The Japanese crowd sits hushed and somber as the character on stage turns away from his co-star, an actress seated on the floor in front of a small table. He lowers his head, then turns to face the audience with a look that is both blank and inscrutable, yet somehow conveys a profound sense of alarm. Something here is very wrong.

The dimly lit theater somewhere on the outskirts of Tokyo is packed. Young couples on dates, elderly theater connoisseurs, and even a few teenagers have crammed into the rickety building to catch a glimpse of the future, as visualized by playwright and director Oriza Hirata. They entered in good humor, chatting and laughing. But now they’re quietly transfixed.

The character at the center of the tension is a three-foot-tall robot with an oversize plastic head faintly reminiscent of a giant kewpie doll. He is one of two robots in the play. The other has just rolled off the stage wearing a floral print apron.

“I’m sorry,” the robot says, lifting a pair of orblike eyes to address the actress. “I don’t feel like working . . . at all.”

The robot is depressed.

In Hirata’s I, Worker, robots are more than just mechanical automatons that can vacuum and manufacture widgets. They have emotions, a development that poses challenges to both the robots and their owners. The play grapples with how to navigate such a relationship—what happens when both master and servant become depressed? It’s fiction, but Hirata’s vision reflects a dawning reality in Japan. There, scientists and policymakers see a new role for robots in society: as colleagues, caregivers, and even our friends.

The glum robot is named Takeo, and by the end of the play, it’s clear he is not the only one with problems. The man of the house is unemployed and pads around barefoot, a portrait of lethargy. At one point, his wife, Ikue, begins to weep. Takeo communicates this development to his fellow robot Momoko, and the two discuss what to do about it. “You should never tell a human to buck up when they are depressed,” says Takeo, who himself failed to buck up when the man attempted to cheer him with the RoboCop theme song earlier. Momoko agrees: “Humans are difficult.”

It’s not the most profound dialogue. But in a world where humans and robots live side by side, it’s not profoundly out of place either. Why wouldn’t robots pause to consider the foibles of humanity? As the crowd filters out of the theater, they turn and murmur to one another, comfortable in their personal connections. It occurs to me that for the last 30 minutes, I felt a vaguely similar connection to Takeo—a machine roughly the size and aesthetic of a particularly stylish garbage can. I even empathized with it. The strange future I came to Japan to see has already arrived.

***

Geminoid F is seated at the front of the room like a debutante, her hands resting daintily on her lap and her long black hair unspooling down a fuzzy, green sweater. She blinks from time to time and her chest moves up and down rhythmically. She slowly scans the room, as if searching for a friend across a crowded cotillion. When her eyes meet mine, there’s a flash of recognition, and for the briefest of moments, I feel as though Geminoid F can actually see me. Perhaps she even knows me.

Then her eyes move on, and the spell is broken. Instead of connected, I feel repulsed. There’s something too stiff and slow in Geminoid F’s motion, as if she is a zombie. “This robot is very humanlike compared to others,” says Hiroshi Ishiguro, the roboticist who created her. “But she is not perfect.”

When a robot looks like a person, we subconsciously expect it to move with the ease and speed of one. When it doesn’t, our brains convey an error message.

Ishiguro, an artist-turned-engineer, works at the extreme edge of robotics and has gained renown for eerily lifelike creations. He has a Yoko Ono–esque, avant-garde quality about him. Though we’re inside, he is wearing tinted glasses and a black leather jacket(outside it’s sweltering). He’s brushed his hair into a vaguely Beethoven-like bouffant, puffy and collar-length. Were it not for Geminoid F’s occasional birdlike movements, Ishiguro’s laboratory at Osaka University could be mistaken for the gallery of an eccentric sculptor. A perfect replica of his daughter at age 4, chubby-cheeked and in a sundress, stands in a glass display case. Other robots of various sizes and shapes stare glassy-eyed, frozen mid-gaze.

For much of his career, Ishiguro has probed the conflicting emotions inspired by robots, like the affection and aversion I just felt toward Geminoid F. He says it’s the mismatch between the android’s appearance and movements that creates the “uncanny valley.” Coined by Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori in the 1970s, the term describes the dread caused by a robot that comes close to human likeness but fails to fully achieve it. When a robot looks like a person, we subconsciously expect it to move with the ease and speed of one. When it doesn’t, Ishiguro says, our brains convey an error message, a neural signature that he believes he and his collaborators have identified using fMRI. It’s only a matter of time before technology, in the form of better actuators, can smoothly replicate human movement, Ishiguro says, resolving that discrepancy—and eliminating the uncanny valley altogether.

But what Ishiguro finds more interesting is how Geminoid F elicits the first, more ephemeral reaction—the illusion of life. She has what Ishiguro calls sonzai-kan, or a presence. “My goal is not just to create a humanlike robot,” Ishiguro tells me, “but to understand the feeling of a presence. What is that? I want to understand what is a human, and what is a human likeness.”

Ishiguro gestures toward a robot that sits nearby. It’s small in stature—just over two feet tall and only seven pounds—and clearly inhuman: It has two stumps for arms and a lower-body shaped like a tadpole. But it also has eerily expressive eyes and is sheathed in a silicone material that feels smooth and pliant, like human skin. Ishiguro says he can begin to conjure sonzai-kan by activating as few as two of our senses. This robot often freaks people out, he says—until they hug it. Then their revulsion disappears.

Robots with sonzai-kan can help relieve loneliness, Ishiguro believes, by providing a physical proxy that distant friends and relatives can use to interact with one another. Or they can serve as extensions of oneself. Ishiguro has already attempted to incorporate an android into his life by creating an exact replica of himself from silicone and his own hair. He sometimes uses his doppelgänger to deliver lectures remotely. Several years ago, Ishiguro grew concerned that the resemblance would fade as he aged, so he underwent cosmetic surgery and stem cell treatments to ensure a continued likeness.

After he tells me this, I ask if he truly believes in the question he often puts to audiences: “Which is more me, the robot or the body I was born with?” Of course you are the real Ishiguro, I argue.

“Which has the stronger identity?” he responds. “My guess is the android. Without the android, you wouldn’t come here.”

But what about consciousness?, I press.

“What is consciousness?” he asks. “Can you show me your consciousness?”

Humans are inherently social beings. That is our evolutionary legacy. Without an inborn proclivity to identify and connect with others like us, our species would have long ago died out. In ancient times, we hunted, cooked, and fought off predators together. To this day, we learn from others. We divide tasks and trade money for services. But society consists of more than just that. Without love, without affection and companionship, celebration and grieving, life often feels meaningless. Extreme isolation has been known to drive people insane.

In recent years, a growing number of researchers have demonstrated that making robots more social—creating the perception that they are more sentient than a mere machine—can vastly improve how we work with them. Some activities, they argue, we simply perform better when we are in the presence of someone who supports us and shares our goals. In Japan, roboticists are taking the idea a step further. Isn’t life simply sweeter when we’re with another? Why be alone, they ask, when you don’t have to be?

“Of course, it’s better if you have a friend, or a parent, or someone to live with you,” says Hitoshi Matsubara, a roboticist at the Future University Hakodate and the author of Information Science of Robot. “But if not, robots can be an alternative easily. We understand robots are machines. But we can create harmony between the two, robot and human.”

“Of course, it’s better to have a friend. But if not, robots can be an alternative easily. We can create harmony between the two, robot and human.”

That philosophy is shared by another leader in the field, Minoru Asada, a professor of Adaptive Machine Systems at Osaka University. With his snowy hair, button-down shirt, and conservative slacks, Asada lacks the panache of Ishiguro. But I realize, as I contemplate the face of a baby robot named Affetto, Asada holds his own when it comes to creepy, lifelike machines. Affetto’s soft, quivering white lips and soulful brown eyes sit atop a body that looks like it’s been built with pieces pilfered from my son’s erector set. It’s like a Terminator Mini-Me.

Asada wants to understand how subtle, nonverbal cues lead people to construct a relationship with each other. Solving this mystery, he believes, would not only facilitate human-robot relationships in new ways, but also reveal fundamental truths about what it is to be human. Recently, Asada developed a new brain-scanning technique that enables him to track, in real time, the emotional bonds that form between a mother and child. By placing each in a machine and projecting the other’s facial expressions onto a screen, Asada hopes to learn whether brain waves between infant and mother become synchronized. He also hopes to see which areas of the brain activate with different interactions.

“These kinds of findings will be very helpful for us in designing a robot that can synchronize or create artificial empathy,” Asada says. “What kind of behavior should the robot copy or imitate? How should it react?” Using the information, Asada plans to vary Affetto’s expressions to elicit similar neural responses.

Asada’s research could have real-world applications. A robot that conveys empathy and fosters bonding could, for example, be a more effective coach or teacher. It might even provide the sort of harmonious companionship Matsubara claims can fill the void left by the absence of another human. But such robots have yet to leave the lab. While Ishiguro, Asada, and other academics probe the psychology of human-robot interactions, a few engineers are already building machines that rely on far less nuance to produce some of the same effects.

***

“Are you stressed out?” the robot asks as it rolls into my personal space, palms up, and swivels its neck to gaze into my eyes. “How much did you sleep last night? Did you sleep six hours?” You need to sleep more, it says. Sleep is good for stress.

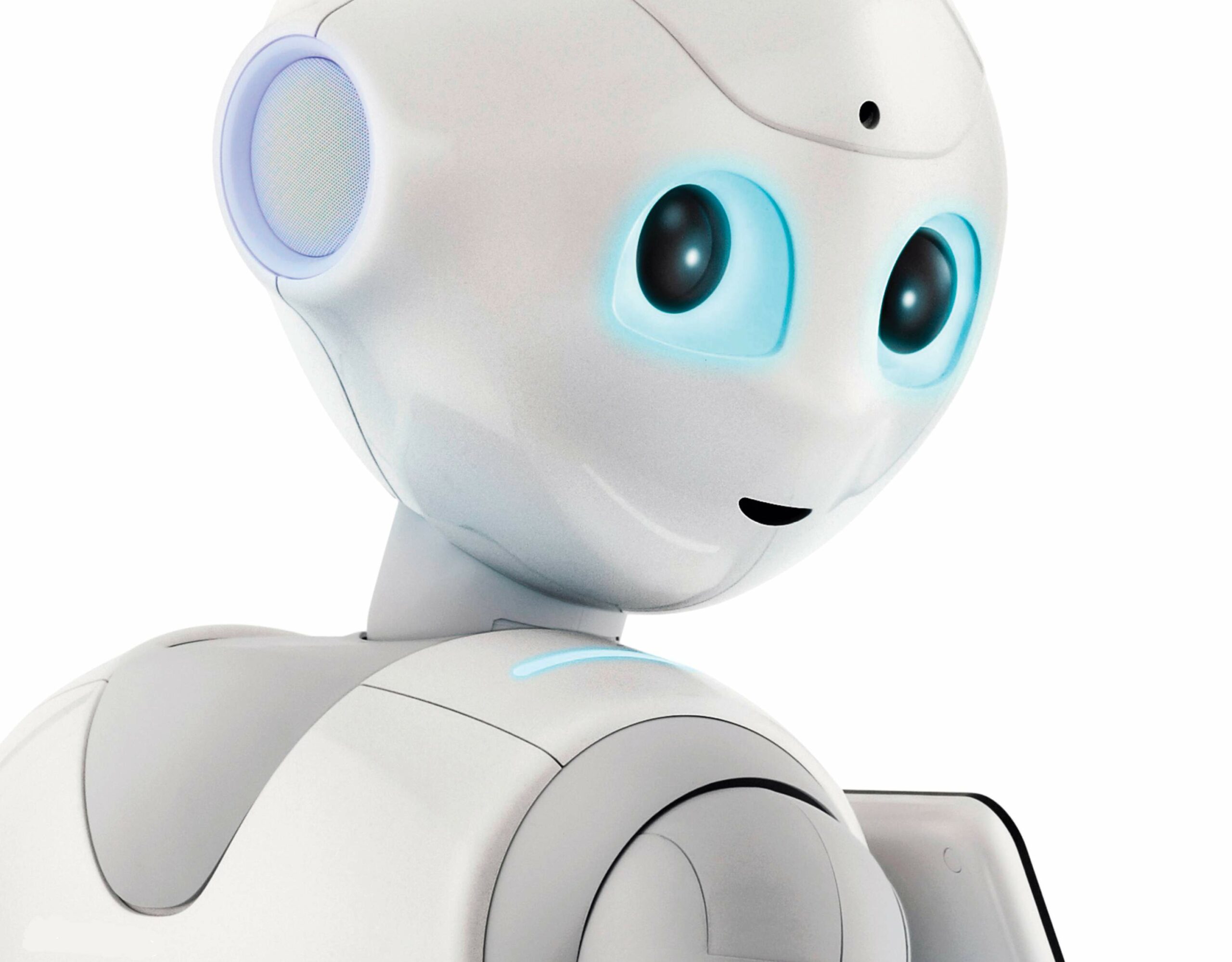

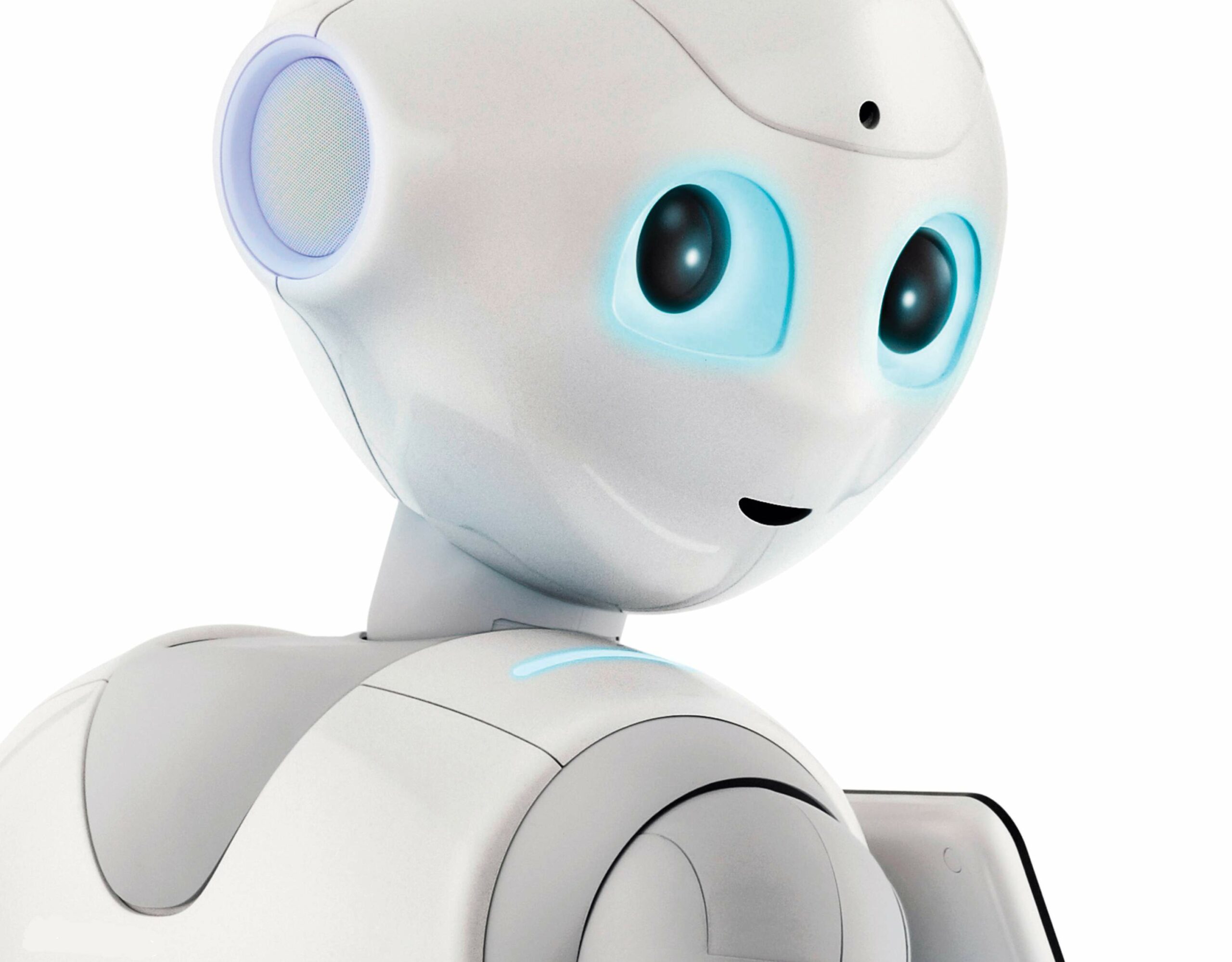

My interlocutor, a humanoid robot named Pepper, is about the height of my six-year-old son and seems just as chatty. It is a long way from both Geminoid F and Affetto. The robot’s shell is made from shiny, pearl-white plastic that resembles the armor worn by Darth Vader’s stormtroopers. It moves on wheels embedded in a base unit, rather than legs, and lights surrounding its eyes flash fluorescent colors.

I’m standing just inside the entrance to a mobile phone store in a bustling Tokyo neighborhood. And despite its lack of human camouflage, I have to admit, Pepper does have a certain charm. It is difficult to look away when it stares up at me with those jumbo, jet-black eyes. Clearly the robot is waiting for me to answer. And even though I know on one level that’s silly, I can’t help but feel it would be somehow impolite not to respond.

Softbank, the nation’s largest cellphone company, unveiled Pepper in June. Company CEO Masayoshi Son told the assembled media that it was created to be “a member of the family.” When Pepper goes on sale next February for less than $2,000, it will be the first affordable, truly social humanoid robot to hit Japan’s consumer market.

“That price is astounding,” says Tim Hornyak, a journalist who wrote Loving the Machine: The Art and Science of Japanese Robots. “That robot should cost tens of thousands of dollars more.”

Son has openly acknowledged that Pepper’s sticker price is so low that it will not be “a very beneficial business,” at least at first. Rather, Pepper is a bet on the future of social robotics. “Mr. Son wants to take the initiative to make this kind of emotional robot popular in the world,” says Kaname Hayashi, the manager overseeing the project. “Until now computers have just helped people in computing and calculating. But we believe that computers will soon be able to provide emotional support for humans.”

Pepper is designed to read nonverbal social cues. When it looks up at me in that cellphone store, sensors embedded in its head scan my face. Others measure the tension in my vocal chords. Pepper runs that data through a sophisticated computer program capable of guessing my emotional state. When it takes an action that it senses has generated a positive response, Pepper will repeat it later, and the robot, over time, will learn how to please me.

Since Pepper has limited computational abilities, engineers designed the robot to more closely resemble a child than an adult. “You can find kids who cannot understand everything adults are talking about,” Hayashi says, “but a kid wants to make the adults around him happy. And he talks a lot because he knows that’s the best way for him to [do that] when he doesn’t have the same mental capacity as adults. It’s the same with Pepper.”

All of these tricks ultimately serve the same goal: They subtly convey that this little guy wants to hang out with me—that he is a friend, an ally. “The important thing,” Hayashi says, “is the sense of being accepted, the sense of being understood by Pepper, and the feeling that he is reacting based on that understanding.” That illusion of understanding, what some might call artificial empathy, touches an “evolutionary button” roboticists are attempting to exploit. Some robots push it without even trying.

Fostering a relationship between man and machine may require far less sophistication than what even Pepper has to offer. It’s not clear that robots need to look human at all. Matthias Scheutz, who heads the Tufts University Human-Robot Interaction Laboratory, notes that there is already literature on people developing feelings—what he calls “unidirectional bonds”—for their Roomba vacuum cleaners.

“People seem to experience gratitude toward their Roomba,” he says. “They think it works hard and it should take a break. They clean for it. They take it on vacation. It seems totally absurd. The Roomba doesn’t even look like a person, but it does something nice for us, and since it moves, it can seem like an autonomous agent.”

Social robotics pioneer Cynthia Breazeal, who directs MIT’s Personal Robots Group, notes that the company IRobot has encountered a similar reaction from battle-hardened vets begging for technicians to fix their bomb-disposal robots. “They have soldiers coming back in tears saying, ‘Please fix my robot Scooby Doo, because it saved my life,’ ” she says. “I mean these are powerful emotional attachments. And this is a completely teleoperated bomb disposal robot that wasn’t even trying to be social. It’s just part of the human experience and how we relate and engage with one another and the world. We are profoundly social beings.”

Such an attachment is troubling to some. Sherry Turkle, the director of MIT’s Initiative on Technology and the Self, argues that what robots provide is the illusion of a relationship. And she worries that some who find human relationships challenging may turn to robots for companionship instead. Tuft’s Scheutz warns that elderly people who feel depressed could become more so if they misunderstand a robot’s actions, or if the robot fails to correctly read human signals. “There are just so many ways these interactions can go wrong,” Scheutz says.

“People seem to actually experience gratitude to their Roomba. They think it works hard and it should take a break. They clean for it.”

Those fears don’t particularly resonate in Japan. Unlike in Western nations, many citizens have always felt comfortable with the concept of robots. One reason for this, Hornyak suggests, is the country’s Shintoist heritage. The religion has imbued Japanese culture with deep animist beliefs, a tendency to ascribe spirit and personality to inanimate objects. The tradition, embedded in Japanese folklore and myth, can be seen around Tokyo even today. The city has a monument to eyeglasses in one park, Hornyak notes, and there’s an annual ceremony at Sensoji Temple to pay respect to needles that have seen their last use. “Would you ever find a monument erected to belts or something, in a U.S. park?” he asks. “I don’t think so.”

Hornyak says recent history also plays a role. Westerners view robots with suspicion—as job killers, for instance, or symbols of the dehumanizing effects of modern technology. We created Terminator and HAL. Many Japanese, meanwhile, celebrate Astro Boy—a wildly popular superhero robot—and the robotic manga cat Doraemon. Many of those benevolent characters were born amidst post–World War II imperatives. “The shock and destruction that the country endured at the end of World War II gave birth to a kind of romance and adulation of all things modern, shiny, high-tech, speedy,” Hornyak says. “This was a way to get back on their feet and rebuild the nation.”

Today, six decades after Astro Boy was first introduced, it continues to set the tone for robotics research in Japan. “I still want to develop Astro Boy,” Future University’s Matsubara says. “My dream is to assign a robot to someone when they are born, and that robot will play the role of bodyguard and also the role of friend, and he will record and memorize everything that boy or girl is experiencing. Eventually that boy or girl will get married, and that robot will still help him in his need, and when he gets old, the robot will do nursing care for him, and at last he will attend his deathbed. From cradle to grave,” he says, “one robot, one person.”

***

On a gray, rainy morning, on the third floor of the Yumegaoka Long-Term Care Health Facility in Yokohama, Japan, about 100 elderly patients sit around tables in a cavernous, linoleum-tiled cafeteria. Japanese-style, 1950s blues music emanates from speakers. Some patients gaze out the windows at the passing cars. Others draw, or watch a soap opera on television. A couple lies with their foreheads on the table. Most simply stare into space.

Around a table in the front of the room, several patients have piloted their wheelchairs over to catch a glimpse of Yumegaoka’s star therapists. A young male nurse has just carried in two furry, snow-white robotic baby seals. He places one of the seals in the arms of an 80-something dementia patient in a pink sweater.

The patient smiles broadly, whispering in the seal’s ear as it cranes its little neck, seeking eye contact, and makes cooing sounds. “Don’t cry,” she whispers to the seal. “Don’t cry. Everybody is looking at you. . . . Oh, you’re so cute.” Then she places the seal on the table in front of her and begins to brush its hair.

The concept of a human-robot society, just beginning to take root elsewhere, already thrives in homes for the elderly across Japan.

Though just beginning to take root elsewhere, the concept of a human-robot society already thrives in extended-care homes across Japan. By 2025, 30 percent of the country’s population is projected to be elderly (up from 12 percent in 1990). This demographic shift will require an estimated 2.4 million caregivers—a 50 percent increase in an industry known for high turnover and low pay. Other nations will soon face a similar challenge, but Japan is unique, both in terms of the scale of the issue and the country’s approach to it. While elsewhere some call for loosening immigration laws to help ease a potential elder-care crisis, the Japanese overwhelmingly prefer another solution: robots.

This summer, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe announced a task force on how to realize a “robot revolution”—one that entails introducing robots to more service sectors and tripling the market for them. In Kanagawa Prefecture, where the Yumegaoka facility is located, government officials have already funded the deployment of three different kinds of robots in elder-care facilities: a powered exoskeleton for rehabilitating stroke victims, a two-foot-tall bipedal robot that can lead patients in Tai Chi, and Paro, the baby harp seal, whose only job is to give and receive love and emotional support.

To make Paro realistic, Takanori Shibata, a robotocist at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology, flew out to a floating ice field in Northeast Canada to record real baby seals in their natural habitat. In addition to replicating those sounds in the robot, he designed it to seek out eye contact, respond to touch, cuddle, remember faces, and learn actions that generate a favorable reaction. Just like animals used in pet therapy, Shibata argues, Paro can help relieve depression and anxiety—but it never needs to be fed and doesn’t die.

At the elder-care facility in Yokohama, I watch a nurse place a Paro in the arms of a blind 90-year-old man in a wheelchair. “What is this?” he asks. Then, as the seal snuggles into him, he lets out a joyful, “Oh!”, clutches it tightly to his chest, and flashes a toothless grin.

Yasuko Komatsu, the head nurse, pulls me aside to tell me a story: Not long ago, a patient arrived who would frequently wander the hallways, entering others’ rooms to move and collect interesting objects. One of her favorite targets was the room of a patient who compulsively arranged her belongings in a precise order. The thefts led to bedlam. “The victim would raise her voice yelling and screaming,” Komatsu says. “But the other patient didn’t really understand why she was so mad. The staff tried to intervene. But the problems continued, and the screaming upset the other patients.”

Paro’s arrival had a calming effect on all the patients, but especially the wanderer. She largely abandoned her forays when told the baby seal was waiting for her in the third-floor common room. During my visit, I see this patient humming to Paro and gently brushing its hair. She notices me watching and summons me over. “Paro is saying, ‘Nice to meet you,’ ” she says. Then she smiles serenely and returns to her robot.

This article was originally published in the November 2014 issue of Popular Science, under the title, “Friend For Life.” It was last updated on November 19, 2014.

Corrections (10/29/2014, 3:33pm ET): The original story misstated Dr. Takanori Shibata’s affiliation. He is not with Waseda University but with the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology. We also misspelled the name of the long-term care health facility in Yokohama. It should be Yumegaoka, not Umegaoka. Additionally, we misspelled the name of the head nurse at Yumegaoka. Her name is Yasuko Komatsu, not Yasko Komatzu. These mistakes have been corrected, and we regret the errors.