Sponsored Content

Gear

News, roundups, and reviews of the technology that shapes the way we live.

Latest in Gear

Sponsored Content

Make your old PC feel new with Windows 11 Pro for only $10

Sponsored Content

A full Microsoft Office Suite for under $30? Yes, this is real.

Sponsored Content

Make healthier choices with a tracker ring for under $300

Sponsored Content

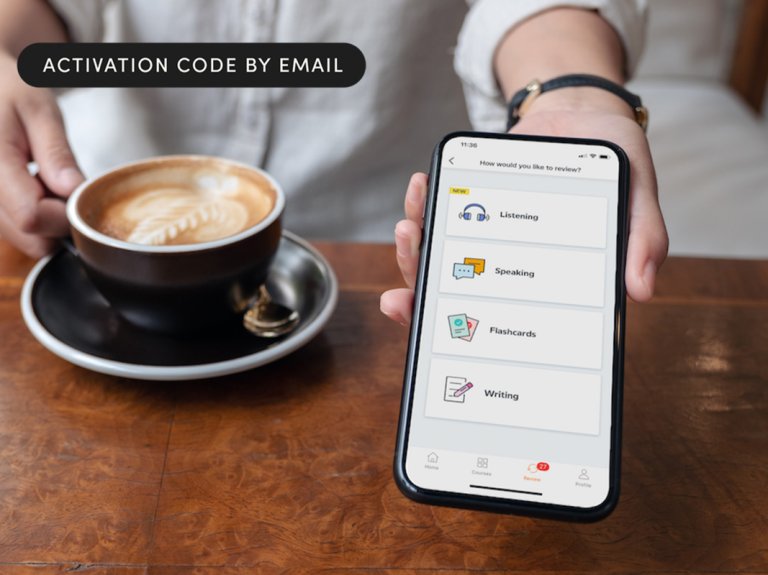

Learn guitar faster with structured, science-backed tools for $110

Sponsored Content

The latest version of Microsoft Office Home is only $120

Sponsored Content

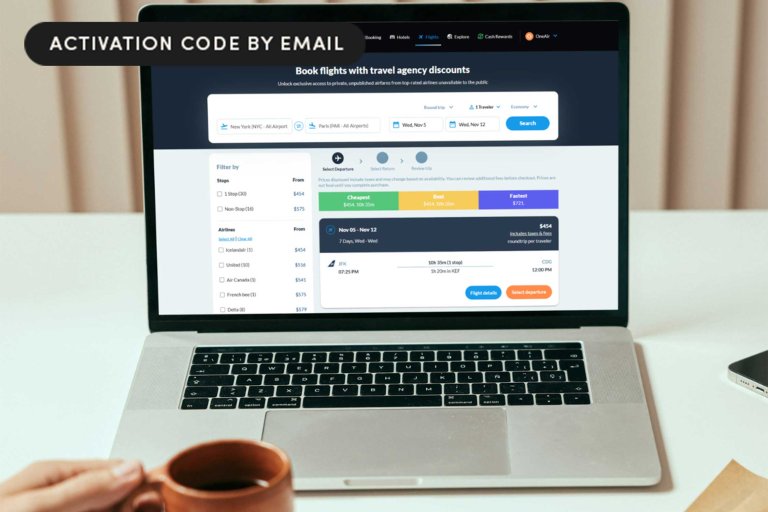

Automate your travel deal hunting with OneAir for just $60

Sponsored Content