Archive Gallery: Strange Sports of Tomorrow

Aquatic polo ponies, parachute sledding, balloon jumping, and more short-lived novelty sports from the early 20th century

If you’ve ever felt puzzled by the lack of similarities between polo and water polo, you’re not alone; clearly, one inventor from the 1930s thought that the latter could benefit from the inclusion of ponies. As silly as it looks, the idea wasn’t entirely unprecedented, nor was it original (two decades earlier, we covered an aquatic polo pony powered by a simple crank and gear). The era’s growing demand for novelty sports, aided by the growing sophistication of mechanical gear, sparked trends that involved everything from motorized water horses to rowboat-inspired race cars.

In retrospect, these new sports seem faddish at best, but at least we can appreciate how they reflect the most important innovations of the early 20th century. The Golden Age of Aviation inspired bubble-chasing, where daredevil pilots competed to pop helium balloons with their airplanes. Back on land, the commercialization of motorcycles and outboard motors gave us a least three new varieties of polo: motorcycle polo, pontoon polo, and of course, water-horse polo. Hobbyists borrowed elements from pre-established pastimes to create their own sports. For example, one French meteorologist adapted his interest in winter sports for parachute sledding (similar to modern-day snowkiting), while beach-going Europeans used human hamster wheels to run on water.

Unlike most of the developments we cover in these galleries, none of these sports left a lasting impact. Polo players still use real horses, parachute sledding remains an obscure diversion, and we’d be hard-pressed to see a sport like bubble chasing outside of a Mario Party minigame. But what’s history without its whimsical curios? In between all the depressions, wars and miserable whatnots of the past century, it’s nice to know that people made time to gaze at pilots diving after balloons.

Despite the similarity of their names, polo and water polo have almost nothing in common. We highlighted Antonio Alaj’s more literal interpretation of the latter, where he envisioned players riding mechanical “water-polo ponies” instead of actual horses.

At first glance, these ponies look more like carnival rides than sports equipment, but Alaj ensured that a fair bit of exercise went into operating these machines. Each horse was equipped with a system of cranks and gears. To maneuver the pony, players would pedal its twin propellers into action — not an easy feat while brandishing a mallet in one hand. “After all,” we wrote. “Polo without ponies isn’t polo at all.”

“How would you like to own your own hand-power jitney balloon — to spend your Saturday afternoons joy-riding in the sky, up a thousand feet or so, swinging beneath the round belly of a small gas-filled bag and traveling anywhere you can induce the playful breezes to take you?”

We’ve covered a lot of fantastic pastimes over the years, but we’d be hard-pressed to find a sentence more delightful than that one in our archives. Unlike manning hot air balloons, riding a “jumping sky jitney” didn’t require you to regulate the gas or unload the ballasts. By tugging a pulley, you’d whirl the propeller in charge of producing the proper five-pound upward and downward thrust. During its testing phase, the jumping balloon could fly for six hours at a time, jump 150 feet in one go, and maintain an altitude of 1000 feet for 40 minutes. If they were feeling courageous, ballooning students could even rope their craft together for group excursions.

In addition to revolutionizing travel, the golden age of aviation turned aeronautic stunts and sports into a national pastime. Nowadays, these spectacles are so unlikely that they might as well have come from a Mario Party minigame, but back in the 1920s, you could conceivably spend the afternoon watching pilots chase balloons with their airplanes. While aerial “bubble chasing” sounds silly in retrospect, audiences actually appreciated the opportunity to see pilots show off their maneuvers.

Other popular sports included parachute-racing, where contestants battled rogue air currents to land on the finish line; and balloon swimming, where players traversed the skies in “jumping balloons” (see previous slide). We predicted that future spectators would gather in “air beaches”, or city parks equipped with nets suspended from balloons to people drifting across the sky.

Based on the conception of balloon swimming, aquatic polo ponies, and now, land skiff racing, the convergence of land, sky and aquatic sports defined novelty sports in the 1920s and early ’30s. Like their namesake, these vehicles were used for races in England. Driving one was more or less like operating a rowing machine with wheels, which led us to name this sport as a worthy rival to cycling.

The mechanical ponies might have flopped, but people continued designing equipment that would allow polo players to enjoy their sport on the water. One unnamed boat builder from New Jersey caught our attention by attaching a bicycle-like framework and an outboard motor to a pontoon. This little craft could zip along at 25 miles an hour, and was steered by pushing a bar with one’s foot. One hand would be used to control the motor, while the other would swing the mallet.

All the futuristic sports outlined borrow elements from long-established pastimes, and hunting swordfish with a bow and arrow is no exception. Like their predecessors, these Long Island fishermen used arrows that were more harpoon-like than the ones typically used in archery. These days, swordfish aren’t especially favored in bowfishing, but enthusiasts continue the tradition by hunting carp, catfish and even alligator.

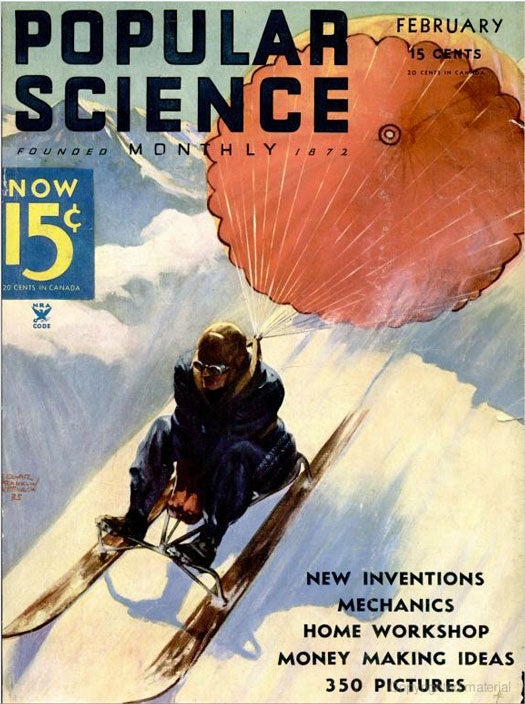

Few things make harsh winters more tolerable than winter sports. Using his expertise with wind patterns, French meteorologist Hubert Garrigue combined parachuting with sledding to create a sport so thrilling, we compared it to “plummet[ing] downward at express-train velocity.”

For safety’s sake, Garrigue fashioned the sled out of a pair of skis and a saddle. A self-opening parachute provided additional stability, allowing Garrigue to coast down 45-degree slopes without “hurtling to destruction.” After perfecting his technique, Garrigue expressed plans to make a parachute sled that would actually transport him up 55-degree slopes. Well, it beats taking the ski lift.

Like water polo, motorcycle polo shared little in common with its namesake. Players not only substituted motorbikes for horses, but they kicked the ball instead of hitting it with a mallet. If anything, the word “polo” afforded this game some credibility with new spectators who might not have known what to expect. Pragmatically speaking, motorcycle polo was more accessible to a broader range of people than regular polo, which is commonly associated with the upper class. Since motorcycles were more affordable, easier to ride, and simpler to maintain than specially-bred polo horses, we figured that it was only a matter of time before motorcycle polo became a mainstream sport.

For the most part, gameplay was unregulated; some leagues used standard motorcycles, while others used bikes specially modified for the game. As you can imagine, it made for an exhilarating sport: two teams of five would zoom around while attempting to score goals on either side of the field. Avoiding a nasty spill is one thing, but kicking a ball while weaving around enemy motorbikes requires coordination that even the best traditional polo players can’t always rival .

Instead of borrowing elements from pre-established sports, inventors of the water wheel drew inspiration from squirrel cages. The trend never became popular in America, but Europeans spent their holidays staging water wheel races along the shore.

If you think running like a hamster on a wheel looks simple, try actually doing so against the ocean’s current. This endeavor was especially challenging with wheels that could accommodate more than one person. Unless their endurance and speed were perfectly matched, one person was bound to run out of steam prematurely.

Water ponies made a brief comeback in 1938 when an unnamed inventor mountaineer a mechanical horse on a pontoon similar to the polo power boat from a few years back. Unfortunately, details on this invention are scarce, but we do know that the machine’s outboard motor saved riders the strain of pedaling.

Other strange inventions outlined in this feature include an electrical umpire for assisting baseball players with pitching, as well as a merry-go-round training machine for rowers.