Between lockdowns, missing milestone events such as prom or graduation, and general worry over the state of the world in the past few years, times have been particularly tough on adolescents.

Reports of anxiety and depression in adults increased by more than 25 percent in 2020, and some new research suggests that mental health and the neurological effects of the pandemic on adolescents could be even worse than in their adult counterparts.

[Related: Neuroscientists are mapping all 100 billion cells in the human brain.]

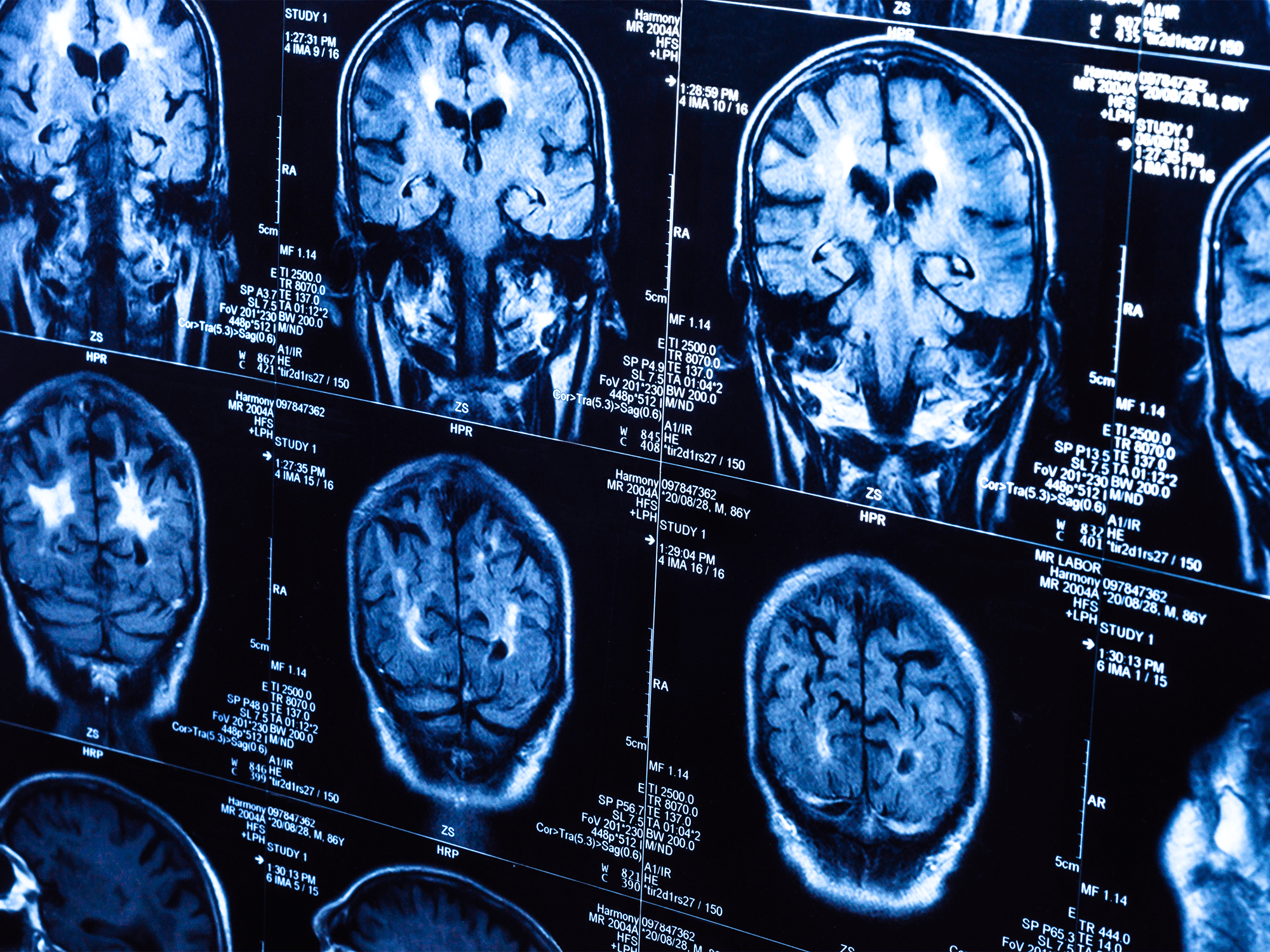

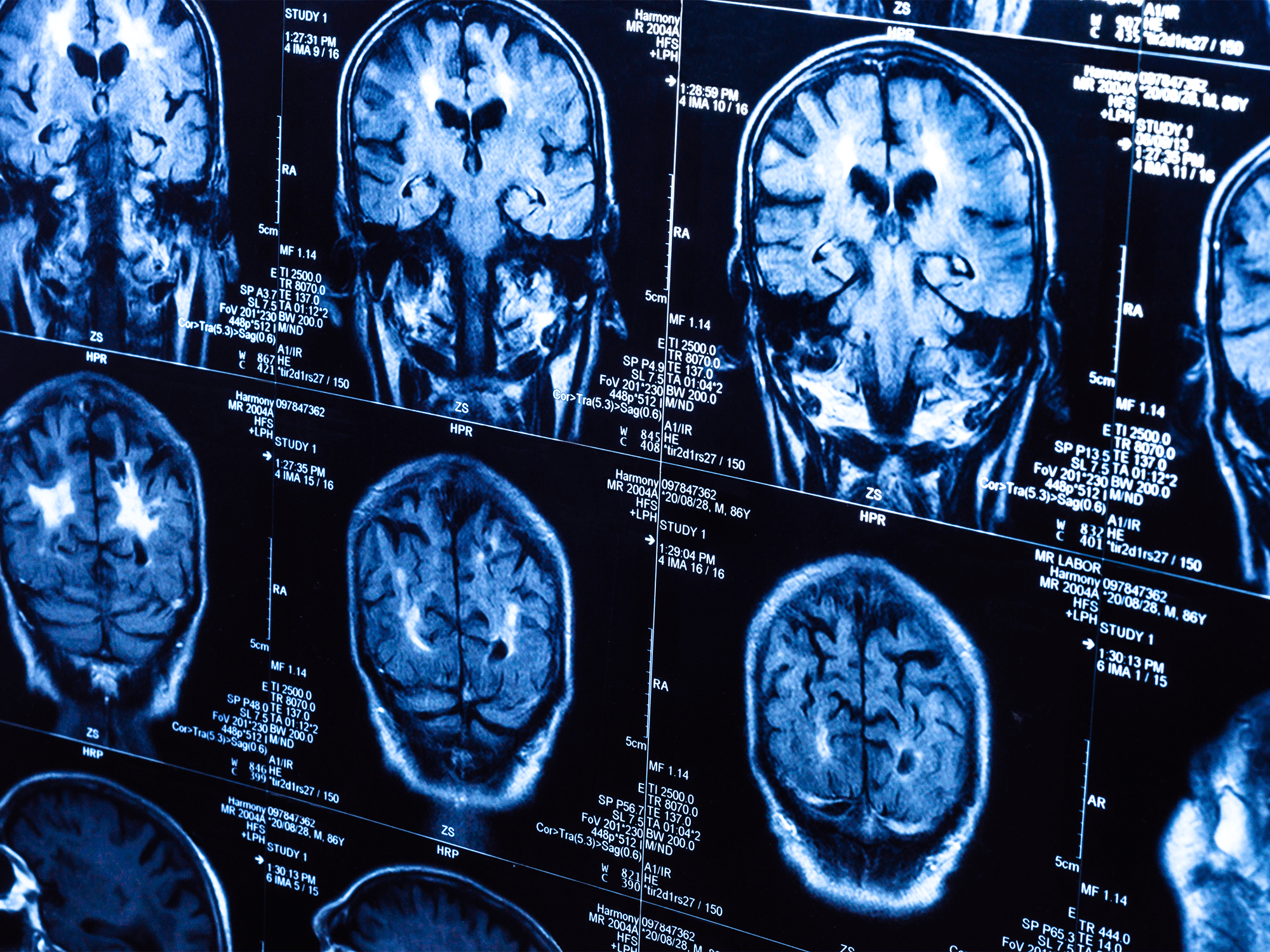

Scientists are beginning to look at how the past two and a half years of pandemic life is affecting the brains of teens. A new study published today in the journal Biological Psychiatry: Global Open Science, suggests that stressors related to the COVID-19 pandemic have physically changed teen brains, causing their brain structures to appear multiple years older than the brains of comparable peers before the pandemic.

“We already know from global research that the pandemic has adversely affected mental health in youth, but we didn’t know what, if anything, it was doing physically to their brains,” said Ian Gotlib, study author and psychology professor at Stanford University’s School of Humanities & Sciences, in a statement.

Changes in brain structure occur naturally as we age. During early teenage years and in puberty, the hippocampus (which controls access to certain memories) and the amygdala (which helps moderate emotions), go through growth spurts like the rest of the body. The tissues in the cortex, which controls executive functioning, becomes thinner at the same time.

To get a closer look, Gotlib and his team compared the MRI scans of 163 children that were taken before and during the pandemic. The study showed that during the COVID-19 lockdowns, this developmental process in the brain sped up in adolescents. According to Gotlib, an accelerated change in “brain age” has typically appeared only in children and adolescents who have experienced chronic adversity (family neglect, violence, family dysfunction, etc.). These kinds of early adverse experiences can be linked to worse mental health outcomes later in life.

However, it is still unclear whether the changes in brain structure that this study observed will be linked to changes in mental health later on in life.

“It’s also not clear if the changes are permanent,” said Gotlib. “Will their chronological age eventually catch up to their ‘brain age’? If their brain remains permanently older than their chronological age, it’s unclear what the outcomes will be in the future. For a 70- or 80-year-old, you’d expect some cognitive and memory problems based on changes in the brain, but what does it mean for a 16-year-old if their brains are aging prematurely?”

The results of this study could have implications for some of the longitudinal studies that have spanned the course of the pandemic. Scientists will have to account for abnormal rates of growth in the brain for any research down the road involving this generation, if those who experienced the pandemic generally show this rapid brain change.

“The pandemic is a global phenomenon—there’s no one who hasn’t experienced it,” said Gotlib. “There’s no real control group.”

[Related: We shouldn’t disregard the ideas that come from teens’ developing brains.]

Co-author Jonas Miller, an assistant professor of psychological sciences at the University of Connecticut, added that results like this may have serious consequences for this generation later in life.

“Adolescence is already a period of rapid reorganization in the brain, and it’s already linked to increased rates of mental health problems, depression, and risk-taking behavior,” Miller said. “Now you have this global event that’s happening, where everyone is experiencing some kind of adversity in the form of disruption to their daily routines – so it might be the case that the brains of kids who are 16 or 17 today are not comparable to those of their counterparts just a few years ago.”

Gotlib plans to follow the same cohort of teens from this study through later adolescence and into young adulthood, looking to see if the pandemic changed the trajectory of brain development long term, alongside their mental health. He also plans to compare the brain structures of those who were infected with COVID-19 and those who weren’t infected with the virus, with the goal of identifying any differences in the brain potentially caused by infection.