At its closest point, the western coast of Canada is more than 7,000 miles away from the edge of Australia. But the world map hasn’t always been that way.

Researchers at Curtin University in Australia published a study in Geology which found that more than a billion years ago, a chunk of present-day Canada broke away from the fledgling North American continent and smashed into Australia. That chunk of land is present-day Georgetown, Australia.

The collision produced a mountain range in northern Australia, although a relatively small one. The same type of landmass collisions created the Himalayas in India, but with much greater force, creating a larger range that’s still growing taller today.

The researchers at Curtin looked at new sediment data from Georgetown and the neighboring regions, and realized that the rock record didn’t match the rest of the Australian continent. But it did match areas of Canada, which is why the paper hypothesizes that two distinct land masses collided.

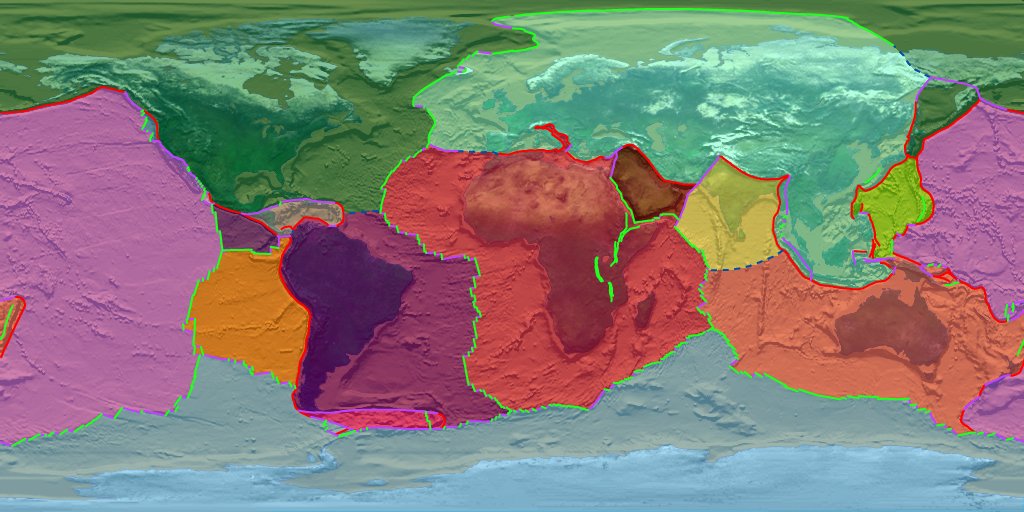

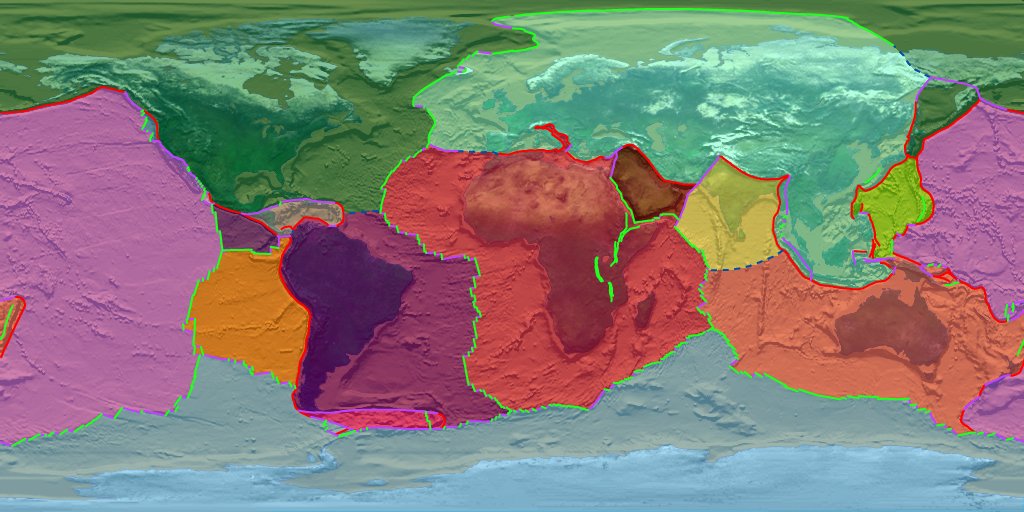

“This new finding is a key step in understanding how Earth’s first supercontinent Nuna may have formed,” Zheng-Xiang Li, one of the study’s co-authors, said in a press release. The Earth’s crust, which contains its land masses and the ocean floors, isn’t static—it’s made up of plates that shift, slide, and collide. Think of each plate like a puzzle piece, except that the pieces can overlap and move, and there isn’t one correct alignment. Because those plates are always moving, the arrangement of continents and oceans has been in flux over the last several billion years.

The seven distinct continents we know and love today are thought to have started off as one, giant landmass called Pangea nearly 300 million years ago. Eventually, the land mass broke apart as plates shifted, pulling pieces of the supercontinent in different directions. You might recall some of this from your elementary school science class.

Nuna is like the older sibling of supercontinents: it existed way before the more well-known land mass of Pangea, but it gets less attention. Nuna, also known as Columbia, was smashing land masses together and reconfiguring the surface of the Earth some 1.5 billion years ago. For perspective, the earliest humans are thought to have existed just two million years ago.

The older a supercontinent is, however, the harder it is to find concrete evidence of its existence. The theory of Pangea rests on fossil records that seem to skip over modern day oceans, indicating that the ocean didn’t exist at the same time as these now-fossilized critters. But the fossil record is less detailed the further back you dig, making it harder to find proof of older supercontinents.

This is the second major geological discovery coming out of Oceania in about a year: last February, researchers based in New Zealand published findings which suggest the island country is really a massive underwater continent.

These discoveries, that uncover billion-year old events in Earth’s history, are all the more impressive considering that as recently as the 1960’s, they might not have been accepted as legitimate science. The theory of plate tectonics only became a mainstream field of study about fifty years ago. In geological years, that’s nothing.