This article was originally featured on The Drive.

You’ve heard the stories: Irv Gordon’s three-million-mile Volvo; Rachel Veitch had the oil in her Mercury Comet changed every 3,000 miles since 1964; a 102-year-old man drove the same car for 82 years. In the car world, we think of these rare owners as moral heroes. Whatever their reason—sentimentality? Yankee thrift? Obsessive compulsion?—they’ve sacrificed the novelty of the new for a durable relationship. They’ve won a marathon most of us don’t bother running.

I’ve been thinking a lot about long-haul car owners as we race toward a technology inflection that will upend the more than a century-old custom of car ownership. Rather than maintain their vehicles lovingly over decades, the Rachel Veitchs and Irv Gordons of the not-so-distant future—if any might still exist—will be compelled to trade them in for reasons that would have read like science fiction to car buyers of the past.

In essence, it won’t make sense to form a bond with a vehicle that’s not really yours and runs on software someone else controls.

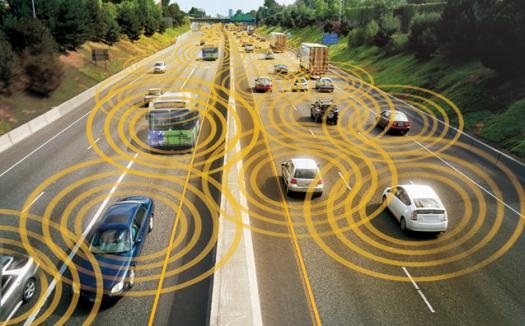

We’ve seen this coming. Over four decades, modern cars—both of the internal combustion and electric variety—have evolved from purely mechanical beasts to computing networks on wheels. That’s just the opening round. New, flexible hardware architectures developed in advance of autonomous vehicle technology, together with software ecosystems built on fast connectivity, will empower the automobile industry’s next phase: the transition from being low-margin manufacturing businesses to high-margin software businesses.

Automakers’ motivation to do that flashes every day on the NASDAQ. Tesla’s market capitalization, at around $1 trillion, now totals more than the next seven or eight top global automakers combined. Tech juggernaut Apple is possibly still (even after a ton of setbacks) working on a carmaking effort, and possibly without a traditional automaking partner. Behind every manufacturer that fails to recast itself as highly scalable, tech-forward, and disruptive—while maintaining the complex, regulated, and high-stakes “hell” work of building cars—will be a CEO on the skids. They, and more crucially, their shareholders, all want that kind of sky-high valuation Tesla has.

This is what you’d call a megatrend. In recent years Apple’s stock shot up as recurring revenue grew from zero to a quarter of its income, and the company plans to integrate subscription services even more broadly into its hardware portfolio. In the auto industry, a similar shift from a reliance on one-time vehicle sales to consistent, predictable aftersales earnings that extend into the future will coincide with the advent of the “software-defined car.”

Like smartphones, game consoles and smart appliances, cars are becoming platforms for software and harvesters of valuable user data, giving automakers a digital pipeline to their customers and allowing them to tap into a wellspring of post-purchase cash. Recently, Honda outlined its recurring revenue strategy as a technology-driven transformation of its business. “Honda will strive to transform its business portfolio,” a press release read, “by shifting focus from non-recurring hardware (product) sales business to recurring business in which Honda continues to offer various services and value to its customers after the sale through Honda products that combine hardware and software.”

“(It’s) similar to how you might think about your iPhone or Android phone,” Alan Wexler, General Motors’ senior vice president of innovation and growth told attendees of an EV investor conference last year, as reported by the Detroit Free Press, “We’re working to create experiences and services, leveraging data in the vehicles and beyond the vehicles.”

Wexler was addressing EVs specifically, but forthcoming internal combustion vehicles will be enabled similarly. In an environment where a vehicle is just another node in the Internet of Things (IoT), long-term ownership of a car might be cumbersome (or even a breach of contract), depending on how the technology evolves. Imagine trying to use an iPhone 5 you bought in 2014 without Apple’s bug fixes and security patches, which it stopped providing in 2017. Now, instead of a phone imagine a beloved SUV (which you’ve given a name) that’s slid suddenly into non-compliance.

Today, there are two forks in the car-ownership longevity story. One is the Right to Repair movement, which casts resourceful owners of cars (and, more broadly, all sorts of consumer products) against companies that use software to wall off increasingly complex systems from independent mechanics and DIY tinkerers. This is a philosophical as well as legal debate, with physical property rights slamming up against the limited rights granted via intellectual property (i.e., software) license. Although the self-reliance team won this round, the industry is not finished with them yet. The pressure for automakers to control every aspect of a new, software-focused operating environment will be significant.

The other fork involves vehicles outlasting the technologies that enable their features. That includes digital obsolescence in general and, most recently, the sunsetting of the 3G cellular network. Hundreds of thousands of car owners are now learning a hard lesson about the limitations of end-user licenses, as some of the features for which they’d paid a premium disappear, literally into thin air, with automakers under no obligation to replace them in kind.

Unlike most goods, where signing on the dotted line “exhausts” a seller’s rights while conferring them to the purchaser, the right to use software is granted to customers by license. That long document in tiny print, which we scroll past and punch the “I agree” button, spells out precisely how, where, and when a customer can use a piece of software. With the 3G case as an example—highlighting the importance of reading terms of use documents carefully—cars are joining the ranks of devices for which ownership doesn’t guarantee the right to use all features in perpetuity.

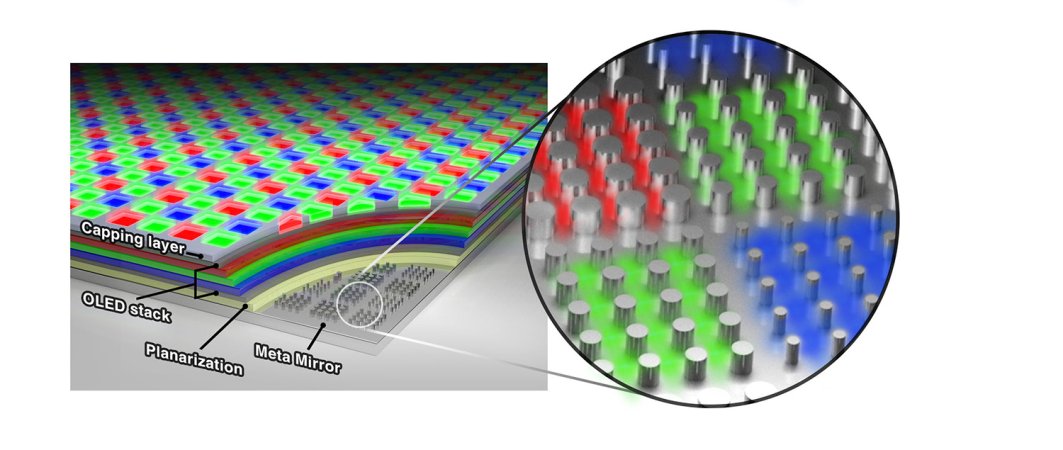

The linchpin of automakers’ new, software-first strategy is turning features into software upgrades, selling them individually or in packages, and installing them wirelessly by over-the-air (OTA) updates. GM introduced OTA software updates via its OnStar telematics service in 2009 and is working on expanding its offerings around a new hardware infrastructure. In 2012, Tesla introduced extensive OTA integration that remains central to the functionality of its EVs, including its Full Self-Driving (FSD) software. More automakers have since launched OTA functions: BMW updates its iDrive system wirelessly, as does Volkswagen with its ID range of EVs. Ford recently announced a goal to produce 33 million vehicles with OTA capability by 2028, giving it a massive addressable market for digital products.

According to McKinsey and Company, 95 percent of cars sold in 2030 will have OTA capability. As this surface of connected vehicles grows, and as consumers adapt to connected-vehicle economics, the market will evolve quickly, with more apps and services coming online, and more of a car’s features enabled (or disabled) by OTA. Although, by legal opinion, courts likely would not allow manufacturers to disable essential functions that affect a car’s intended operation—you know, as a car—anything else could be fair game for pay-as-you-go licensing: infotainment apps, comfort options like a heated steering wheel, or maybe even features that define a model’s dynamic character, like a sport sedan’s horsepower and torque parameters or suspension settings.

As the market evolves and software-platform initiatives accelerate, new, shorter-term or flexible ownership schemes that emphasize stable, predictable after-purchase revenue will heave into view. Automakers have already started experimenting with decoupling ownership from use. Car-subscription services that challenge traditional ownership may have hit the skids during the pandemic, but their story isn’t over. Call it the Netflix model for car features; even if that company’s hit a speed bump of its own, the metaphor still works. Why have a customer pay once for a car feature when they’re increasingly used to subscribing to things and you can get a recurring source of revenue from them instead?

Enthusiasts who own modern-classic cars from the past 20 years are accustomed to battling obsolescence: buying old laptops and jailbroken diagnostic software on eBay, watching YouTube for lessons on replacing bad capacitors and refurbishing degraded module chips. Will owners of the future be motivated to do the same with highly software-dependent, connected cars? Will cars become more uniform as automakers seek economies of scale, or even leave production entirely to the Magnas and Foxconns of the world? Will new models of production emerge? At the very least, as with devices, what’s coming next will separate the hackers from the rest of us.

The only questions left are how far will consumers go to preserve a traditional owning-and-driving experience, what will they sacrifice to keep it, and when will be the tipping point that kicks off widespread adoption of subscription, car sharing, fractional ownership, shared mobility, or other pay-to-drive models?

However it happens, maybe paying top dollar for a vintage, air-cooled Porsche 911 or 1980s Chevrolet C-10 pickup, or hanging on to that Corvair for another decade or two isn’t the worst idea. It may just be the ultimate future-proofing strategy.