Some of the greatest discoveries in science have been total accidents — Alexander Fleming’s use of penicillin, Wilson and Penzias’ discovery of the cosmic microwave background, etc. Today, scientists announced they’ve once again unintentionally made a monumental discovery: A cure for baldness. OK, only in mice.

Still, the finding — involving a chemical compound that blocks a stress hormone — could lead to human hair loss treatments, the scientists say. The researchers have applied for a patent on the use of the compound for hair growth.

“This could open new venues to treat hair loss in humans through the modulation of the stress hormone receptors, particularly hair loss related to chronic stress and aging,” said Million Mulugeta, an adjunct professor of medicine at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA.

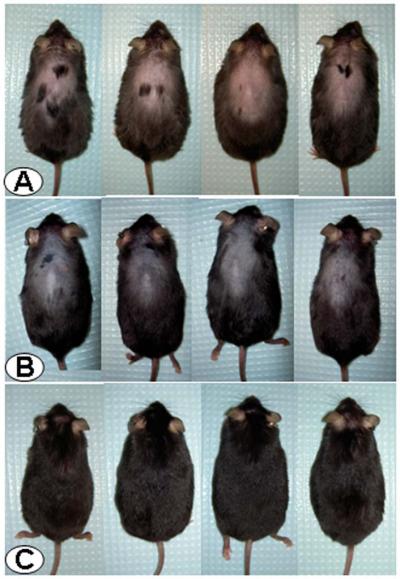

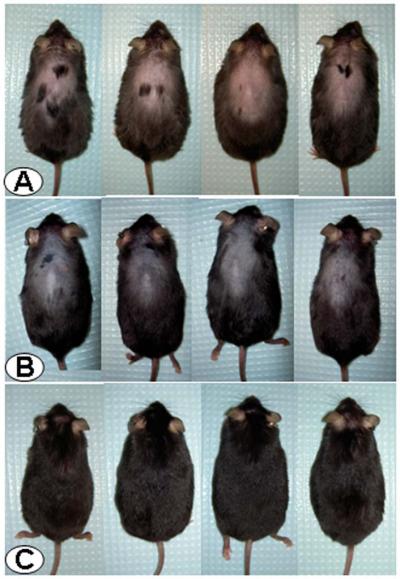

The researchers were testing the relationship between stress and the gastrointestinal tract, and after leaving the mice alone for a couple months, they found that their hair had grown back. The researchers couldn’t tell them apart from their unstressed, hirsute brethren.

The research involved teams from UCLA, the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and the Oregon Health and Sciences University. The researchers were using mice that have been genetically engineered to produce an excess of a stress hormone called corticotrophin-releasing factor, or CRF. As they age, the super-stressed mice lose hair and eventually become bald on their backs.

Researchers at the Salk Institute developed a peptide called “astressin-B”, which blocks the action of CRF, and the teams injected the peptide into the bald mice. They weren’t thinking about baldness at all — they wanted to test whether the astressin had any impact on the mice’s gastrointestinal tracts. The first injection did nothing, so the team gave the mice additional injections over five days, and then measured the effects on the newly de-stressed mice’s colons.

About three months later, the researchers came back to do some follow-up GI tests, but they couldn’t find their test mice. They had to check the creatures’ ID numbers to make sure the hairy results were real. Follow-up studies proved it without a doubt, according to a UCLA news release.

Most surprisingly, just one dose a day for five days maintained the hair-growing effect for up to four months. In the two-year lifespan of a mouse, that’s an incredibly long time, suggesting a minimal dose packs a powerful punch.

Researchers know that CRF is found in human skin, along with other peptides that modulate it, so it is possible this treatment will work in humans.

The discovery is described in an article published in the online journal PLoS One.