This article originally appeared in Nexus Media News. It is part of Covering Climate Now’s ‘Food & Water’ joint coverage week and was made possible by a grant from the Open Society Foundations.

Maritza del Rosario López Cortés comes from a long line of farmers in central Puerto Rico. But it was only after Hurricane Maria devastated the island in 2017, leaving many residents in her hometown of Villalba without electricity or access to food, that she fully appreciated the importance of local growers.

“It took so long for food to get here,” López Cortés said. “There was no fresh food for what felt like ages.” She and her family relied on shelf-stable MREs to supplement their meals—packaged ready-to-eat meals distributed by FEMA—for weeks, she said. She remembers the relief she felt when she discovered plantains and root vegetables that were still good to eat in fields near her home during that time.

The experience showed how vulnerable the island’s food systems are and led the 37-year-old cosmetologist and mother of two to revive her family’s farm. She took the helm at Hacienda López Cortés in 2020, now a 6-person operation, which grows staple crops like calabaza (squash), coffee and plantains. She keeps an active social media presence, posting photos of her harvest and employees to Facebook, and sells most of her products to local restaurants and supermarkets. She was excited to discuss some of the traditional farming practices she employs, which include using bulls to plow the fields.

“I ask people all the time, if the supermarkets close, if the stores close, what would you eat—do you know where it’s coming from?” López Cortés said. “Seeing how much people need access to fresh food motivates me every day.”

In the five years since Hurricane Maria, Puerto Rico has seen a resurgence in small-scale farming and projects that educate locals about where their food comes from. Many, like López Cortés’, have learned to rely heavily on regenerative growing practices, like crop rotation and using shading plants.

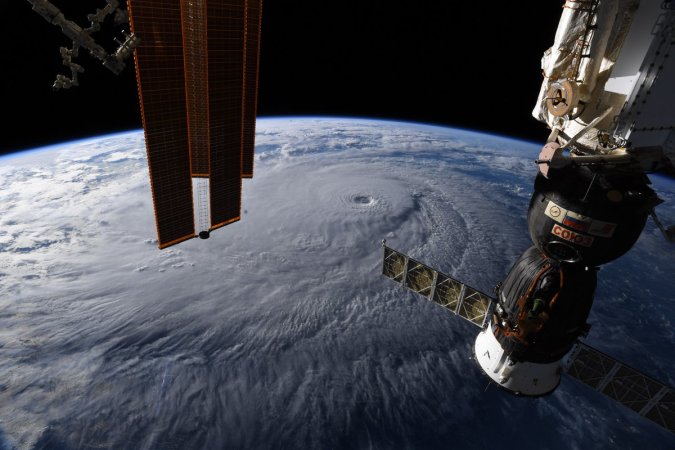

The US territory is vulnerable to a number of natural disasters, including intense tropical storms and drought. Hurricane seasons, made longer and more intense by climate change, have left behind a fragile electric grid that causes regular power outages, disrupting daily life, work and education for Puerto Ricans. More than 80 percent of Puerto Rico’s food is imported, so when a major storm hits, it can delay shipments from the mainland. Residents are left with half-empty shelves at the store.

Rising costs of living on the island combined with higher food prices worldwide will only make it more difficult for Puerto Rican families to prepare for future natural disasters, said Luis Alexis Rodríguez-Cruz, a food systems researcher at the USDA’s Caribbean Climate Hub. A 2020 report from George Washington University found that about 40 percent of Puerto Rican families reported being food insecure in recent years. Survey participants revealed that they often ran out of money for food and that they went hungry. Food prices in Puerto Rico are about 18 percent higher than they would be on the mainland, according to the island’s Institute of Statistics.

Supporting local farmers can improve food security across the island, Rodríguez-Cruz said. What’s more, devastating events like Hurricane Maria present opportunities for farmers to build more resilient systems, according to a study he co-authored last year. Rodríguez-Cruz and his fellow researchers found that farmers “who faced a total loss adopted the most adaptation practices.” (The study also found that farmers with higher education levels were more likely to adopt adaptation practices.)

Rodríguez-Cruz said he has noticed a growing interest in local agriculture and supporting Puerto Rican farms. “[You hear it] on the radio and the TV. There’s more conversation around food production, agriculture. And I think that’s definitely what happened with Maria. [The storm] catalyzed much of that,” he said.

He pointed to operations like El Josco Bravo, an organic teaching farm about 20 miles west of San Juan, which has churned out a new generation of organic farmers.

“FEMA gave my mother a bag of Skittles. My mother’s diabetic.”

Ruth Santiago, Puerto Rican lawyer

Puerto Rican TikToker and independent journalist Bianca Graulau posted a video about El Josco Bravo’s educational program a few months ago. She reported that the program had resources for about 150 participants, but received many hundred more applications. (Representatives from El Josco Bravo could not be reached for comment.)

Though nongovernmental programs have stepped up to provide technical education and support, Rodríguez-Cruz said the local and federal government could do more to help small farmers with administrative and bureaucratic challenges that come along with running a farm, Rodríguez-Cruz said. That might include streamlining paperwork and helping new farmers navigate guidelines and regulations, he said.

Supporting local food systems can improve public health outcomes during and after natural disasters, said Ruth Santiago, a Puerto Rican lawyer and activist. “After Hurricane Maria, FEMA brought in food and it was horrible—very highly processed with high sugar content,” she said. “They gave my mother a bag of Skittles. My mother’s diabetic.” (Around 16 percent of adults on the island have diabetes, compared to 10 percent of adults on the mainland.)

Santiago, who advocates for rooftop solar electricity with a group called Queremos Sol, said local farming, like renewable energy, could make the island more climate-resilient. “We really need to think about alternate ways of having food security and sovereignty here in order not just to be resilient, but also to cut down on medical expenses, which are very high here.”

The island’s ongoing power outages exacerbate food insecurity by making it difficult to refrigerate perishables. In April, a fire at a power plant shut off power for more than one million customers in Puerto Rico. San Juan residents protested outside of the island’s power authority’s offices, with some placing bags of spoiled food to show authorities what the outages had cost them.

López Cortés has found meaning in her new calling as a farmer, but it’s also helped her household’s bottom line. “I don’t do those huge $500 to $600 grocery hauls anymore,” she said. “I buy some meat, fish and rice, but my roots and vegetables come from my field. I don’t buy canned or frozen food as often anymore.”

As Puerto Rico heads into another hurricane season, she said she feels better prepared than she was for Maria. “If another big hurricane comes, I think I’ll be able to put food on the table for my family,” she said. “Not just my nuclear family, but my extended family—my brothers, my uncles, too.”

She paused.

“My goal is that my produce ends up on the plate of other Villalba residents. Once everyone here has a full belly, I hope [my food] ends up reaching the rest of Puerto Rico,” López Cortés said.