Mining is still dangerous—but new tech in South Africa could keep workers safer

Sudden rockfall is a leading killer in the country’s hazardous mines. Are there now ways to eliminate the threat?

This article was originally published on Undark.

Thabang Ditibane spread his arms wide to describe the size of the stone that killed a fellow South African miner four years ago.

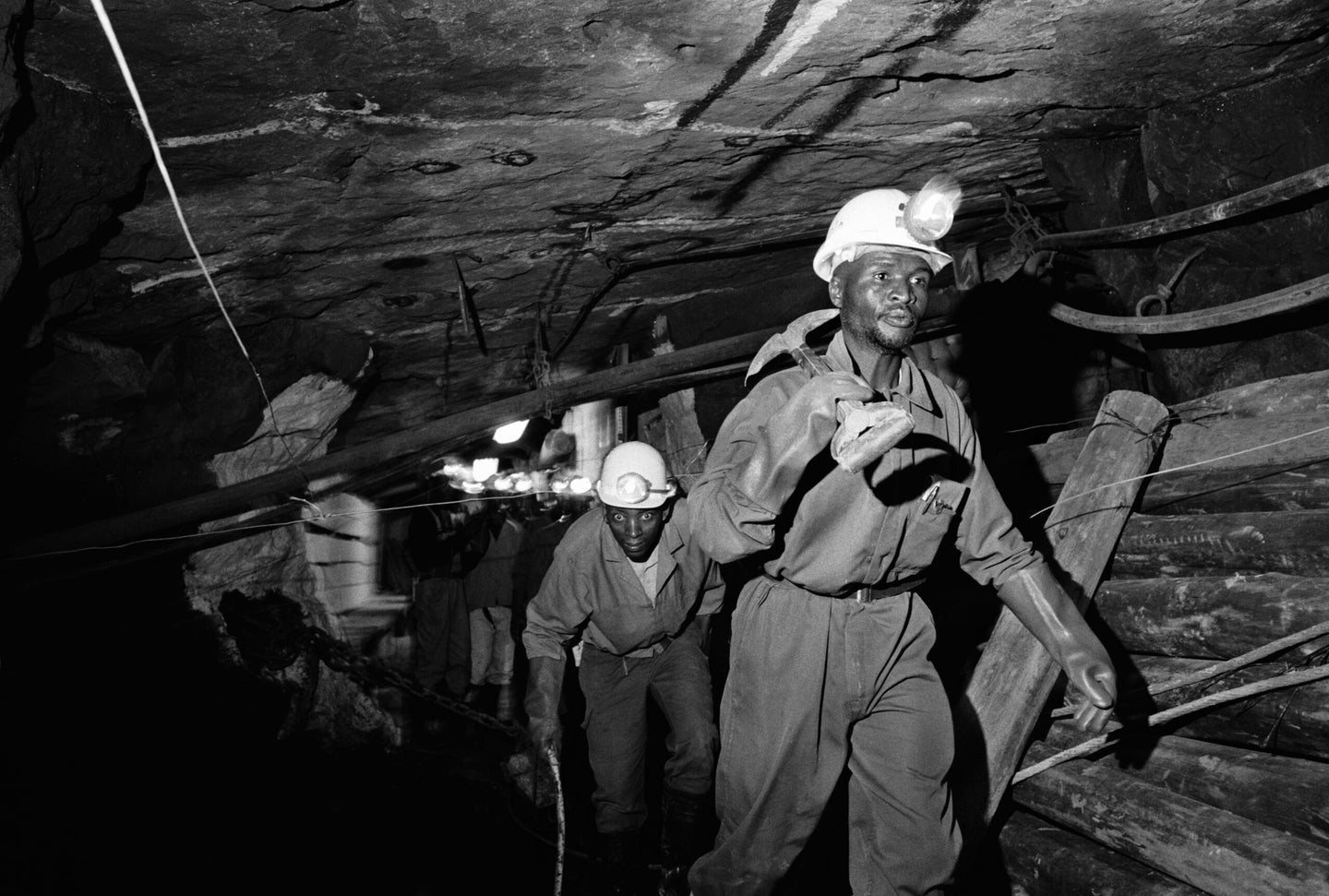

“I heard the sound and turned around, and the rock had smashed his head,” said Ditibane, a rock drill operator at the Eland mine, north of Johannesburg. As he spoke, Ditibane stood in a 6-foot high gulley, lit by a snake-like string of lights. Overhead were thousands of tons of rock.

The incident took place at another mine; the rock had suddenly collapsed into the tunnel. Such occurrences, called falls of ground, or FOGs, have long been a leading cause of accidental deaths in South Africa’s mines. According to the Minerals Council South Africa, the main industry group in the country, more than 80,000 South African miners have been killed at work since industrial-scale extraction began in the late 19th century. More than 1 million have suffered grave injuries. While the country’s record has improved significantly in recent decades, according to the International Council on Mining and Metals, an industry group, its mines are still among the most dangerous in the world.

Labor union representatives want the industry to devote more resources to improve safety. The industry is “not doing enough to invest in health and safety matters. They invest more in making profits,” said Livhuwani Mammburu, spokesperson for South Africa’s National Union of Mineworkers.

Experts say South Africa’s mines are not nearly as dangerous as they once were. Since the early 1990s, intensified regulatory scrutiny, labor activism, and investor pressure have driven the sector to mine more safely. “Zero Harm” is now the stated goal of the industry, labor organizations, and the government.

Already this year, statistics show a sharp drop in FOG fatalities. But according to some experts and industry executives, truly reaching the goal of no incidents will require new technologies, including sophisticated radars that, in theory, can detect falls of ground before they even happen. Drawing on the success of radars used on surface mines to warn about impending landslides, some experts say the new tools have the potential to drive fatalities down even further.

It’s unclear how far these tools can go. The mining sector has signaled its readiness to continue investments in research and development, but costs will be a factor in any company’s decision to adopt such technology. And geology can always spring tragic surprises underground, especially in South Africa, where ore is extracted at depths of up to nearly 2.5 miles beneath the surface.

“We will welcome any kind of technology,” Mammburu said, “that is meant to save lives in the mining industry.”

As the name suggests, a fall of ground is a terrifying prospect: The rock overhead suddenly collapses. Mining-related disturbances, gravity, and natural geological weaknesses can all play a role.

The rock mass is “not homogeneous as one would expect,” said Bryan Watson, a rock engineer at Johannesburg’s University of the Witwatersrand. Instead, he said, the seemingly solid mass is riven with joints and gaps. Molten magma pushes up from the center of the Earth and exploits the weakness, pushing it apart, Watson explained. When miners dig underneath those fissures and areas of weakened rock, he added, it creates “a void into which the rock can fall.”

Natural earthquakes can also trigger a FOG, as can small shakes triggered by mining activities near a fault line. (Such seismic events can also cause a rock burst, in which pressurized rocks explode, propelling shards at up to about 20 miles per hour.) And Watson said the blasting associated with mining, if not done properly, sometimes creates unnatural cracks from which rocks can dislodge, potentially crushing workers.

Rock drill operators like Ditibane, nearly all of whom are Black, have traditionally borne some of the greatest risks. Working in hot, cramped conditions, the miners use hydropower rock drills to bore holes into the rock face. Other miners then insert explosives into these holes, and the mine is cleared for detonation. Afterward, miners haul the rubble to the surface, where it’s processed to extract gold or platinum.A rock drill operator at Eland mine, South Africa. Netting to prevent injuries from rockfall has been installed on the tunnel’s ceiling. Visual: Ed Stoddard for Undark

During apartheid—which subjected an overwhelmingly Black, migrant labor force to ruthless exploitation—miners often worked with scant safety protections. In 1986, 800 South African miners died at work. Since the end of apartheid in 1994, South Africa’s mines have gradually become safer. Fatalities reached a record low of 51 in 2019—still almost one per week on average. During the Covid-19 pandemic, those figures rose again, although to nowhere near their apartheid levels. The leading cause of deaths are FOGs: From 2000 to 2021, rockfalls accounted for 39 percent of mine fatalities, according to Undark’s calculation from industry and government data.

Various factors have contributed to the improved safety record. Regulations passed in 1996 forced mines to implement new safety standards, and subjected them to more regular inspections.

Incentives have also shifted for many mining companies. Investors are more concerned about safety, and, at some companies, CEO compensation is now tied to safety records. Accidents can also cause mines to shut down for long periods of time as regulators investigate. “All of those costs now are being viewed as extremely serious, along with implications for the reputation of the company, but also individual reputations and performance of executives,” said May Hermanus, the former chief inspector of mines in South Africa.

Rock drill operators like Ditibane, nearly all of whom are Black, have traditionally borne some of the greatest risks.

In order to head off FOGs, mines install safety netting and bolting in the roof of underground mines. Once used selectively, the practice that has become widespread in the past decade. The premise is basic: The mesh catches loose rocks as they fall.

Recently, industry groups have acknowledged the need for more changes. In July 2021, the Minerals Council unveiled an action plan to eliminate FOG fatalities. Its analysis showed “a steep reduction in FOG fatalities between 2003 and 2011, followed by a plateauing period between 2012 and 2020.”

According to Paul Dunne, CEO of Northam Platinum Holdings Limited, there had been a deterioration in safety. “All the CEOs were unhappy about that,” he said. Dunne’s company operates three platinum mines in South Africa, and he said that falls of ground posed the highest risk. “That’s why we chose to address it.”

Now some experts are looking for an even more effective tool—a way to forecast FOGs before they even happen.

In 2013, a wall gave way at the Bingham Canyon Mine, an open-pit copper mine outside Salt Lake City, Utah. The landslide spewed 165 million tons of rock—enough, according to a team of geologists who analyzed the incident, to cover New York City’s Central Park 65-feet deep in debris. The event, they wrote, was “likely the largest non-volcanic landslide in North American history.”

But no one was there. Before the slide, a radar, developed by IDS GeoRadar, had detected increasing instability. “Mining operations were shut down the previous day in anticipation of the slide, and there were no injuries,” wrote Francesca Guerra, the marketing manager for the Italian firm, in an email to Undark.

Now IDS and other companies have been working on bringing such technology—which can detect movement without penetrating the rock—underground. IDS says the technology has been deployed worldwide, and in South Africa is being used in “special projects.”

Moving such radar underground, though, poses challenges. In particular, the radar used on surface weighs more than two tons.

The event, they wrote, was “likely the largest non-volcanic landslide in North American history.”

Recently, South African-based Anglo American Platinum has partnered with Australian technology company Geobotica to devise a hand-held underground radar.

“The idea came from the success achieved in open-pit mines using radar technology.” said Riaan Carstens, lead geotechnical engineer at Anglo. “Where it was deployed, used effectively, they pretty much eliminated fatalities from slope failure. The question was then posed: Can we use this technology in the underground space to warn people working in the vicinity of a potential fall of ground?”

Geobotica has whittled this down to a rectangular-shaped device that weighs around 7 ounces.

According to Geobotica CEO Lachie Campbell, the device generates a signal that travels through the air and bounces off the rock surface. The radar then picks up some of those reflected signals. “We send out a signal from the radar that’s in a very defined wave,” he said, “It comes back at a certain angle, and if the rock doesn’t move, that angle is always the same. But if the rock moves a little bit, it comes back at a slightly different angle.” Those slight movements, undetectable without such specialized equipment, can signal an impending collapse.

The process is called interferometry. Challenges to adapting such technology underground include power intensity.

“We create our radar signal digitally on a low-power chip, rather than using traditional radar components,” Campbell wrote in an email to Undark. The advances allow them, he wrote, to effectively shrink a 2.2 ton diesel-powered trailer system “right down to something that fits in your pocket and runs for months on a single charge.”

On a video call, Campbell provided a demonstration of how the radar, resembling a cellphone, could detect changes in his heart rate when he stopped breathing, like an electrocardiogram. Underground, the radar can filter out the movement of people to focus on the rock, Campbell said.

“This is the only way that you can forecast if a rock is going to collapse,” he said. “You need a precision that is sub-millimeter.”

IDS, the Italian company, is also trying to shrink a radar down for underground use. Their current model, called the HYDRA-U, “is designed for quick and easy transport and deployment in critical areas by one single person,” according to the company. About 4 feet high when mounted to a tripod, it is attached to a suitcase-sized power supply.

Whether such technology will find widespread use is unclear. South African mining companies said such initiatives are worth exploring, but the price tag could be an issue. “The costs involved in these advanced new technologies, we have to make sure that it is feasible,” said Jared Coetzer, head of investor relations for Harmony Gold, which manages eight underground mines in the country. “We would certainly be willing to consider all options available to assist with reducing any incidents.”

So far, the technology has received limited real-world use underground. Not everyone is convinced it will catch all FOGs. Watson, the rock engineer, said even radar was not foolproof, as geology still holds secrets.

“We don’t yet know what kind of movements are going to take place before there is a fall of ground,” he said. “How long have you got? Have you got two minutes, one hour, a day? We’re not sure.”

High-tech radar does not obscure the role that basic tools like netting and bolting can play in reducing fatalities. “There has always been a view that these falls of ground are preventable,” South African human rights lawyer Richard Spoor said in an interview. “For years the industry was skimping on roof support because it’s very expensive.”

Four FOG deaths have been recorded so far this year, according to government figures provided to Undark early last week by Allan Seccombe, head communications for the Minerals Council. That’s far fewer than the 19 on record this time last year.

Still, FOGs may have caused an undisclosed number of injuries. And South African miners are still being killed on the job in other ways: As of last week, 44 had died in accidents so far in 2022, compared to 55 in the same period last year.

“Our main, important goal is to make sure there is zero harm, there are zero injuries and zero deaths in the mining industry,” said Mammburu of the National Union of Mineworkers.