Medical images are crucial to saving lives. Health care experts use X-rays, ultrasounds, and more to uncover secret maladies and confirm that organ systems are up to speed. But what if they need to go deeper, to the cellular level, to dig into a biological mystery? For those cases, scientists turn to microscopy to take sharp, detailed photographs through 10x or 100x lenses. Or they rig their own setups with tools from their labs.

The 2020 MIT Koch Institute Image Awards speak to that innovative spirit by highlighting artful, unique points of view in science. The selections aren’t just focused on medicine: Aquatic critters, nanoflowers, and cell-on-cell drama also share the spotlight. But the array of photos on cancer and brain research strike a chord, effectively demonstrating the biggest challenges—and possibilities—in understanding how life works.

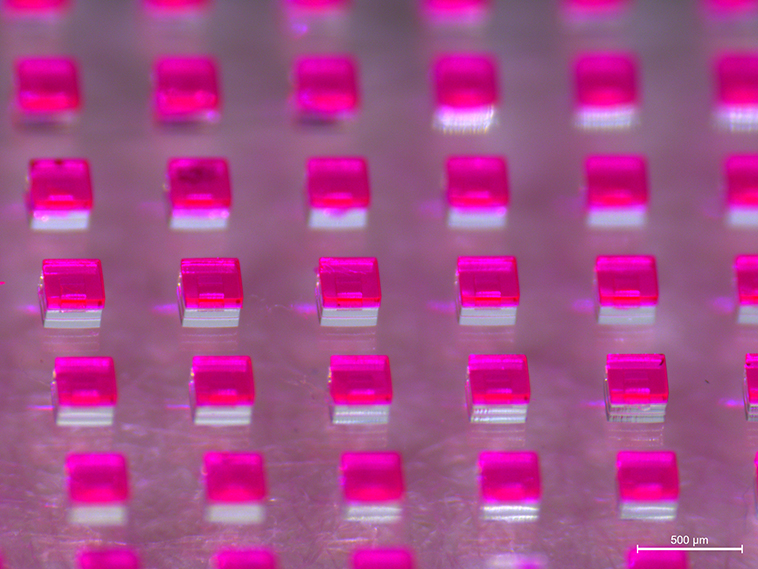

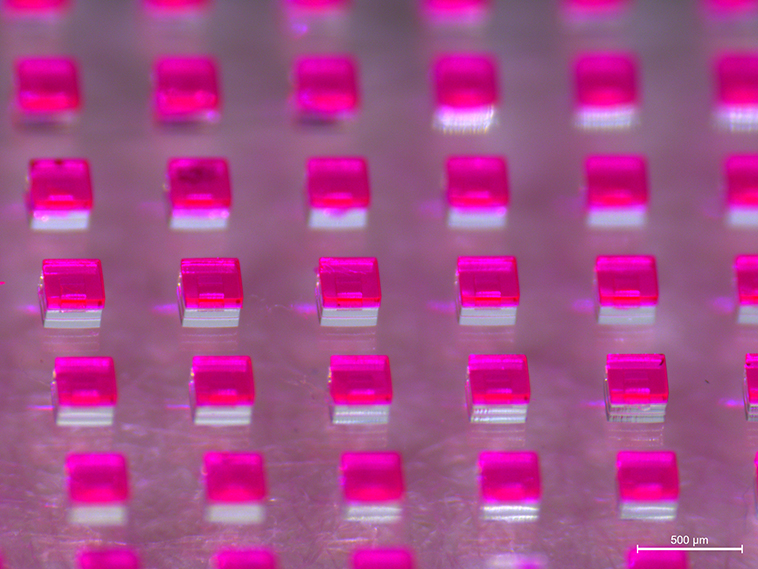

Consolidating vaccines (above)

Offering local delivery once every three days for up to six months, these hollow microparticles could really pack a punch against cancer. The Jaklenec group in the Langer Lab at MIT is modifying the microfabricated capsules—originally created as a single-shot vaccine delivery system—to accommodate the co-delivery of chemotherapy with other treatment approaches such as immunotherapy or gene therapy. They took the image to understand the mechanism behind the cargo’s release. The pink color comes from the red dye being used as a proxy for the combination of interest.

Ranking chemotherapy

How do individual gene alterations affect a tumor’s response to treatment? Each column in the grid represents a single cell line’s vulnerability to 21 different cancer drugs (one per row), out of more than 200 tested. Blue and green show sensitivity while red and pink show resistance—the cooler the color, the more likely a cell with that mutation is to be killed by that drug. The combined data present a series of “signatures” that the Hemann Lab at MIT can use to identify how drugs work and in which patients they can be most effective.

Building a neural network

Like children in gym class, young brain cells pull themselves up a rope-like fiber to form a neuronal network. Near the hollow, fluid-filled ventricle (lower left) teardrop-shaped neurons are undifferentiated, having recently split off from their mother cells. As they migrate outward toward the cortical plate, leapfrogging over one another, they mature and anchor near the pial surface (blue and green) to assume their final positions in the developing brain. Walsh Lab researchers at MIT created this architectural map to better understand how a cell’s position and lineage influence its fate.

Growing cancer cultures

The Yilmaz Lab at MIT uses miniature organs, known as organoids, to study the events leading to tumor initiation. Cells are taken from the large intestine and genetically modified to manifest common cancer-associated mutations. Seeding the engineered organoids (large white spheres) side by side with non-mutated colon organoids (blue and green) allows researchers to track and compare their growth in three dimensions. Changing the growth conditions or introducing therapeutics into the co-cultured system will help the team identify the earliest possible interventions to limit cancer progression.

Scanning lymph nodes

The objects seen here are lymph nodes—organs where immune cells learn how to respond to health threats. The Irvine Lab at MIT studies ways to target delivery of antigens and other biological training materials to the lymph nodes so that the immune system can best make use of them. This imaging experiment allows researchers to “see” the amount of antigen (red shows more, blue shows less) that gets into each lymph node, helping to identify the most effective vaccination approaches. These findings could aid in the design of new technologies for diseases that do not yet have working vaccines, such as HIV and cancer.

See all the winning images from the MIT Koch Institute Image Awards here.