In the summer of 2015, researchers at Google realized they could make their artificial intelligence algorithms dream. They set the programs to not just classify images, but enhance what they saw. The machines showed their interpretation of art.

The researchers found they could also set the programs to generate images, giving an idea of how the machine thought certain objects looked. This discovery came on the rising tide of the idea that machines could be creative tools.

Nearly a year later, Google is announcing Project Magenta, a exploratory group that will experiment with creativity and artificial intelligence. The team will focus on making art in various forms—they’ll first focus on music, and then move to video and other visual media.

“With Magenta, we want to explore the other side—developing algorithms that can learn how to generate art and music, potentially creating compelling and artistic content on their own,” writes Douglas Eck in the Magenta blog‘s first post.

The first project released with Magenta is a simple song based on the four first notes of “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star,” made by Google researcher Elliot Waite. The song is just a digital piano tinkering with notes that starts out simple, but then becomes increasingly complex and nuanced. There are even a few honestly good musical phrases. (The drums were added later by a human.)

Artistic Intelligence

Researchers have been trying to crack artificial intelligence that makes creative choices since the dawn of the practice. Marvin Minsky, seen as a father of modern A.I. research, wrote in 1960, “I am confident that sooner or later we will be able to assemble programs of great problem-solving ability from complex combinations of heuristic devices—multiple optimizers, pattern-recognition tricks, planning algebras, recursive administration procedures, and the like. In no one of these will we find the seat of intelligence.”

There’s more to intelligence than just recognizing patterns, but finding that “seat” of intelligence is tricky, and has vexed artificial intelligence researchers and psychologists alike.

Martine Rothblatt, founder of Sirius XM, futurist author, and commissioner of her robotic partner Bina48, says that to be truly creative, machines must be capable of creating more than just random samplings of things they’ve seen before.

“The most important element is idiosyncrasy. If you write a program that just randomly mixes elements, that’s not creative,” Rothblatt told Popular Science at Moogfest. “A lot of it is in the eye of the beholder. If it feels unique, it will feel creative.”

Thousands of projects attempting to meet this threshold of “feeling” creative and novel have been undertaken, particularly in visual art and music generation. They attempt to recapture how Picasso would paint a 21st century scene, or Beethoven’s bombastic sensibilities.

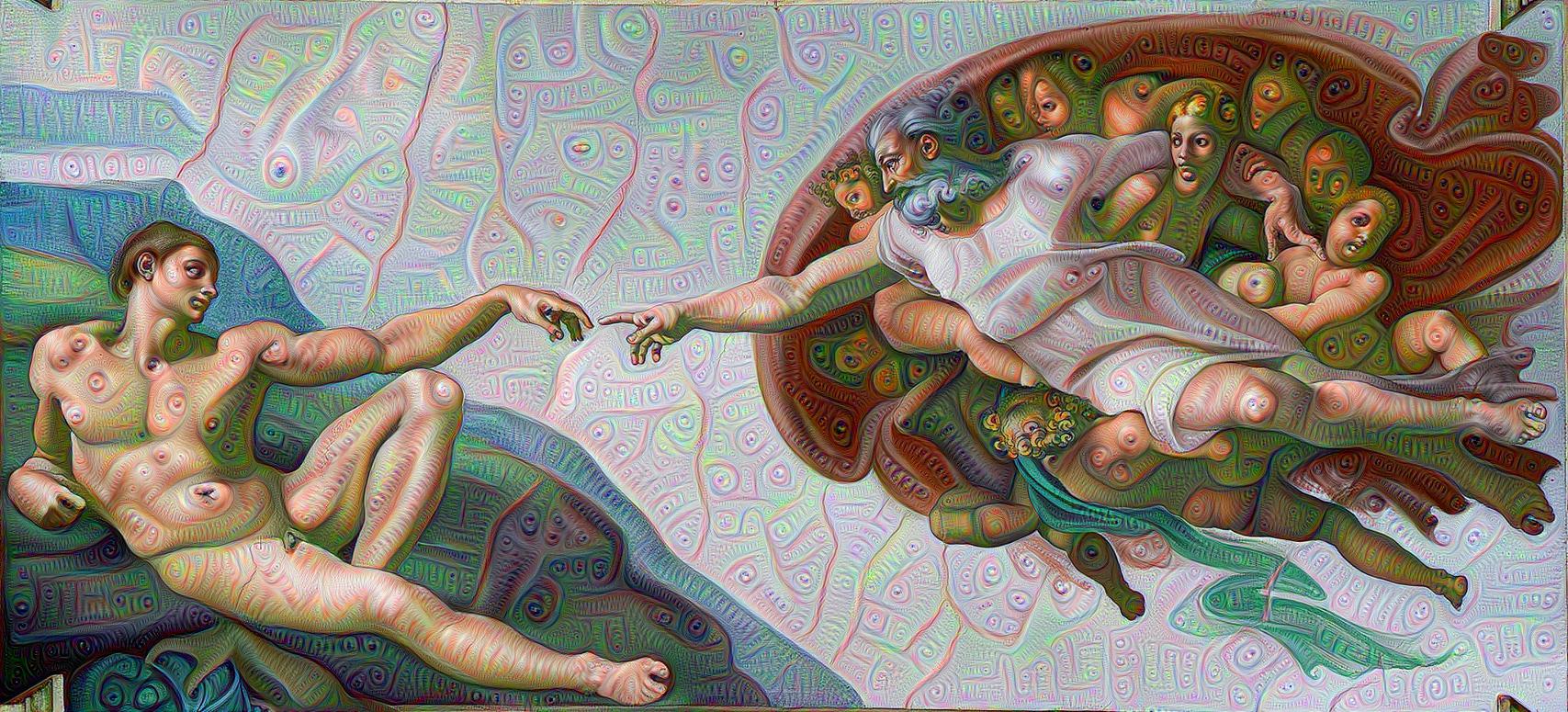

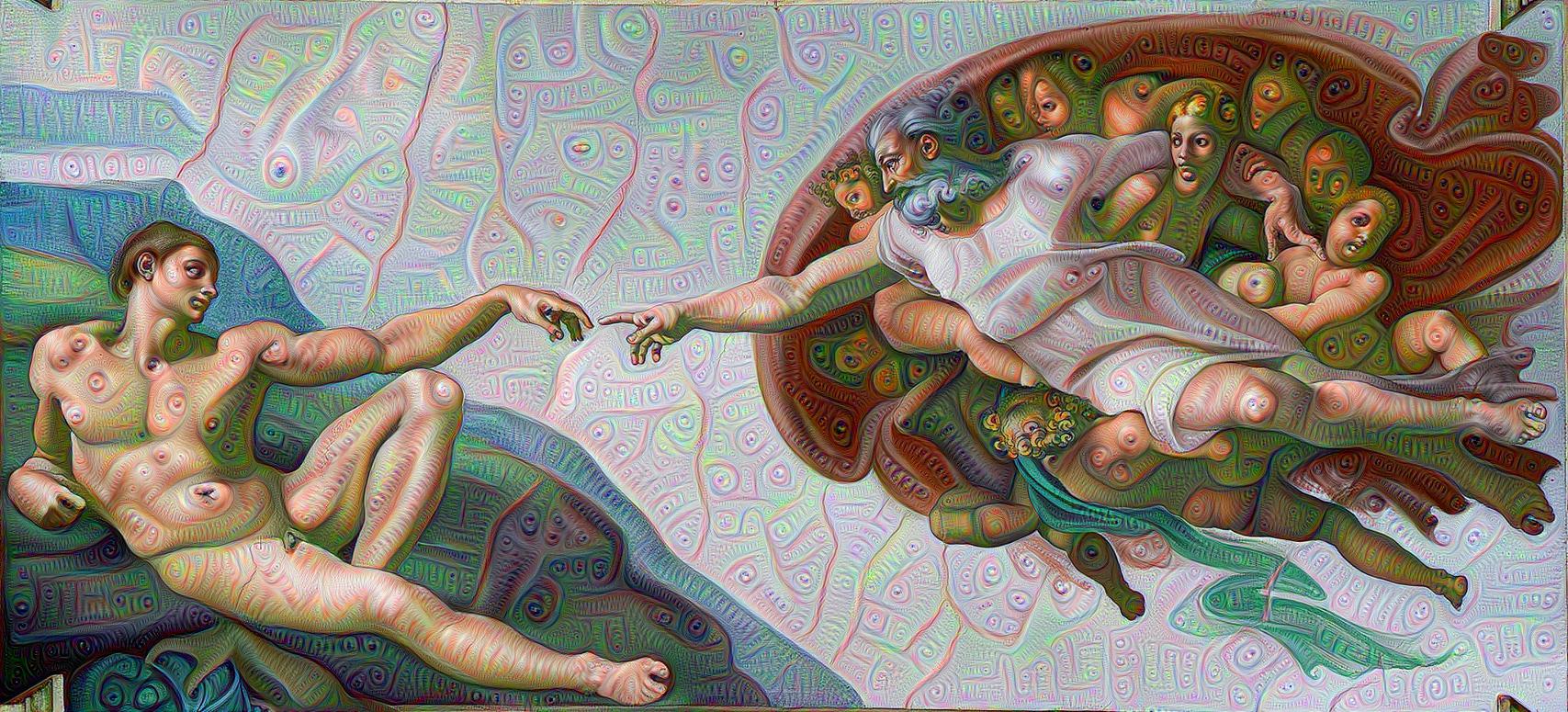

These painting projects, a subset of artificial intelligence research called style transfer, has been extremely successful in replicating and applying the techniques of famous artists. In research by the Bethge Lab in Germany, researchers were able to apply the styles of Picasso, Van Gogh, Wassily Kandinsky, and Edvard Munch to digital images.

To do this, they use object recognition algorithms to ignore the objects depicted in the painting, and focus instead on how the objects are depicted. By doing this, they’re able to divorce content from style, and more accurately study each.

But some would argue that this is merely an aggregate of pre-made human creativity, not something entirely new.

Futurist Jaron Lanier, who leads a research team at Microsoft and first coined the term “virtual reality,” says that he doesn’t think machines could ever be creative.

“The way A.I. works is by recycling data from people,” Lanier told Popular Science. “It ultimately still comes from people, and the problem from that is that the people are made anonymous. We’ve removed ourselves from the equation.”

Artificial intelligence researcher, creator of the site Creative AI and host of the Ethical Machines podcast Samim Winiger says that creativity is a way of operating, not a spark or inherited talent.

“It’s about creative processes, it’s a way of doing things. You learn to be creative; you learn to play guitar.” Winiger said. “From this perspective it becomes demystified, and you can start to use these tools to optimize your own process.”

Winiger sees these tools as a way to augment human creativity, instead of replace it.

In his scenario, a clothing store would be able to generate a dress based on user preferences, and then fabricate it on the spot.

“At that point you can imagine something where an H&M looks very differently,” Winiger said.

And we’re actually getting closer to that reality– this year, IBM’s Watson helped fashion firm Marchesa design a dress for the Met Gala, suggesting directions for colors and materials.

During the production process, Marchesa gave Watson five emotions to draw from: joy, passion, excitement, encouragement and curiosity. Watson analyzed previous dresses from Marchesa, and through its tool that connects colors with emotions, designed a color palate for the garment. Watson services then were able to narrow 40,000 fabrics down to 150 choices, and provide 35 recommendations for designers.

Project Magenta aims to create truly generative music and art, writes Eck. The idea is to start with nothing but the machine, and with the click of a button suddenly have a piece of music with all the elements that a human composer would incorporate.

Magenta will also work on bringing narrative arcs into the generated music through recurring themes and characteristics of the music.

The entire operation will be open to the public, and the alpha release is available on Magenta’s GitHub page today.