In Colombia in 2013, a man showed up to a hospital with a confusing array of symptoms. He was gaunt, having lost a lot of weight in the past few months. He was HIV-positive and hadn’t been taking his medication. He was fatigued, with a fever and a cough. Stool samples revealed that he was carrying the parasite Hymenolepis nana, a common type of tapeworm; strangely, a scan showed cancer-like nodes in his lungs and lymph nodes.

His doctors weren’t sure how to diagnose the man—the cells looked and behaved like cancer, but they weren’t the man’s own cells. The cancer seemed to be from another multi-celled organism. The disease progressed and 72 hours after he was admitted to the hospital, the man died.

Doctors determined that the man died from his tapeworm’s cancer—the first such case ever reported, according to the study published today in the New England Journal of Medicine. And that’s got some scientists asking questions about how much we know about what causes cancer in the first place.

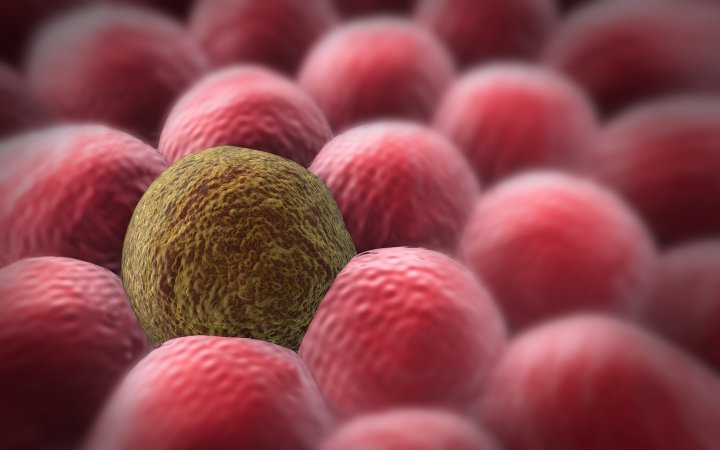

Scientists have known for a while that some infectious agents such as parasites can cause cancer. Two types of parasitic flatworms that live in the liver have been connected with increased incidence of cancer in bile ducts found in the intestines; another called Schistosoma haematobium can be ingested through water and is known to cause bladder cancer. The hypothesis is that these parasites can cause inflammation in the host’s tissues, which causes them to reproduce faster and increase the likelihood of a mutation.

But this case is different—the cancer was in the parasite’s cells, not the man’s. To see what might have caused the tapeworm’s cancer, the researchers compared the genes of the worm’s normal and cancerous cells. The researchers found that several of the genetic mutations in the cancerous cells occurred in the same genes as malignant mutations in human cells.

That not only shows a level of biological commonality, one researcher told NPR, but this case also shows how cancerous cells can spread out of control when the immune system is compromised.

This strange case raises even more questions about possible misdiagnoses of cancer in developing countries, and about the role of the immune system in fighting or protecting the body against cancer. “The host–parasite interaction that we report should stimulate deeper exploration of the relationships between infection and cancer,” the study authors write.

And though the doctors weren’t able to act quickly enough in this case, answering these questions might lead to better cancer treatments in the future.