A newly discovered asteroid is a toddler–in space years. The moonlet circling the small asteroid Dinkinesh named Selam is about 2 to 3 million years old. Scientists arrived at this age estimate using new calculation methods that are described in a study published April 19 in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

Selam is nicknamed “Lucy’s baby,” after NASA’s Lucy spacecraft discovered it orbiting another asteroid in November 2023. The Lucy mission is the first set to explore the Trojan asteroids. These are a group of about 7,000 primitive space rocks orbiting Jupiter. Lucy is expected to provide the first high-resolution images of these space rocks. Dinkinesh and Selam are located in the Main Asteroid Belt between Mars and Jupiter.

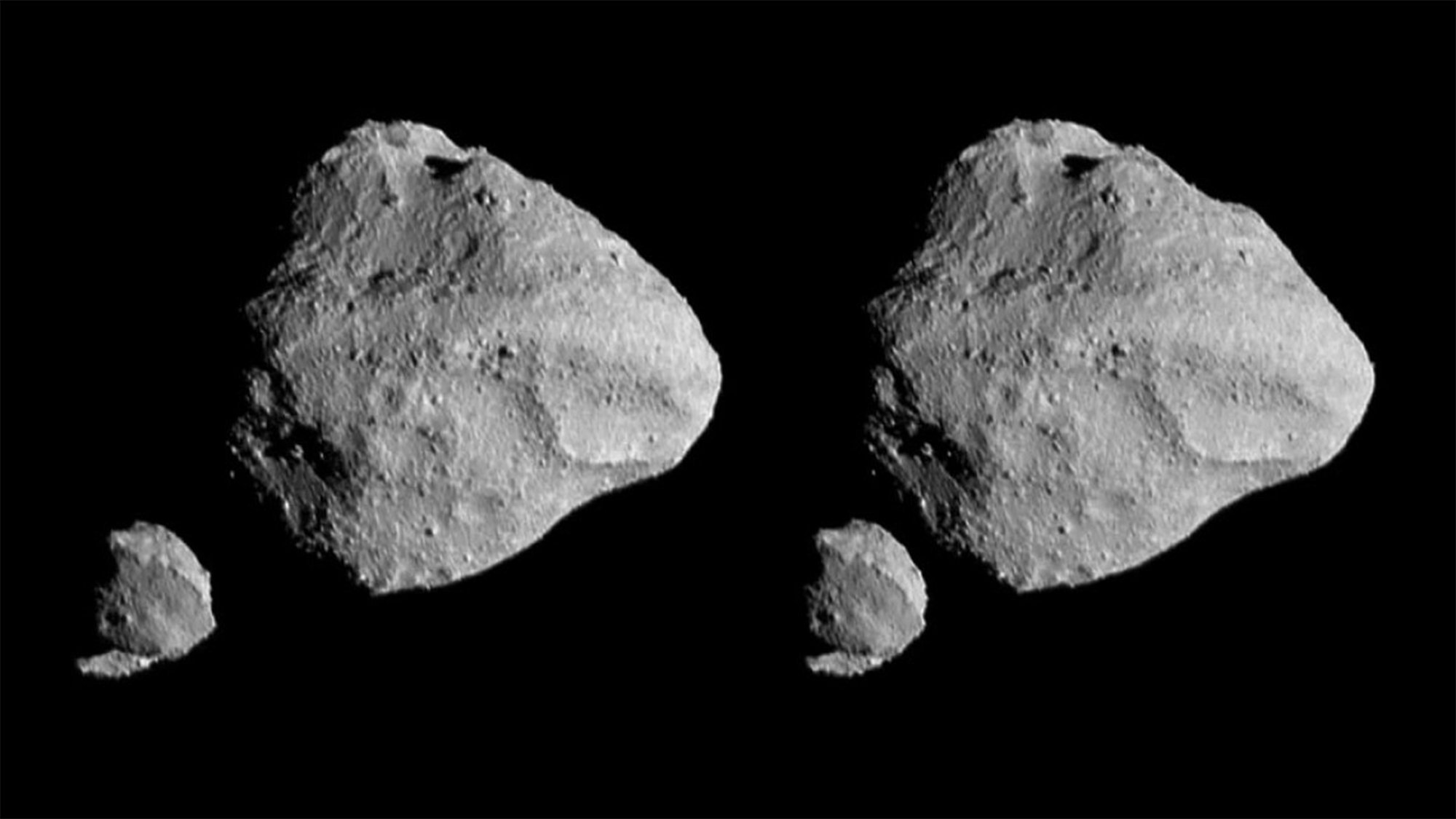

Discovering a tiny moonlet was a surprise. According to study co-author and Cornell University aerospace engineering doctoral student Colby Merrill, Selem turned out to be “an extraordinarily unique and complex body.” Selem is a contact binary that consists of two lobes that are piles of rubble stuck together and is the first of this kind of asteroid ever observed. Scientists believe that Selam was formed from surface material ejected by Dinkinesh’s rapid spinning.

[Related: NASA spacecraft Lucy says hello to ‘Dinky’ asteroid on far-flying mission.]

“Finding the ages of asteroids is important to understanding them, and this one is remarkably young when compared to the age of the solar system, meaning it formed somewhat recently,” Merrill said in a statement. “Obtaining the age of this one body can help us to understand the population as a whole.”

To estimate its age, the team studied how Dinkinesh and Selam moved in space–or its dynamics. Binary asteroids like this pair are engaged in a galactic tug-of-war. Gravity that is acting on the objects is making them physically bulge and results in tides similar to what oceans on Earth have. The tides slowly reduce the system’s energy. At the same time, the sun’s radiation also changes the binary system’s energy. This solar change is known as the Binary Yarkovsky-O’Keefe-Radzievskii-Paddack (BYORP) effect. The system will eventually reach an equilibrium, where tides and BYORP are equally strong.

Assuming that the forces between the two were at equilibrium and plugging in asteroid data from the Lucy mission, the team calculated how long it would have taken for Selam to get to its current state after it formed. The team said that they improved preexisting equations that assumed both bodies in a binary system are equally dense and did not factor in the secondary body’s mass. Their computers simulations ran about 1 million calculations with varying parameters and found a median age of 3 million years old, with 2 million being the most likely result. This calculation also agreed with one made by the Lucy mission based on a more traditional method for dating asteroids based on an analysis of their surface craters.

According to the team, studying asteroids this way does not require a spacecraft like Lucy to take close-up images, thus saving money. It could be more accurate in cases where an asteroid’s surfaces have undergone recent changes from space travel. Since roughly 15 percent of all near-Earth asteroids are binary systems this method can also be used to study other secondary bodies like the moonlet Dimorphos. NASA deliberately crashed a spacecraft into Dimorphos to test out planetary defense technology in September 2022.

[Related: NASA’s asteroid blaster turned a space rock into an ‘oblong watermelon.’]

“Used in tandem with crater counting, this method could help better constrain a system’s age,” study co-author and Cornell University astronomy doctoral student Alexia Kubas said in a statement. “If we use two methods and they agree with each other, we can be more confident that we’re getting a meaningful age that describes the current state of the system.”