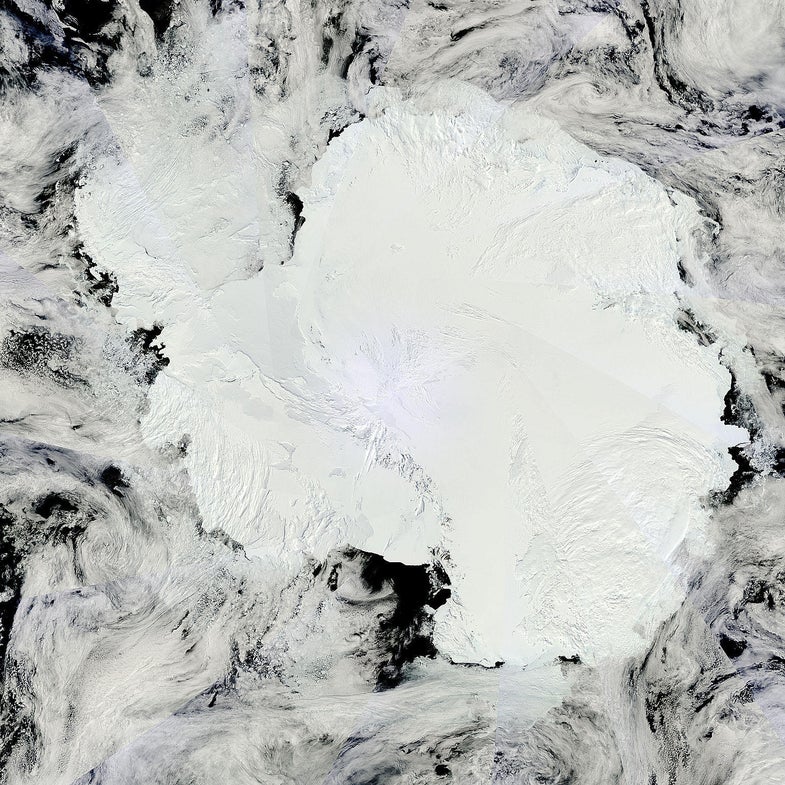

Parts Of Antarctica’s Ice Sheet Seem To Be Growing. No, Global Warming Is Not Over.

Some areas of the continent are gaining ice. What does it mean?

In a paper published in the Journal of Glaciology, scientists from NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center found that between 1992 and 2001, Antarctica gained 112 billion tons of ice a year, and between 2003 and 2008, Antarctica gained 82 billion tons of ice per year.

That finding disagrees with data from NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE), two satellites which recorded Antarctica losing 92 billion tons of ice every year between 2003 and 2014.

So, is it melting? Yes and no. Antarctica is a very large place and while some areas in the West are melting at alarming rates, scientists found that some areas of East Antarctica are gaining ice. One of the most recent studies about the ice gain even caused some headlines to wonder if global warming is over.

Spoiler: it isn’t.

Why the stark disagreement? For one thing, the two studies were looking at different things. The GRACE satellites measure the mass of the ice, while the study from the Journal of Glaciology looked at the volume of the ice over time, inferring the increase in ice mass from the measurements of the elevation of the ice’s surface, correlated with ice cores from the ground.

Both studies found that parts of West Antarctica were losing ice, and parts of East Antarctica were gaining ice, but they differ on how much one offsets the other. But both agree that in the long term, we all need to be paying close attention to the ice loss, which is currently accelerating.

“If the losses of the Antarctic Peninsula and parts of West Antarctica continue to increase at the same rate they’ve been increasing for the last two decades, the losses will catch up with the long-term gain in East Antarctica in 20 or 30 years — I don’t think there will be enough snowfall increase to offset these losses.” Jay Zwally, author of the Journal of Glaciology paper said in a statement.

In fact, a paper published today that shows that if part of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet is destabilized, nothing can be done to stop the entirety of the sheet from melting, potentially raising sea levels by 9 feet (3m) over an unspecified amount of time.

Climate change isn’t something that you see happening day to day. A warm day in February doesn’t herald the end of life as we know it, and a cold day in July doesn’t show that climate change has magically stopped. Climate isn’t as mutable as the weather. It’s a persistant pattern that only changes very gradually, oftentimes so slowly that we don’t even notice when we go about our day to day lives.

That’s where data comes in. Memories can be fuzzy, but recorded measurements help us compensate for our inherent biases. Scientists are gathering as much data as possible from as many sources as possible, trying to gaze into a very uncertain future. It’s like trying to put together a 1,000-piece jigsaw puzzle of clear blue sky with shapeshifting puzzle pieces and a countdown clock ticking in the background. In that situation you need as much help as you can get from as many people as possible. They won’t always agree about which piece goes where, but you need all the pieces on the table before you can get the whole picture.

That’s why it’s to be expected that all the measurements don’t line up perfectly right now. Eventually, we’ll figure out how it fits into the rest of the puzzle. And soon, there will be even more puzzle pieces to add. In 2018, NASA will launch ICESat-2, a satellite that will be able to measure ice sheet elevation changes and sea ice thickness to less than half an inch.