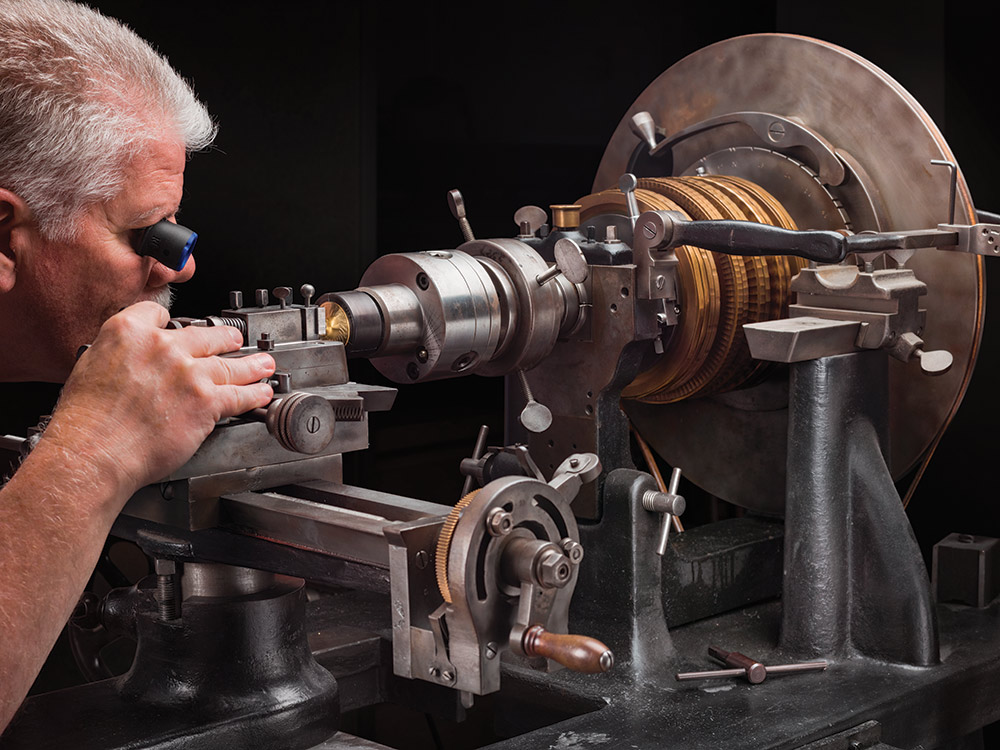

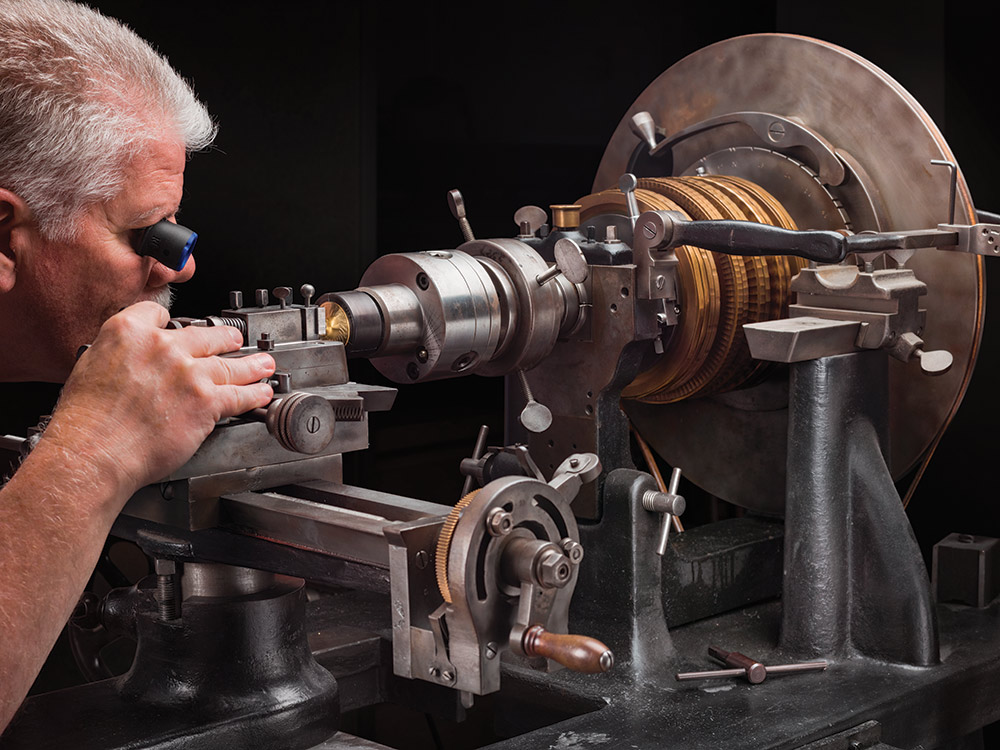

Roland G. Murphy is the R, G, and M in RGM Watches, the last American outfit manufacturing fine watches and their 100-plus-piece movements from raw, precious metals. After a part-time gig in high school that involved building clock cabinets, he caught the horological bug. Murphy went on to study watchmaking in Switzerland and then took a job developing timepieces for the Hamilton Watch Company. Twenty-five years ago he founded RGM. Here, he works a 1913 Swiss lathe called a Rose Engine.

Mount Joy, Pennsylvania, seems an unlikely location for the epicenter of high-end American horology. But Lancaster County has provenance: Hamilton once based here, and the famous Bowman Technical School watchmaking academy operated locally until 1992. Murphy attended the school and is now honing his craft in an old bank building nearby. “We bought it for the vault,” he says. Makes sense: RGM’s watches start around $3,000 and climb above $100,000.

You might hear the term “jewel”—often preceded by a number—when talking watches. It refers to these little red guys surrounded by all that gold. Though many high-end pieces do benefit from a bit o’ bling, jewel usually refers to tiny, super-hard gems inside a watch’s movement that reduce wear between metal parts. Watchmakers used to grind jewels out of actual rubies, but these days they employ synthetic gems that fit into holes reamed by this machine, which is about the size of a tissue box.

Ten people work at RGM; eight of them, including Murphy, build, repair, and fabricate watches. They work the same tools you’d find in an early-20th-century Swiss atelier. Four cast-metal engine-turning machines dominate the main workroom. These lathes carve patterns into metal surfaces. The process, known as guilloche, requires expertise that sets RGM apart.

“Guilloche is a whole separate craft from watchmaking,” says Murphy. “Very few people around the world do both.”

Watchmaker Jake Weaver-Spidel adjusts one of the company’s house- made movements, the Caliber 801. It takes about a week to assemble and adjust one of these machines, and that’s in addition to the time it takes to fabricate the components (months). Murphy purposely designs his movements with servicing in mind, so that, if cared for, they could last indefinitely. More than watches, these are heirlooms. “I don’t like the idea of building something with a life span in mind,” he says.

If there’s a flat surface inside a high-end watch, chances are it’s decorated, or, as watchmakers say, finished. The word choice speaks volumes about the craft. Even though the recessed areas of this watch’s main plate will soon sit under a multilayered complement of gears, springs, and other parts, they’re subjected to a purely decorative process called perlage. RGM’s artisans grind tiny overlapping circles over every exposed facet of the plate. It can take a half-hour or more to embellish this part.

Fancy watches are expensive for two main reasons: The first is material cost. Watchmakers groove on precious metals like gold and platinum for decorative elements outside the movement, which is typically made from steel, nickel, silver, or brass. The other, much more significant factor is labor. RGM produces only around 60 watches with what are known as in-house movements in a given year. Murphy’s team fastidiously crafts these beating watch hearts by hand.

This article was originally published in the September/October 2017 Mysteries of Time and Space issue of Popular Science.