The periodic table of elements, organized thoughtfully from hydrogen to ununoctium, is a tribute to the accomplishments of modern chemistry and physics. Since Dmitri Mendeleev developed an early version of the now-ubiquitous layout in 1869, discovering a new element has been a surefire way for a scientist to grab a place in the history books–and in the pages of Popular Science.

See the gallery.

Showing just how fundamental the elements are to modern science, the third-ever issue of PopSci, from August 1872, included a lengthy essay outlining the history of the “different sorts of matter,” predicting correctly that scientists might continue discovering elements for “centuries to come.”

But it hasn’t all been fame and glory. PopSci announced in 1926 that the first American had identified a new element, only to declare later that “illinium” was a fake. Oh, and there was that time in 1931 when we proudly reported that scientists could pack up and go home: all the elements had been found!

Check out this week’s archive gallery for more super-nerdy chemistry drama.

New Atomic Charts: February, 1950

The “Atomic Era” was barely five years old when PopSci published this article on the new neptunium family of radioactive elements. Already, “atomic-age discoveries… have been happening too fast for the chemistry and physics books to keep up.” The quest to fill the empty slots of the periodic table became an obsession after scientists grasped the awe-inspiring potential of nuclear energy. In 1950, there were 96 known chemical elements (today we have 118.) The U.S. Atomic Energy Commission had just de-classified four charts of the radioactive families of elements, which PopSci painstakingly reproduced as a permanent reference for readers. Up for debate was whether the unstable, lab-made elements were just as legit as their naturally occurring counterparts. “With former distinctions between ‘natural’ and ‘artificial’ rapidly vanishing in modern science, the answer seems to be yes.” Read the full story in New Atomic Charts Reveal Secrets of Radio-Elements.

Modern Alchemy: March, 1948

Ancient alchemists, including Isaac Newton, had one desperate ambition: transform a lesser material into precious gold. According to this 1948 article, U.S. “wizards” (also known as radiochemists) in Tennessee finally succeeded in manufacturing synthetic, radioactive gold using cyclotrons and atomic piles, though the treasure tended to disappear rapidly. PopSci also published Emilio Segre’s isotope chart, which resembled a “giant crossword puzzle.” The discovery of isotopes meant that familiar elements could have unexpected properties. Even “well-behaved elements like iron and sulphur may turn into something else while your back is turned!” Read the full story in U.S. Alchemists Make Gold.

Building Blocks of Science: November, 1946

PopSci readers have long enjoyed slicing up the magazine for some DIY entertainment. This 1946 issue includes a full-color periodic table that you can cut out and make into a “Courtines castle.” The accompanying article contains plenty of fun facts about rare earths, atomic weights and nuclear energy. Go ahead and grab the scissors and tape – if you don’t mind a periodic castle that’s missing elements 97-118. Read the full story in Building Blocks of Science.

All The Elements Found: December, 1931

Add this to the miles-long list of arrogant and inaccurate scientific announcements: In 1931, after the discovery of eka-iodine, PopSci declares that all the elements have been discovered. This snarky reader letter asks what the “poor” researchers will do with their time now. “I presume scientists will devote their spare time searching for new vitamins to complete the alphabet.” Anything to keep them from wasting effort “trying to prove that man came from a monkey.” Which egghead spit in his coffee? Read the full story in Pity the Poor Scientists with All the Elements Found.

Artist Paints Rhenium: September, 1931

Like Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man or Johannes Vermeer’s The Astronomer, this 1931 painting shows that the merging of art and science is a beautiful thing. Charles Bittinger painted the spectrum of the element rhenium, which had only been discovered a few years earlier in Germany. An element’s unique spectrum “is the band of colors produced when a small quantity of the element is heated to incandescence and its light broken up by a prism, giving a rainbowlike effect.” Read the full story in Artist Paints Spectrum.

American Discovers Illinium: June, 1926

In 1926, Professor B.S. Hopkins of the University of Illinois became the first American to discover a new chemical element! Or not. “Illinium,” named after his state, turned out to be contaminated didymium. The elusive element 61 was finally discovered in 1945 by scientists at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, who called it promethium, after the brave Titan who stole fire from the gods. P.S.: Good news! “Asthma Cured by Russian.” Read the full story in American Finds New Element.

Science Sees, Hears, Counts Atoms: April, 1924

PopSci received amazing news from Paris in 1924: “Madame Curie, famous as the discoverer of radium, had invented a machine more startling and filled with more dramatic possibilities than even the telescope that gave to man his first real understanding of the sublime wonders of the heavens”! Whew. This astounding machine makes it possible to hear and count the sounds produced as helium atoms are discharged from polonium. “A machine more amazing than that, the human mind is incapable of imagining.” Read the full story in Science Sees, Hears, Counts Atoms.

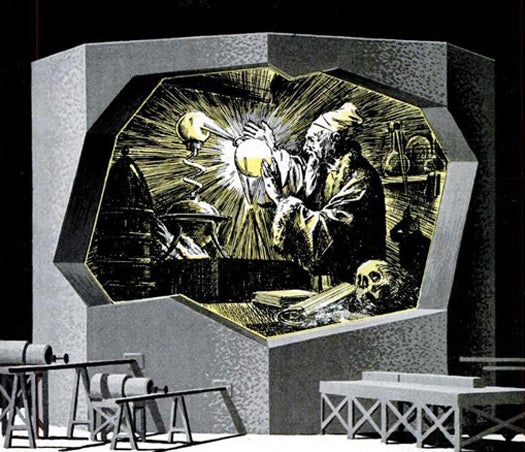

Science Explodes Atom: August, 1922

This half-terrifying, half-hilarious illustration from 1922 shows scientists at the University of Chicago accomplishing the “transmutation of elements,” or decomposing atoms of tungsten into helium and other elements. The ability to explode an atom offered scientists so much power that “transmuting lead into gold becomes of trivial significance.” In fact, with atomic energy, “a new industrial era can be pictured that makes the coal age seem medieval indeed.” Ah, yes, that primitive era when we used coal. Read the full story in Science, in Newest Feat, Explodes Atom.

The Periodic Law: June, 1901

Popular Science in 1901 published an early version of the periodic table that contained nearly as many question marks as it did official elements. Should sodium fall with copper, silver and gold, or lithium and potassium? And did oxygen belong in a group with chromium and molybdenum, or sulfur and selenium? Professor Jas. Lewis Howe of Washington and Lee University predicted that, although scientists knew very little about the chemical elements, Periodic Law would almost certainly become “the very foundation of chemistry,” with an influence just “as great as that of gravitation and evolution in their respective fields.” Read the full story in The Periodic Law .

On Elements: August, 1872

All the way back in 1872 (the year Popular Science was first published in the U.S.), William Odling explained the theory of elements. “The entire matter of the earth … so far as chemists are yet acquainted with it, is composed of some 63 different sorts of matter that are spoken of as elementary.” Elements are what they are because, “neither in the course of Nature or the processes of art, have they been observed to suffer decomposition.” Odling guessed, rightly, that science would continue to discover new elements, “possibly for centuries to come.” Read the full story in On the Discovery of the Elements.