This year has seen some phenomenally bizarre weather, from deadly tornadoes ripping through the Midwest and South to historic snowmelt-related flooding on the Mississippi River. Most hurricane forecasters are saying it’s about to get worse — the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration projected Thursday that the Atlantic basin is likely to see 12 to 18 named storms this season.

Amid all this, the country’s future weather prediction capabilities could be stymied by a battle in Washington.

During the budget battle earlier this spring, Congress cut funding for a new polar-orbiting satellite, which is designed to monitor atmospheric temperatures and pressure, severe weather, fires and other manmade and natural disasters, and to provide continuous climate data. If it does not get built, the country faces a satellite gap, which could affect forecasters’ ability to predict the weather.

The key word here is climate.

“Weather is apolitical, but climate is unfortunately not,” Bill Sullivan, a director at Raytheon Intelligence and Information Systems and program manager for the new satellite, said in an interview.

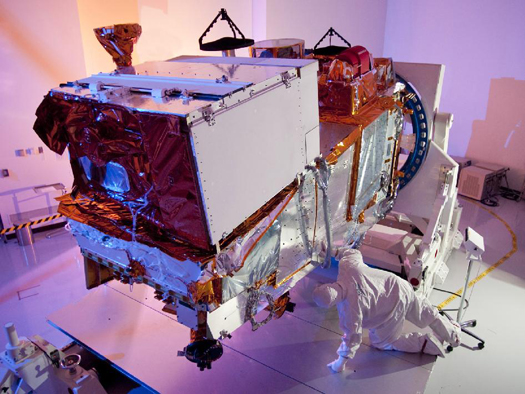

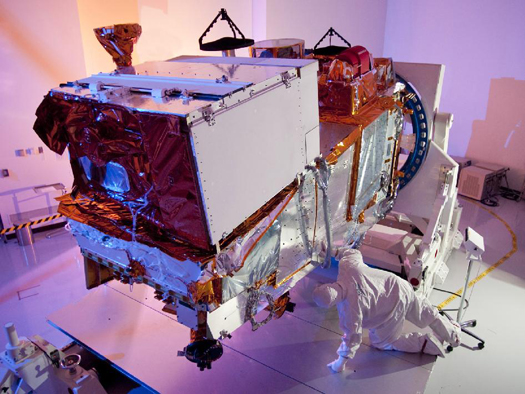

Click here to launch a gallery of images of NASA’s NPP satellite

NOAA Administrator Jane Lubchenco said at a news conference Thursday that the agency’s satellite program is in limbo.

This is at least the fourth time in the past few years that a climate-monitoring project has fallen victim to either terrible luck or bad politics. First the Orbiting Carbon Observatory failed to reach orbit, then NASA’s aerosol-monituring Glory mission also died during launch. Last month we told you about the Deep Space Climate Observatory, languishing in a box in Maryland. Now a satellite called JPSS is in danger of losing its funding.

Here’s a bit of history: Until last year, NASA, NOAA and the Department of Defense were going to share a brand-new polar-orbiting satellite called the National Polar Orbiting Operational Environmental Satellite System (NPOESS). But after a few years of planning and design work, the government decided the military and civilian agencies didn’t play well together and divorced the project, giving the DOD its own satellite. The existing civilian project, called NPP for NPOESS Preparatory Project, will serve NASA and NOAA only, and is planned for launch in October. It just completed a thermal test.

It is supposed to have a companion successor called the Joint Polar Satellite System, and NOAA requested $1.06 billion in this year’s budget to build it. Then the federal budget stalemate happened, and everything was funded at 2010 levels as Congress and the White House wrangled.

“The message that was getting to Congress was that NOAA needed a billion dollars to do climate research,” said Sullivan, who is Raytheon’s program manager for the JPSS. As a result, the funding was not approved.

Since the funding cuts, NOAA — and contractors like Raytheon — have started marketing the satellite’s weather forecasting abilities, not just its utility in informing climate models.

Polar-orbiting satellites can provide global weather coverage, which is useful when trying to make future weather predictions. Geostationary satellites, like the ones that provide the satellite radar imagery on your local news, only look at a specific section of the planet. The National Weather Service needs both sets of data to complete accurate forecasting.

NPP is a new polar-orbiting satellite that will replace NOAA’s previous orbiters, Sullivan said. It will circle the Earth 512 miles above the surface, completing about 14 orbits every day.

“We’re going to see just a huge increase in the amount of data that can be collected … NPP provides an enormous amount of capability that is currently not on orbit,” Sullivan said.

NPP will have a life span of about five years, at which point JPSS should be ready to replace it. Sullivan said NOAA needs funding this year for construction so the JPSS project doesn’t fall behind schedule. NOAA is hoping the project will get funding this year, but it looks doubtful, Sullivan said. Meanwhile, the agency is preparing for a budget battle next year, he said.

“If the program doesn’t get funded at the appropriate level in 2012, it will fall behind, which is bad for all of us,” he said.

“Not having satellites and not applying their latest capabilities could spell disaster,” said NOAA’s Lubchenko. “We are likely looking at a period of time a few years down the road where we will not be able to do severe storm warnings and long-term weather forecasts that people have come to expect today.”