Mike Massimino is hard to miss in a crowd — often because the crowd is surrounding him, eager to hear tales of his time in space. I was about to become one of them. I spotted Mike across the room of the Space Shuttle Pavilion at the Intrepid Museum in New York, standing underneath the left wing of the Space Shuttle Enterprise, taking photos with the people who had suddenly realized there was an actual astronaut in their midst.

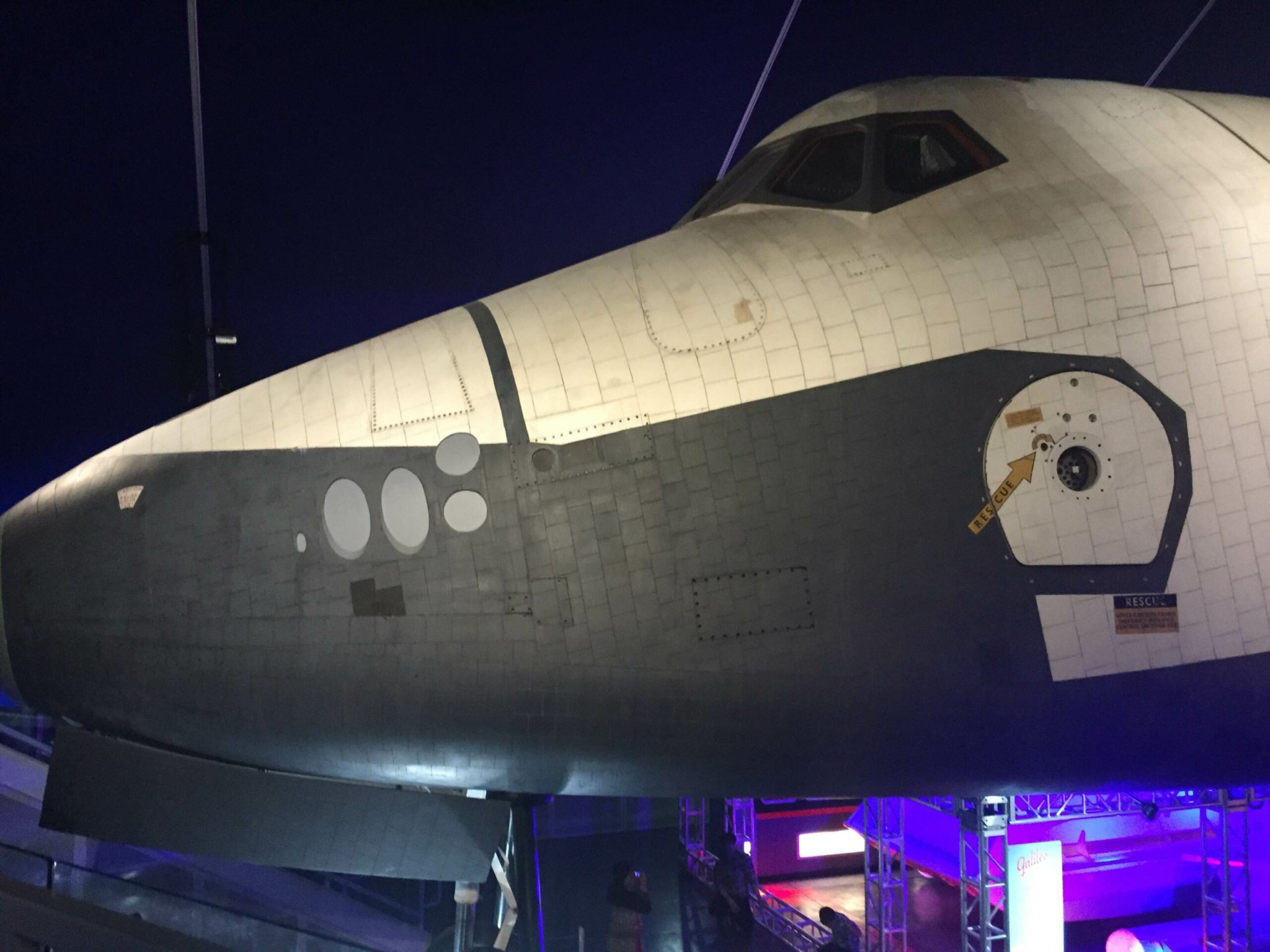

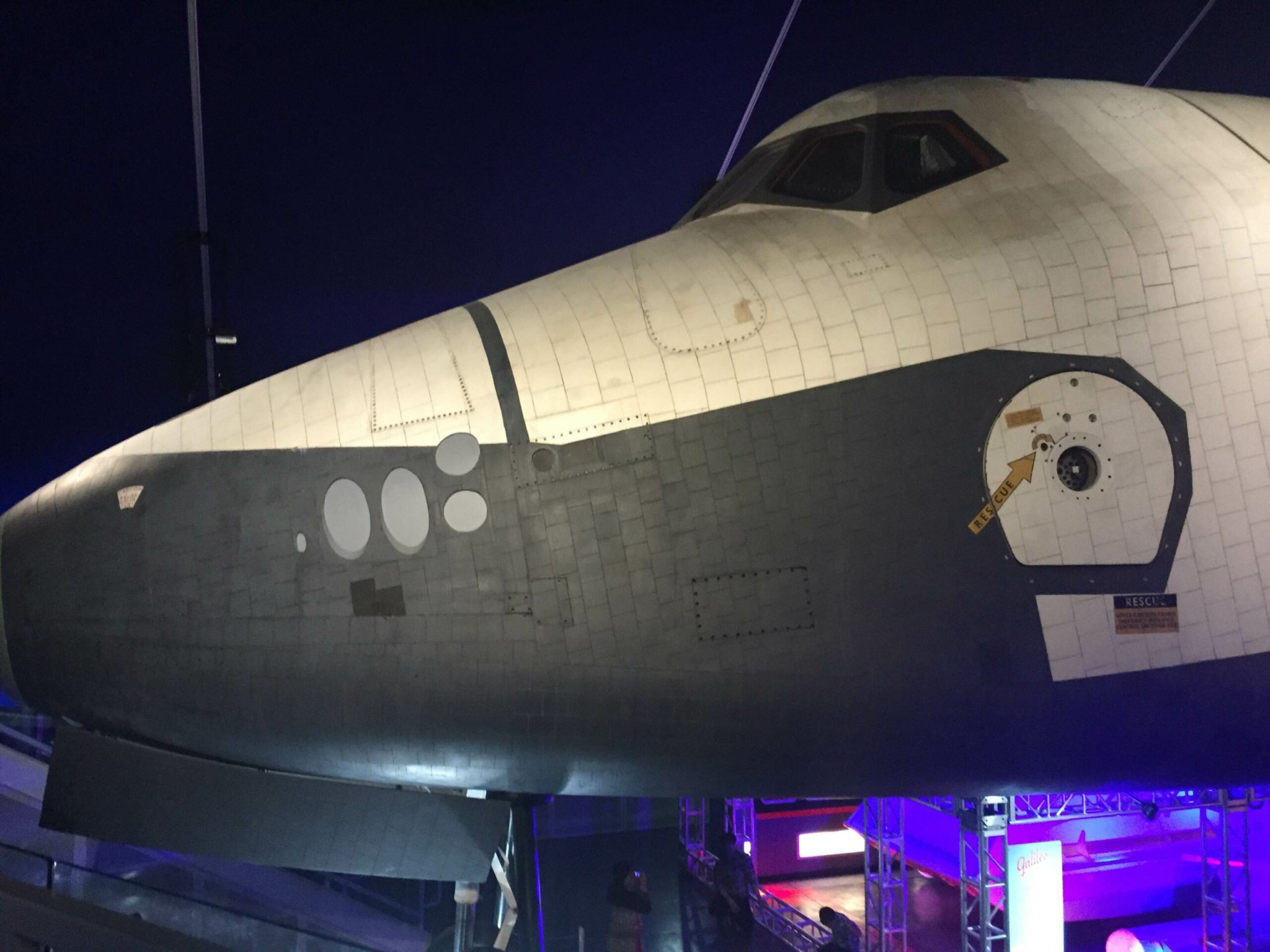

The Pavilion is a moody black, accented only by a few white lights highlighting the centerpiece of the room. The black belly of the Shuttle rests just a few feet above my head. If I had a chair to stand on, I could run my hands along the tiles heat shielding for this enormous spacecraft. The Enterprise, lovingly named after Star Trek‘s famous spaceship, never actually flew in space — it was the original proof of concept for the entire Shuttle program.

Mike has clocked over 30 hours in spacewalks and almost 600 hours in space. He retired from NASA a few years ago and now serves as Director of Space Programming for the Intrepid Air and Space Museum. He’s also a full-time professor of engineering at Columbia University, where he teaches a class called Introduction to Human Spaceflight, in which students learn extreme engineering, systems operations, and spacecraft design.

We stroll over to the nose of the craft. “See those metal latches on the bay doors? Those aren’t on the other shuttles, and those gray circular objects, those are where the reaction control system jets would be. The other shuttles have an engine valve there.”

His face still lights up when he looks at the Shuttle. “See how huge this thing is? You can fit an entire school bus in the loading bay, or something like the Hubble Space Telescope, or parts of the International Space Station.”

“I think this is the most spectacular spacecraft ever built,” he says. “And it’s probably going to be the coolest spaceship ever built for a while, because, I mean, look at this thing! The Soyuz down there looks like a dot,” he said pointing to the other end of the room.

As we approach the left wing of the Enterprise. Mike points out where NASA used parts of the wing to do research after the Columbia disaster in 2003. There are sections of the black insulating foam and the wing that look like they’ve been dismantled, messed with, and re-attached. “Doing this job is really dangerous. The last servicing flight to Hubble was the most dangerous Shuttle flight, because we only had a few extra days of life support. There were 17 days on the mission and there wasn’t any room for mistakes.”

Before he returns to work, I ask Mike what it was like being in space, the obligatory question when you meet someone who’s spent any time there at all.

“There’s really nothing like being there, looking at the Earth, the stars, the moon. That sensation is incredible. It gave me more of an appreciation for our planet; we really are lucky to live here. It’s a beautiful place; it’s also very fragile. I explain a lot of what it’s like in my book.”

I continue: How did you keep calm knowing you were just a few inches of glass away from a horrible death?

“It was crazy,” he says with another smile. “I wrote all of that down in my book.”