Summertime may be the right time for unmasking dark matter. Researchers working on a dark matter experiment buried half a mile underground in a Minnesota mine say they’ve seen seasonally varying blips in electrical pulses that may be the telltale signs of WIMPs, or weakly interacting massive particles.

If they’re accurate, the new findings would back up previous research from an underground lab beneath a central Italian mountain, which has proved controversial for nearly a decade.

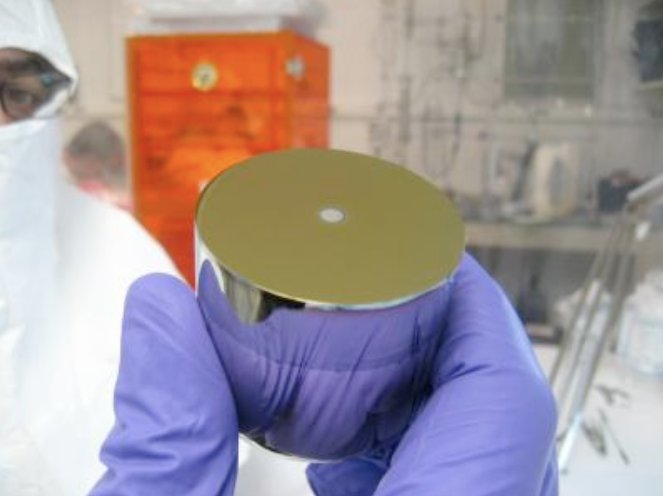

The new result comes from the Coherent Germanium Neutrino Technology (CoGeNT) experiment at Minnesota’s Soudan mine, where detectors are looking for the faintest interaction between WIMPs and atoms inside a germanium crystal. Researchers led by Juan Collar at the University of Chicago’s Kavli Institute for Cosmological Physics studied about 15 months of data — not very much, but they were interrupted by a fire in March.

They saw signs of a seasonal variation in the interactions between WIMPs and germanium crystals, according to the Kavli Institute. It’s not a WIMP signal per se, but it’s what you would expect to see from a WIMP signal, Collar said. WIMPs are thought to be particles of dark matter, which makes up about 23 percent of the universe.

It’s hard to see these ineffable particles because they do not interact with the electromagnetic or strong nuclear forces. This is one reason why detectors are buried underground, breathing new life into old abandoned mines — thick rock layers shield the instruments from background radiation and cosmic rays that could block out a super-faint signal from a passing WIMP.

The detectors picked up an average of one WIMP interaction per day for 15 months, with a seasonal variation of 16 percent. (For a more thorough explanation of the results, read an extensive interview with Collar here.)

Along with echoing the previous Italian experiment, this fits with accepted theories of how Earth encounters dark matter clouds in our galaxy.

As Earth enters the summer portion of its orbit around the sun, its movement is aligned with the direction of the sun’s own movement in the plane of the Milky Way. This increases our planet’s net velocity through a cloud of dark matter particles that permeate the galaxy. Scientists can infer the existence of the dark matter cloud, and they know the Earth is hurtling through it, so it would make sense that we would see an increase in dark matter signals during the spring and summer. That’s what this result claims to see.

A few years ago, the DArk MAtter/Large sodium Iodide Bulk for RAre processes (DAMA/LIBRA) experiment at Gran Sasso, Italy, claimed to see the same thing. But many physicists have dismissed those findings. Then in 2009, another experiment at the Soudan mine, the Cryogenic Dark Matter Search, found the heat signatures of possible WIMPs.

In a separate paper, physicists Dan Hooper of Fermilab and Chris Kelso from the University of Chicago reviewed the data from CoGenT and DAMA/LIBRA, and said the numbers are compatible. “If the true phase peaks in early May, this would represent a modulation consistent with that reported by the DAMA/LIBRA collaboration,” they say.

Collar said the team is still working out whether their results just barely exclude DAMA’s results or just barely agree with them. Meanwhile, Hooper and Kelso said another dark matter experiment, the CRESST collaboration, is reporting findings that are also roughly consistent with the purported particle spotted by CoGeNT.

But here’s the rub: other experiments, including one in the same mine, have found no dark matter indications. So which one is to be believed?

“It’s not an exact science yet, unfortunately,” Collar said. “But with the information we have, the usual set of assumptions that we make about the halo and these particles, their behavior in this halo, things seem to be what you would expect.”

What does this mean for all of us? Physicists are getting ever closer to nailing down the nature of dark matter, one of the greatest mysteries in science. Understanding dark matter will help us understand the origin and evolution of the universe. With new, deeper mine detectors ramping up their experiments, and a new dark matter detector in space, the future of dark matter studies looks pretty bright.