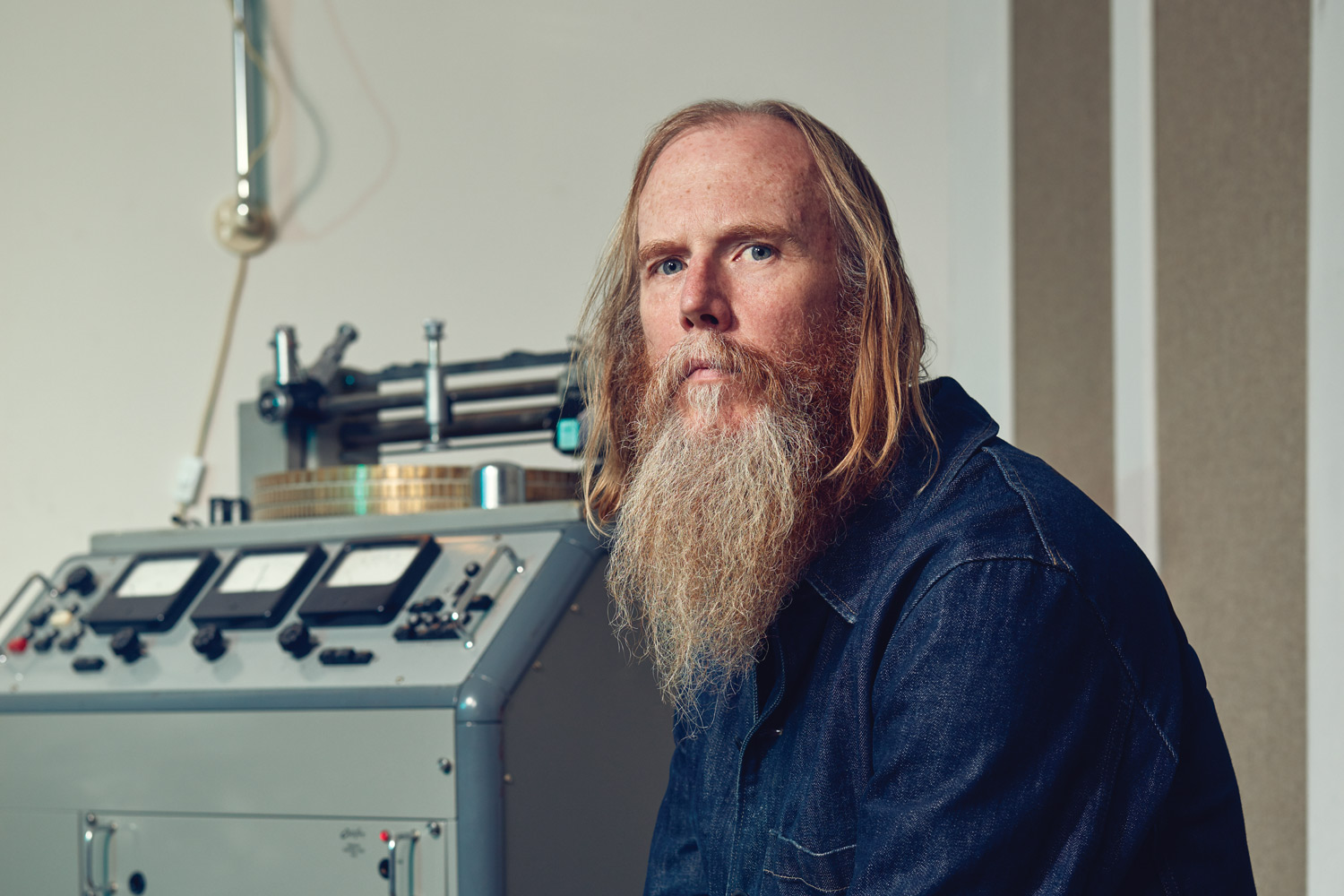

Listening to records was a reverent act in Pete Hutchison’s childhood home. Whenever his parents played their beloved Ravel and Debussy works, they enforced one rule: “You weren’t allowed to talk,” he says. Though Hutchison favored rock and jazz when he started his own collection as a teen in the 1970s, he returned to classical upon inheriting his father’s LPs. His interest in the genre eventually grew so deep that he spent $12,000 on a pristine copy of Mozart a Paris, a rare seven-disc set released in France in 1956.

Hutchison now makes what many music aficionados consider the finest records on Earth.

He meticulously crafts reissues of jazz and classical titles (including his prized Mozart) from the 1950s and ’60s—wrapped in letterpressed sleeves—that sell for $350 or more. Most labels churn out vinyl by the thousands with modern equipment, but Hutchison’s outfit, the Electric Recording Co., mints no more than 300 copies of each album. “Some of these very famous studios take the original master, and put it onto a digital system to play around with it and process it,” he says. “I don’t know why they’re bothering. They’re just degrading the sound.”

Hutchison’s methods are time-consuming: Since founding the firm in 2012, he’s produced just 41 titles. Buyers snap them up, and used copies (on the rare occasions you see them for sale) fetch several times their retail price.

While many labels cut LPs using digital files, the Electric Recording Co. favors midcentury gear Hutchison considers the best of its era. “It just sounds better,” he says. “We’ve done tests.” A reel-to-reel playback machine feeds audio from the magnetic tape of the recording session into a cutting lathe, which carves the music onto a lacquer disc. The device features a Swiss microscope that Hutchison uses to inspect his work before creating the negative, called the father, that stamps every record in the run. Most high-volume operations make copies from copies of the father, maximizing efficiency but reducing fidelity to the original.

Hutchison spent three years and well into six figures restoring the machines. “We found them in a garage in Romania with water dripping on them from the roof,” he says. Hutchison overhauled the gear with help from sound engineers Duncan Crimmins and Sean Davies, the latter of whom used it decades ago and still owned the service manuals.

Because his source material was recorded long before modern electronics, the old-fashioned equipment provides a more authentic re-creation of the original pressings. The restoration allowed Hutchison to scrutinize the sonic effect of different capacitors, resistors, wires, and, most important, the vacuum tubes that power it all. He auditioned dozens of models before choosing a set he liked. “It’s a minefield of experimentation,” he says. “And it’s a big part of what we do.”

Each record requires still more trial and error. While working on his latest project, a reissue of Way Out West by jazz saxophonist Sonny Rollins, Hutchison discovered that the original producer added reverb—the slight echo that gives music depth—during postproduction. Software can create it with a click, but Hutchison chose an analog solution: two 500-pound steel sheets, called reverb plates, that hang on springs and vibrate to the sound playing on the master tape. Electric pickups like those in a guitar capture their warbling, which he added to the recording. The hassle was worth it in Hutchison’s opinion. Anything less would be unacceptable. Just like talking while the music is playing.

This story originally published in the Noise issue of Popular Science.