form, and you should get approval within a week.

Planet Explorer and Planet Basemaps Viewer

When you think of a classic satellite photo, you’re likely picturing an image taken from orbit at a resolution of several meters per pixel. That’s great for regional coverage, but fine detail? Not so much.

For extreme detail, you need a commercial operator, like Planet Labs. The company flies two constellations of imaging satellites. The first, called PlanetScope, is made up of tiny Dove CubeSats which take daily images with a resolution of 30 centimeters (12 inches) per pixel. These are added to Planet’s growing archive. The second constellation, called SkySat, allows Planet to offer its customers images on demand, in a process called tasking.

The SkySats are more powerful than the CubeSats. Not only do they have a 50-centimeter-per-pixel resolution (19 inches if you need the imperial conversion), they can capture up to 90 seconds of video. That said, Planet recommends a maximum of 65 seconds for best results.

[Related: This tiny, trailblazing satellite is taking on a big moon mission]

Of course, this kind of quality doesn’t come free. How much does it cost exactly? Well, it’s complicated. Planet keeps its pricing close to its chest. However, we can get some idea of cost from third-party imagery providers such as Apollo Mapping. They charge archive packages at $5,000, and tasking packages from $15,000. These are minimum orders rather than subscriptions, and again would be tweaked depending on the client.

As for Planet itself, if you’re a student or researcher, you can apply for a Basic Account, but commercial users must deal directly with the sales department. We told you it was complicated!

You might want to hold off on a big order though, because Planet is set to upgrade its satellite constellation to a new platform called Pelican. This will consist of 32 satellites with a 30 centimeter-per-pixel resolution. That’s not quite enough to read license plates, but it’s close. Pelican will also be able to “revisit” (that is, capture multiple images) of a location up to 30 times a day, and can get you an image with as little as five minutes lead time. Again, for a substantial cost.

To play around with Planet’s in-browser Explorer viewer, you can sign up for a free 90 day trial. It includes “curated examples” of a service called My Hosted Data, which shows how you might want to use Planet Labs data for your own project or research.