An archive of international art is headed to the moon this year. The project, called the Lunar Codex, brands itself as “a message-in-a-bottle to the future, so that travelers who find these time capsules might discover some of the richness of our world today.” It will contain contemporary art, poetry, magazines, music, film, podcasts and books by 30,000 artists, writers, musicians and filmmakers from 157 countries.

The project is run by Incandence, a private company that owns the physical time capsules, the archival technology used in the capsules, and related trademarks, and was thought up by Canadian scientist and author Samuel Peralta, who is the executive chairman of Incandence.

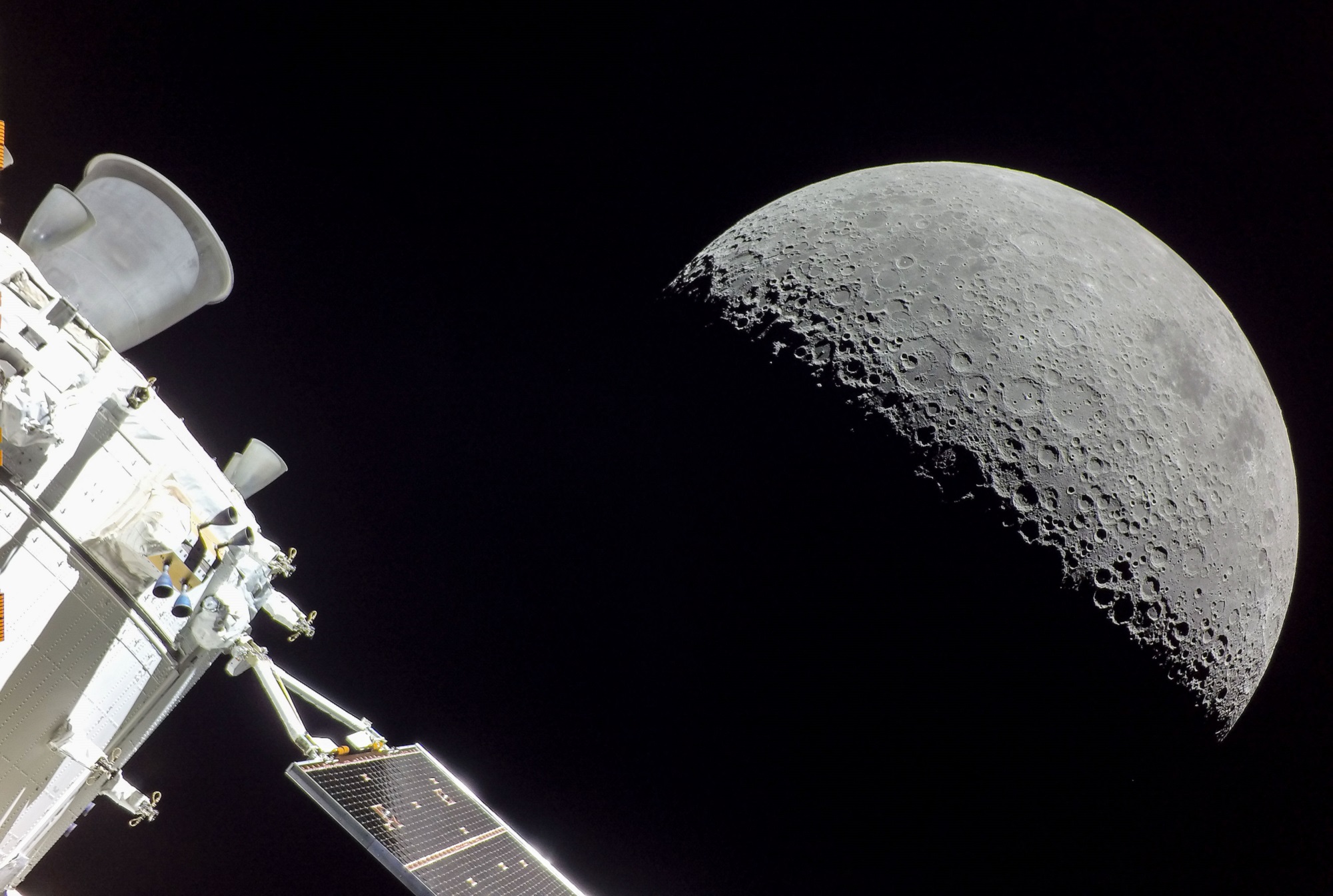

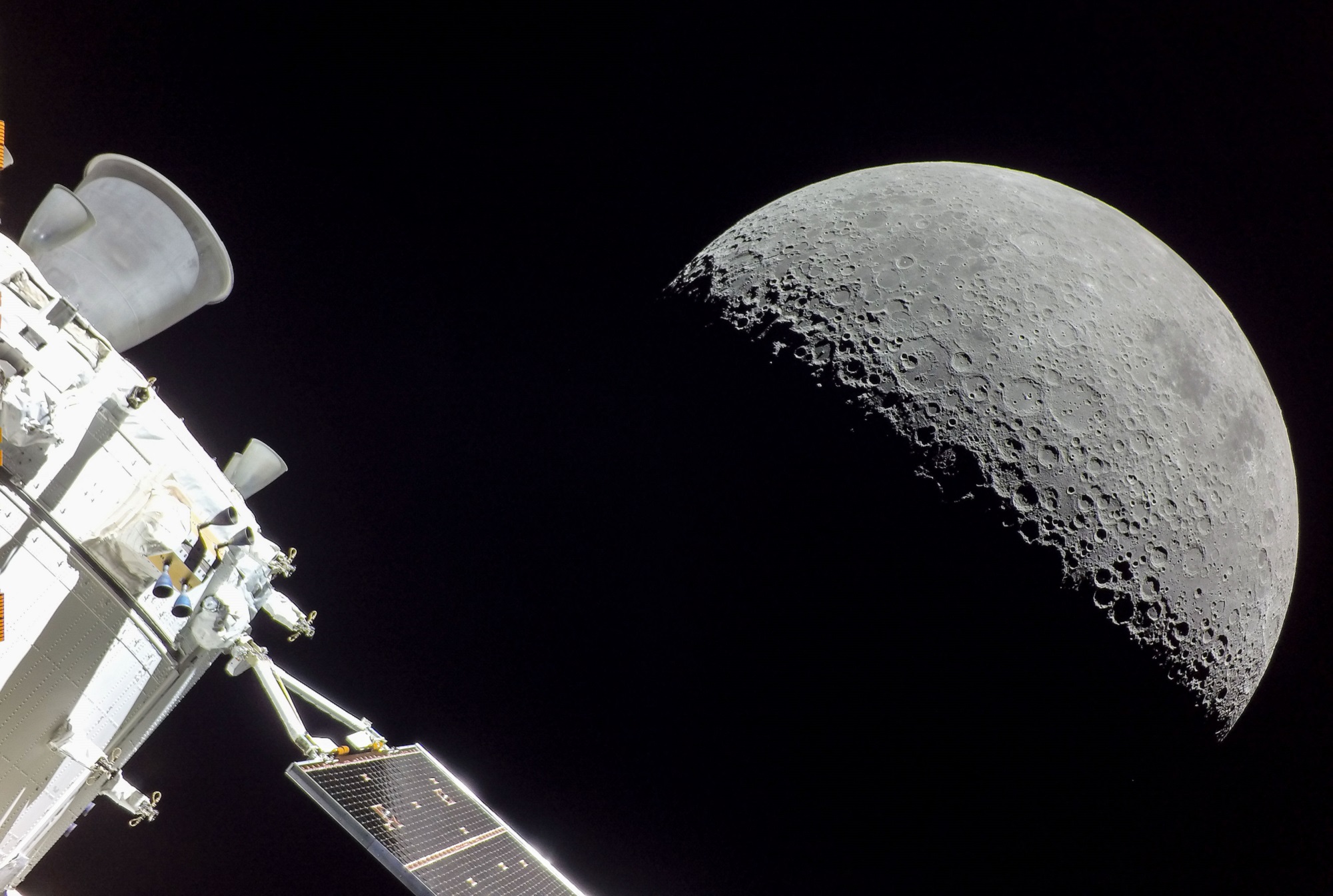

From 2023 to 2026, in a parallel mission with the Artemis launches, NASA will not only send scientific instruments to the moon, but also carry commercial payloads from partners. Peralta, in July 2020, purchased payload space from Astrobotic Technology, reserving it for the time capsules that would make up the Lunar Codex. Then the submissions rolled in. Artists do not have to pay to be considered, but the works that make it in have all been hand-selected.

If all goes according to plan, the project will be a permanent installation on the moon, sitting within a MoonPod onboard the lunar lander for the Astrobotic Peregrine Mission 1 scheduled to launch later this year. The team plans to send multiple collections via multiple launches on rockets from SpaceX and the United Launch Alliance.

Such a message requires an equally enduring medium. The one chosen by Lunar Codex is NanoFiche—a nickel-based material that etches shrunken down versions of texts and photos onto a disc-like surface. According to Lunar Codex, a single disc, which is around 3 centimeters across, can hold hundreds of small square images, each 2,000 pixels by 2,000 pixels in size. They come in sets of three in order to portray color, one channel each for red, green, and blue.

According to Lunar Codex, each disc “can store 150,000 pages of text or photos on a single 8.5”x11” sheet. It is currently the highest density storage media in the world.” The benefit of these discs is that you can read the data easily with a microscope, or a really powerful magnifying glass, no software needed. It bypasses the difficulties many forms of digital storage have today, which is that digital data, usually kept in the form of bits, can degrade over time.

Since nickel does not oxidize, degrade, or melt (unless under extreme high temperatures), and can withstand various types of environmental factors that they might have to withstand in outer space like radiation and electromagnetic radiation, it’s the most stable, and probably cheapest form of long-term storage option. The Arch Lunar Library, an effort by the non-profit Arch Mission Foundation to preserve human culture and knowledge, also uses NanoFiche as its preferred form of storage.

[Related: Inside the search for the best way to save humanity’s data]

This kind of storage does have some limitations. For example, capturing film and music would be tedious and expensive. For film, each frame would have to be etched—a daunting task. As an alternative, screenplays or scripts are captured instead. And for music, it’s represented as sheet music or hex-encoded MIDI files.

The Lunar Codex is also experimenting with another way to archive music, by etching their waveform and frequency spectrograms onto NanoFiche. “The original music may be reconstructed via sound wave analysis algorithms,” Peralta explains on the website.

Of course, The Lunar Codex isn’t the first project to set foot on the moon. Other than the Arch Mission Foundation’s Lunar library, and an assortment of miscellaneous human trash left behind, there’s also “The Moon Museum” which arrived with Apollo 12 in 1969. It was an etched ceramic wafer smuggled onto a lander leg.