What time is it on the moon?

Well, right now, that’s somewhat a matter of interpretation. But humanity is going to need to get a lot more specific if it intends to permanently set up shop there. In preparation, NASA is aligning its clocks in preparation for the upcoming Artemis missions. On Tuesday, the White House issued a memo directing the agency to establish a Coordinated Lunar Time (LTC), which will help guide humanity’s potentially permanent presence on the moon. Like the internationally recognized Universal Time Zone (UTC), LTC will lack time zones, as well as a Daylight Savings Time.

It’s not quite a time zone like those on Earth, but an entire frame of time reference for the moon.

As Einstein famously noted, time is very much relative. Most timekeeping on Earth is tied to Coordinated Universal Time (UTC), which relies on an international array of atomic clocks designed to determine the most precise time possible. This works just fine in relation to our planet’s gravitational forces, but thanks to physics, things are observed differently elsewhere in space, including on the moon.

“Due to general and special relativity, the length of a second defined on Earth will appear distorted to an observer under different gravitational conditions, or to an observer moving at a high relative velocity,” Arati Prabhakar, Assistant to the President for Science and Technology and Director at the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTB), explained in yesterday’s official memorandum.

Because of this, an Earth-based clock seen by a lunar astronaut would appear to lose an average of 58.7 microseconds per Earth day, alongside various other periodic variational influences. This might not seem like much, but it would pose major issues for any future lunar spacecraft and satellites that necessitate extremely precise timekeeping, synchronization, and logistics.

[Related: How to photograph the eclipse, according to NASA.]

“A consistent definition of time among operators in space is critical to successful space situational awareness capabilities, navigation, and communications, all of which are foundational to enable interoperability across the U.S. government and with international partners,” Steve Welby, OTSP Deputy Director for National Security, said in Tuesday’s announcement.

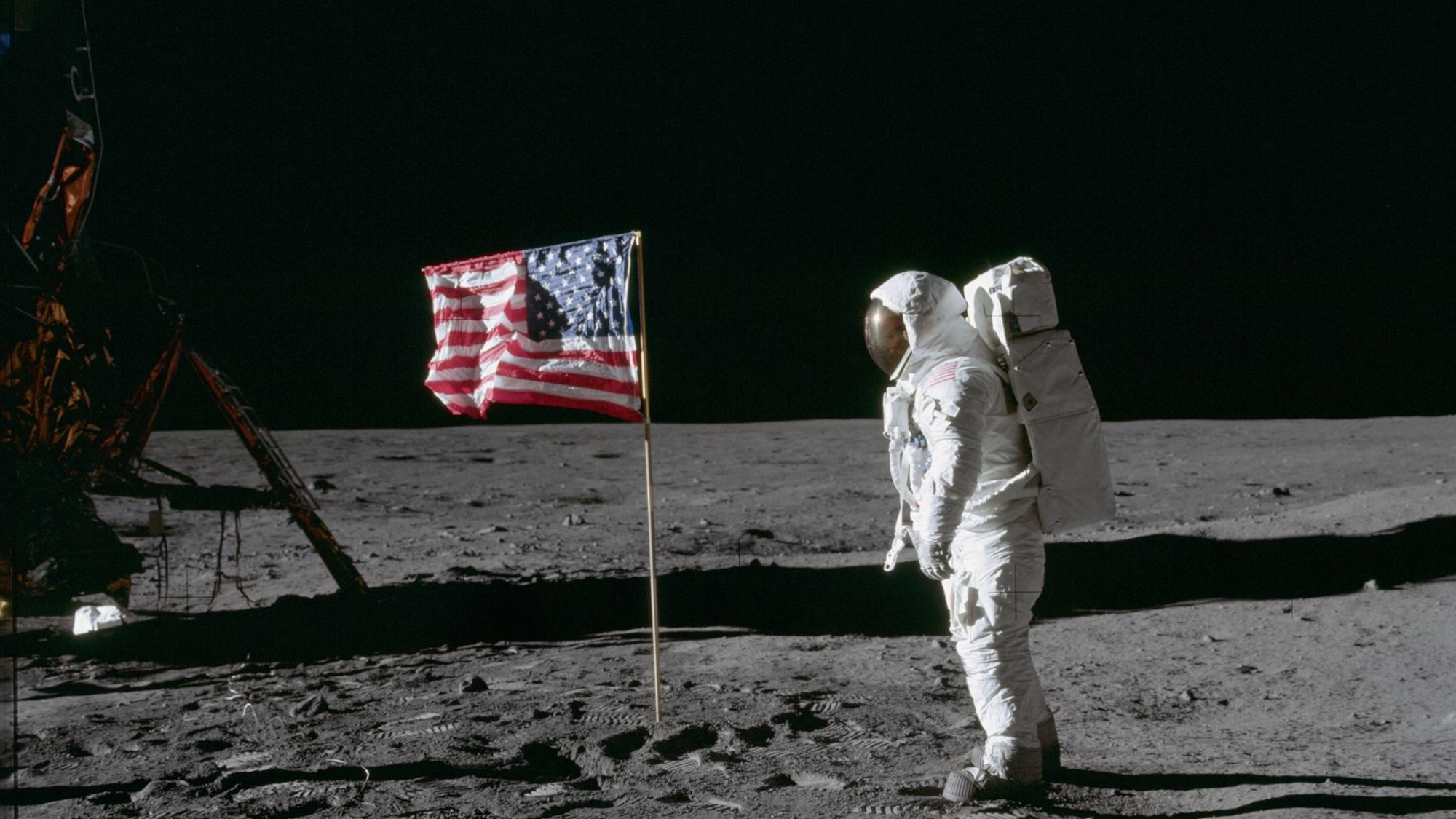

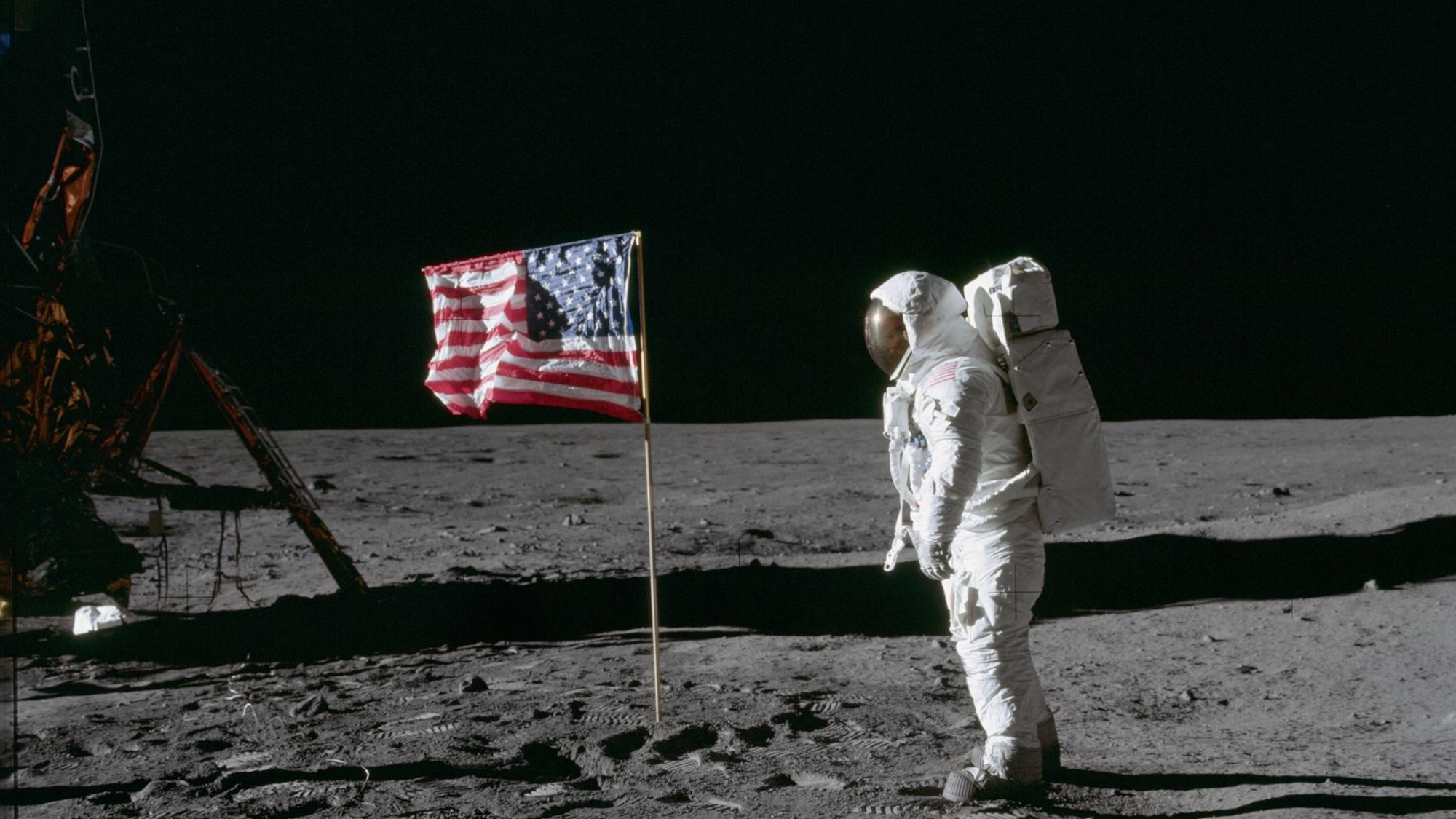

NASA’s new task is about more than just literal timing—it’s symbolic, as well. Although the US aims to send the first humans back to the lunar surface since the 1970’s, it isn’t alone in the goal. As Reuters noted yesterday, China wants to put astronauts on the moon by 2030, while both Japan and India have successfully landed uncrewed spacecraft there in the past year. In moving forward to establish an international LTC, the US is making its lunar leadership plans known to everyone.

[Related: Why do all these countries want to go to the moon right now?]

But it’s going to take a lot of global discussions—and, yes, time—to solidify all the calculations needed to make LTC happen. In its memo, the White House acknowledged putting Coordinated Lunar Time into practice will need international agreements made with the help of “existing [timekeeping] standards bodies,” such as the United Nations International Telecommunications Union. They’ll also need to discuss matters with the 35 other countries who signed the Artemis Accords, a pact concerning international relations in space and on the moon. Things could also get tricky, given that Russia and China never agreed to those accords.

“Think of the atomic clocks at the US Naval Observatory. They’re the heartbeat of the nation, synchronizing everything,” Kevin Coggins, NASA’s space communications and navigation chief, told Reuters on Tuesday. “You’re going to want a heartbeat on the moon.”

NASA has until the end of 2026 to deliver its standardization plan to the White House. If all goes according to plan, there might be actual heartbeats on the moon by that point—the Artemis III crewed lunar mission is scheduled to launch “no earlier than September 2026.”